While the government has apologised for the treatment of Windrush citizens, Amber Rudd has resigned over her lack of knowledge about the Home Office’s removals targets. Christina Boswell provides some context to recent events. She concludes that although deportation targets are a problematic tool of performance measurement, the culture that exists within the government makes it very difficult to go without it.

While the government has apologised for the treatment of Windrush citizens, Amber Rudd has resigned over her lack of knowledge about the Home Office’s removals targets. Christina Boswell provides some context to recent events. She concludes that although deportation targets are a problematic tool of performance measurement, the culture that exists within the government makes it very difficult to go without it.

The recent scandal over removals targets has focused attention on the so-called ‘target culture’ that is rife in the Home Office. In fact, the organization has been driven by targets since the early years of the Blair administration. A series of ambitious ‘stretch’ targets were rolled out as part of the system of Public Service Agreements as early as 2000.

Initially, the targets were focused on making the asylum system more efficient. A target on the processing of asylum applications aimed to speed up the turnaround of decision-making on cases. While a further target on removals (yes, they go back that far), aimed to increase the number of rejected asylum seekers who were removed from the country. In this initial phase, the targets were largely about managing internal performance within the Home Office – what I’ve called the ‘disciplining’ function of targets. And they were not popular within the Home Office – officials talked of targets as a ‘necessary evil’ for securing resources from the Treasury.

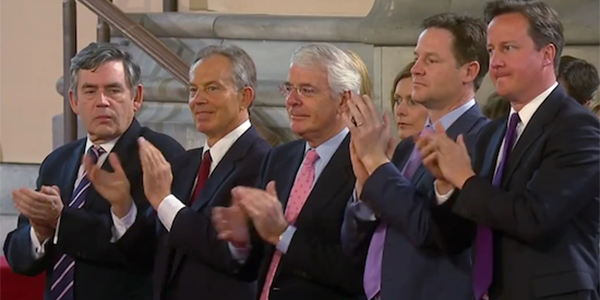

However, as asylum numbers continued to increase in the early 2000s, Tony Blair came under severe media and political pressure to show he was managing the problem. In February 2003 he announced a target of halving the number of people seeking asylum in the UK – a high-profile target, aimed at signalling the government’s commitment to tackle the issue. It was also a controversial target, as it implied deterring or preventing asylum-seekers from coming to the UK (rather than streamlining asylum procedures once they were here). And it was a hugely ambitious target, greeted with scepticism and derision by the press – the left objecting on ethical grounds, the right on grounds of its feasibility.

David Blunkett’s Home Office did go on to meet the target – though how far this was a result of changing conditions in countries of origin is still debated. However, its success received a lukewarm reception in the media, teaching the government that targets do not always serve well as tools of political communication.

Targets were again deployed in 2006, to address criticism of the Home Office in the wake of the ‘foreign national offenders’ scandal. This was the revelation that a hundred or so non-UK nationals had been released from prison after serving their sentence, without being considered by the Home Office for deportation. Removals were once again in the spotlight, with officials and ministers grilled by select committees over their failure to remove around 400-450,000 rejected asylum applicants. John Reid, newly instated as Home Secretary, introduced new targets to clear the asylum ‘backlog’, including an ambitious removals target.

In the second half of the 2000s, asylum figures were declining and the issue began to recede from media and political attention. Yet by then, the target culture had taken a firm grip on the Home Office and the UK Border Agency. As one former special advisor told me, it had ‘morphed into a more technocratic approach’, with a very complicated architecture’.

As these targets became increasingly complex and technical, they began to lose their purpose as tools of political communication – or ‘signaling’ function – becoming more about internal organization. Indeed, they became a thoroughly normal tool of Home Office management. One senior official told me they had tried to do without targets for asylum processing, but quickly reintroduced them as they had lost they ‘didn’t know what success looked like’.

By the end of the decade, targets were falling into disrepute. They were criticised as clunky, distorting and simplifying; they encouraged gaming, and their centralising tendency stifled initiative. The Conservatives and their Lib Dem coalition partners vowed to eschew targets – especially as a signalling device.

Of course, there was one prominent exception: the net migration target, announced by David Cameron in early 2010. This target, as is well-known, has been a ruthless driver of immigration policy, affecting all aspects of immigration policy that might have a bearing on the numbers admitted, as well as those leaving the UK. Thus it has affected policies on family migration, foreign students and labour migration, as well as, of course, influencing the decision to leave the EU.

It was natural that the net migration goal would be codified as a set of more specific targets – the Home Office’s go-to tool for performance management. And also to be expected that the targets would extend to implementation of the ‘hostile environment’ – Theresa May’s policy of enforcing immigration controls through outsourcing checks to a range of service providers, including employers, landlords, banks, education and health providers.

For me, the surprise is more in the way the media and parliamentary system has reacted to target-gate. We have had almost two decades of opposition parties, select communities and the media grilling governments on their failure to meet removals targets. This criticism has now been turned on its head: the fault lies in setting such clunky and unethical targets in the first place – not in the failure to meet them.

This is a welcome development, casting the spotlight as it does on the distorting effects of Home Office targets. It implies that politicians may in the future be more cautious about their use of targets. Unfortunately, though, I suspect that targets will continue to drive internal performance systems within the Home Office. Once you’re hooked on this tool of performance measurement, it proves very difficult to go without it.

______

Note: You can read more about the target culture in UK government in Christina’s new book; more information on the ESRC project underpinning the research is available here; and a blog summarising the project findings is available here.

Christina Boswell is Professor of Politics at the University of Edinburgh.

Christina Boswell is Professor of Politics at the University of Edinburgh.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Featured image credit: Pixabay (Public Domain).

Thanks for your feedback Christine. You specialise in the Home Office, whilst I worked for the FCO, but I am pretty sure that the experience was the same in both Departments. In, I think, 1985/6 zealous politicians introduced Management by Objectives to make the Civil Service (CS) more “efficient” and “responsive”. This US corporate management tool was brought in to shake-up what the Thatcher Government saw as the old-fashioned, out of date, stuffy and obstructive CS. (Perhaps a reaction to Yes Minister?). In the early days Departments sometimes demurred, indicating that such and such a practice was unsuitable to an organisation lacking the profit motive. But resistance was futile as Ministers deployed their own Doomsday Weapon – HM Treasury. Departments were informed that funding depended on the production of evidence that Ministries were meeting their objectives and/or targets and Treasury teams followed up on the ground. The CS may well have sharpened up its act initially but the result was – and I am told still is – that an increasing part of each Department’s and individual’s work was devoted to self-justification and navel gazing. As Deputy Head of Mission (DHM) in a medium Embassy in the early 90s I remember being told that if more than 20% of my job was administration then something was wrong. Major adopted the Thatcher approach and to our dismay the Blair Government became an enthusiastic convert. the result was that ten years later almost 70% of a similar job was devoted to administration, reducing considerably the amount of time available for what had been the priority, political reporting. That figure is even more now as confirmed to me by a former colleague. You expressed the wish that politicians “….may be more cautious in their use of targets” – if only. Nowadays Governments and Opposition are consumed with statistics which they trot out endlessly and every policy has to have a target. Getting them off targets will be harder than getting a junkie off heroin.

The rationale behind targets in this instance is purest folly. If there are x illegal immigrants in the country, x should be the target for deportation. After all, if – say – a local police station with 39 burglaries were set a target of bringing 50 burglars to book, or 30, what sense would that make?

The number of illegal immigrants being unknown doesn’t make arbitrary targets any more acceptable. Individuals should be identified and dealt with as they are identified. Set targets and officials will scrabble for the low-hanging fruit, Windrush being an example, just to hit them. Windrush was a result of people being in plain sight and so an easy option to up the figures. Truly illegal immigrants and more pernicious individuals require considerably more resources to detect and so are neglected. Quantity over quality.

Over and above all of this is the question as to why immigrants are such a big issue anyway. The background political chatter is now firmly set on the idea that immigrants are bad news, a populist notion based on ignorance which politicians should be working hard to dispel, not foster. Rivers of blood may be hyperbole, but recent increases in racial attacks are rivulets politicians should be damming, not dredging so they flow more easily.

There should only be one target for illegal migrants and that is 100% repatriation after all the clue is in the world, illegal. They have no right to be here.

Long ago I was told by a Colonel who had served with Skinner’s Horse during WW2 and was one of the world’s leading polo players, who knew a bit about targets, that if you gave any civil servant a target to hit he (in those days) would be bound to miss it by a mile.

An excellent piece but perhaps the history needs to be adjusted. I was a civil servant in the 1980s when the Thatcher Government, and in particular Lord Heseltine, decided that civil servants needed the discipline of the market place. They introduced management techniques such as Management by Objectives, which first spelt out the use of targets as a tool of government although the Civil Service culture and structure was not wholly suited to techniques used by profit seeking commercial companies

A second point worth underlining is that politicians are woefully incapable of understanding the effect of their pronouncements on the Civil Service. It is one thing for a politician to bemoan e.g. the backlog in asylum seekers, another for them to supply the resources to tackle the problem. Politicians think that by identifying a problem and wishing it to be tackled it will be solved without recruiting the staff necessary for implementation.

Thanks for this very helpful comment, Leslie. I was aware of the emergence of performance measurement under the Thatcher administration – but my research on the Home Office really starts with the Blair administration in 1997. I’d be fascinating to hear more about your time there.

I agree with your point about political criticism of the Home Office – indeed, I discuss this at length in my new book, especially in relation to Select Committee scrutiny of the HO. I hope you get a chance to read it, I’d be pleased to hear your comments!

You specialise in the Home Office, whilst I worked for the FCO, but I am pretty sure that the experience was the same in both Departments. In, I think, 1985/6 zealous politicians introduced Management by Objectives to make the Civil Service (CS) more “efficient” and “responsive”. This US corporate management tool was brought in to shake-up what the Thatcher Government saw as the old-fashioned, out of date, stuffy and obstructive CS. (Perhaps a reaction to Yes Minister?). In the early days Departments sometimes demurred, indicating that such and such a practice was unsuitable to an organisation lacking the profit motive. But resistance was futile as Ministers deployed their own Doomsday Weapon – HM Treasury. Departments were informed that funding depended on the production of evidence that Ministries were meeting their objectives and/or targets and Treasury teams followed up on the ground. The CS may well have sharpened up its act initially but the result was – and I am told still is – that an increasing part of each Department’s and individual’s work was devoted to self-justification and navel gazing. As Deputy Head of Mission in a medium sized Embassy in the early 90s I remember being told that if more than 15-20% of my time was taken up with administration then something was wrong. Sadly the Blair Government became an enthusiastic convert, and ten years later almost 70% of a similar job was devoted to administration, reducing considerably the amount of time for e.g. political reporting. That percentage is even higher now as confirmed to me by a former colleague. You expressed the wish that politicians “….may be more cautious in their use of targets” – if only. Nowadays Governments and Opposition are consumed with statistics and targets which they trot out endlessly on political programmes. Getting them off targets will be harder than getting a junkie off heroin.

“Getting them off targets will be harder than getting a junkie off heroin.”

We can try.

“I must stress that this statement contains only my preliminary observations, and highlights key issues without purporting to be a comprehensive summary of my findings. I will submit my final report to the June 2019 session of the United Nations Human Rights Council, and will continue to accept submissions until November 2018.”

End of Mission Statement of the Special Rapporteur on Contemporary Forms of Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia and Related Intolerance at the Conclusion of Her Mission to the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland

E Tendayi Achiume