Paul Whiteley and Harold Clarke explain recent changes in the patterns of support for Scottish independence. On the one hand, the financial and mental health implications of the pandemic have increased support for independence, as people want things to change. On the other hand, a number of recent developments have led to an upsurge in Britons thinking that the UK was right to leave the EU, which in turn helps to explain the loss of support for independence.

Paul Whiteley and Harold Clarke explain recent changes in the patterns of support for Scottish independence. On the one hand, the financial and mental health implications of the pandemic have increased support for independence, as people want things to change. On the other hand, a number of recent developments have led to an upsurge in Britons thinking that the UK was right to leave the EU, which in turn helps to explain the loss of support for independence.

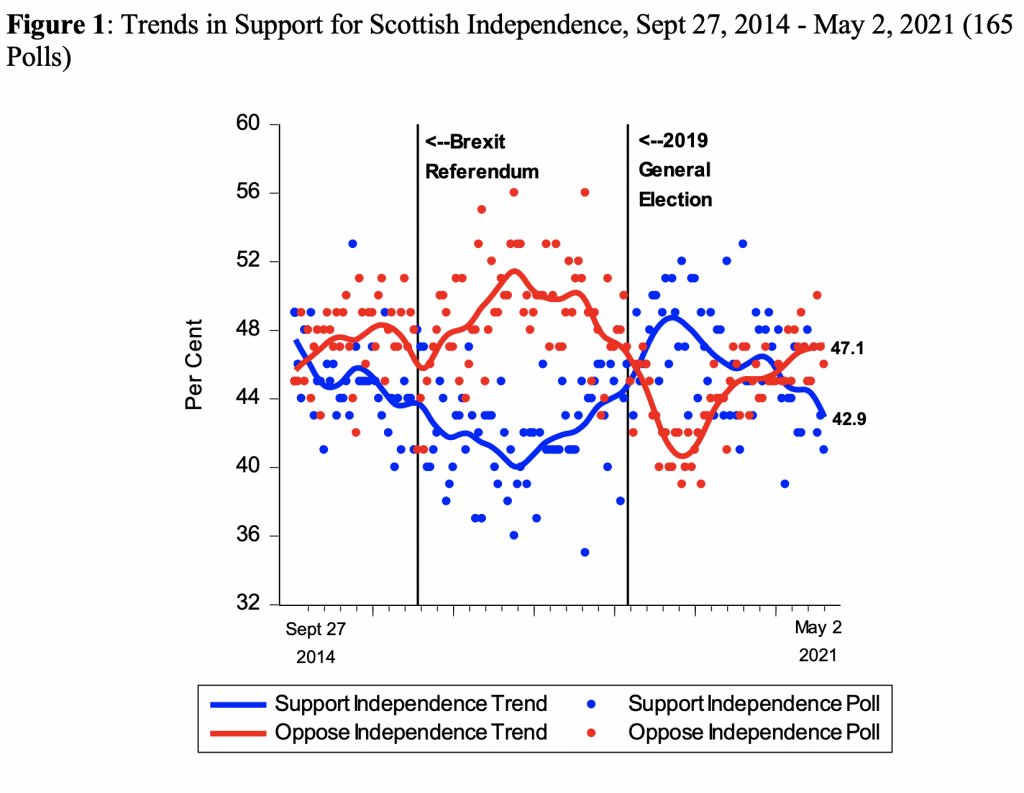

After a growth in support for Scottish Independence in the polls over the last year, attitudes to the issue in Scotland are now reverting to the pattern observed since the 2014 independence referendum (Figure 1). This is a relatively small but significant lead for those who reject independence. Figure 1 also illustrates that the striking characteristic of the polling evidence on this issue is the volatility in opinions over time. This is similar to the volatility in attitudes in the run-up to the 2016 referendum on EU membership. As we argued in our recent book on Brexit, this made the outcome of the referendum largely dependent on timing. Had it taken place, for example, on the same day as the 2015 general election it is highly likely that Remain would have won.

Data available here.

It is noteworthy that the surge in support for Scottish independence coincided with the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in January 2020. Pro-independence vote intentions reached a high- water mark of 52% in early October 2020 in an IPSOS-MORI poll. However, as Figure 1 shows, support for independence has trended downward significantly in recent months. For example, a Savanta-Comres poll conducted in mid-May indicates 43% are in favour and 47% are opposed (with 8% ‘don’t knows’).

Taken together, the poll numbers hint at a fairly straightforward explanation of attitudes to independence among Scots. When times are bad, they tend to support independence, and when times improve they are more inclined to oppose it. This is the same pattern that occurs in UK general elections – when the economy is doing well, the governing party tends to win; When the economy is doing badly the governing party is likely to be thrown out as disgruntled voters seek to relieve their misery.

In March 2021, a national survey of the British electorate conducted by DeltaPoll, consisting of more than 3000 respondents, throws interesting light on this idea. Respondents were asked: Have you had financial problems because of the Covid-19 pandemic? The possible responses were: ‘had serious financial problems’, ‘had minor financial problems’, and ‘had no financial problems’.

Source: March 2021 Essex-UTD national survey

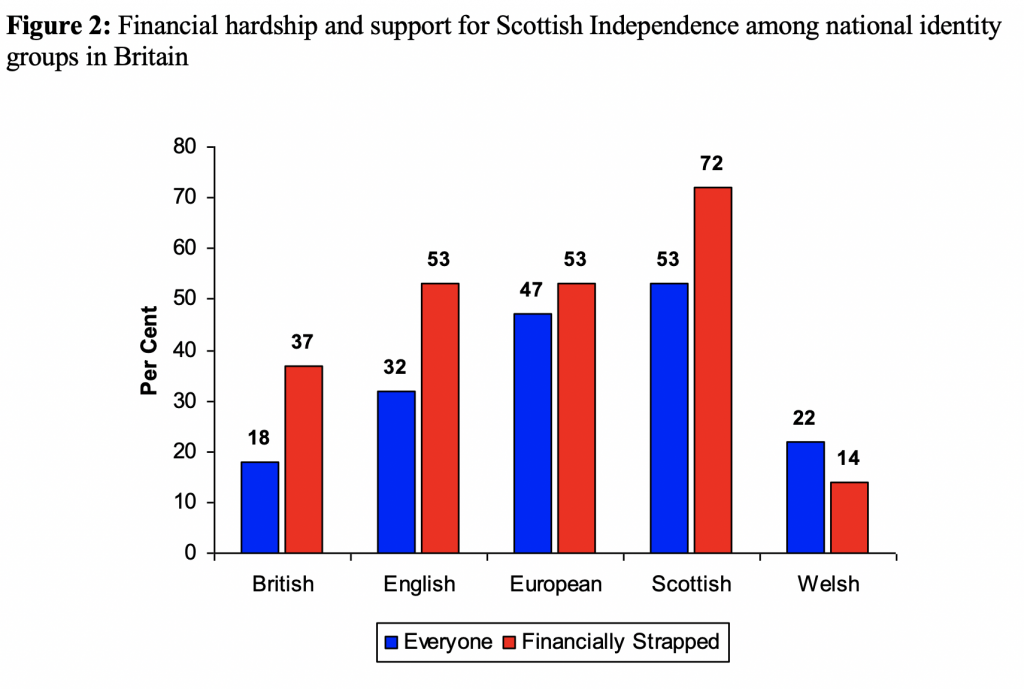

In an earlier article we looked at the relationship between national identities and attitudes to Scottish independence using data from this survey. In Figure 2, the blue columns show support for Scottish Independence in each of these identity groups. The red columns show the same thing, but only for those who reported having serious financial problems during the pandemic.

It is striking that support for Scottish independence increased in all groups reporting serious financial problems, with the sole exception of the Welsh identifiers. Support for independence soared among the Scots but also among the English identifiers who indicated that they were financially strapped. Clearly, financial adversity creates a desire for change for almost everyone. A large majority of Scots in this group want independence and a sizable majority of the English are happy to oblige them. The only holdouts are the British and Welsh identifiers.

It is also clear that changes in support for Scottish independence are not just a matter of financial hardship. The lockdown restrictions during the pandemic created mental health problems for many people. Another question in our survey asked: ‘Have you had any emotional problems like anxiety, depression or suicidal thoughts because of the COVID-19 pandemic?’ Possible responses were: ‘had serious emotional problems’, ‘had minor emotional problems’, and ‘had no emotional problems’

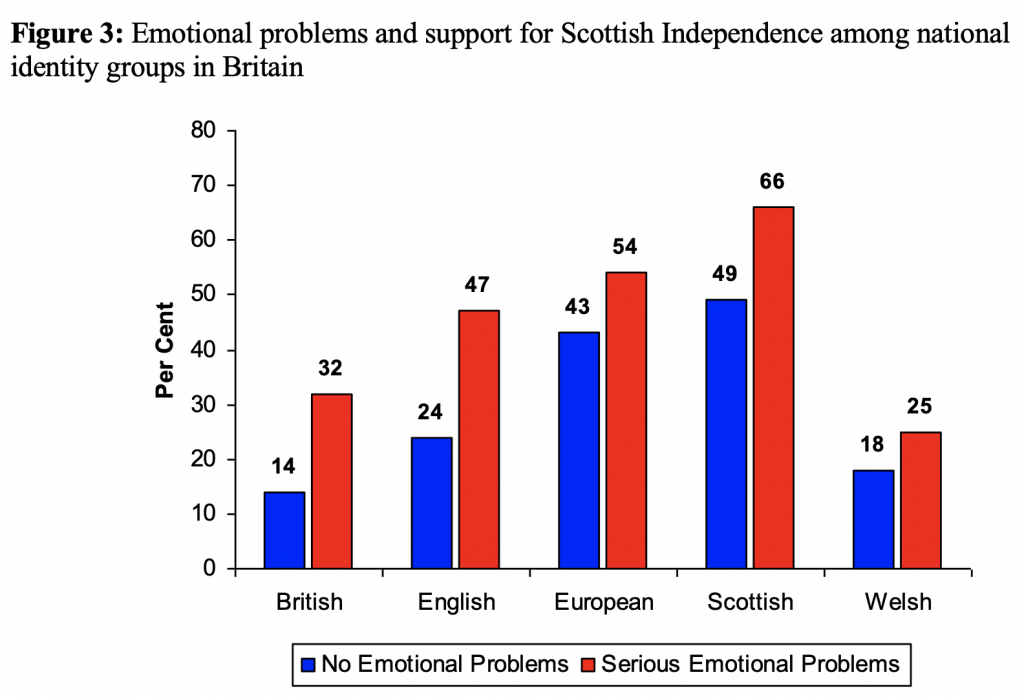

Figure 3 reports support for Scottish independence among respondents in the ‘serious emotional problems’ and ‘no emotional problems’ groups, classified by their respective national identities.

Source: March 2021 Essex-UTD national survey

The results are very similar to those in Figure 2. People who have experienced emotional problems in the pandemic want things to change and tend to think that Scottish Independence might improve things.

An additional factor is that there is a strong correlation (+0.55) between favouring independence for Scotland and believing that the UK was wrong to leave the European Union. This is evident in a time series analysis of the polling data over the period 2016 to 2020. But the failure of the EU to organise an effective vaccine programme, threats by the European Commission President Ursula Von Der Leyen to withhold vaccine supplies from Britain, and the fraught negotiations over trade have soured relations. This has led to an upsurge in Britons thinking that the UK was right to leave the EU, which in turn helps to explain the loss of support for independence in Scotland.

What are the implications of these survey results for the SNP’s strategy for achieving independence? The party has to get permission to hold a new referendum from Westminster and then go on to win it. A Catalonian-style declaration of independence is likely to end badly, with a boycott of an unofficial referendum by opponents, not to mention a legal challenge to its validity. This means that the SNP has to try to persuade the English and British identifiers that independence is a good idea, a strategy it has ignored in the past.

A second point is that the party is most likely to win a second referendum and independence if it is in the context of a significant economic recession following the pandemic. Currently, the Bank of England is talking up the expectation of a V-shaped response to the pandemic, that is, an economic crash followed by a rapid recovery. The Bank’s forecast is for a very rapid growth rate of 7.1% by the second quarter of next year.

However, extensive research on the economic effects of large-scale shocks reaches much more pessimistic conclusions. In a study which looked at 190 countries over a period of more than 40 years, two IMF economists show that large-scale shocks can produce losses of economic output that last a very long time. They conclude: ‘Using panel data for a large number of countries, we find that economic contractions are not followed by offsetting fast recoveries. Trend output lost is not regained, on average’.

The implications are clear: the road to Scottish independence will involve the SNP wooing not just Scottish, but also English and British identifiers. Doing so is most likely to be successful in the context of an economic recession. The prospects for such a downturn occurring in the foreseeable future are largely unknown. Economic forecasts have often proven wrong in the past and what will happen in the short- and medium-term in the wake of the massive, global dislocations occasioned by the pandemic is very much a matter of conjecture. If good times return, support for Scottish independence is likely to recede.

_______________________

About the Authors

Paul Whiteley is Professor in the Department of Government at the University of Essex.

Paul Whiteley is Professor in the Department of Government at the University of Essex.

Harold Clarke is Professor in the School of Economic, Political and Policy Sciences at the University of Texas at Dallas.

Harold Clarke is Professor in the School of Economic, Political and Policy Sciences at the University of Texas at Dallas.