The latest Labour controversy, stemming from the newest rule regulating leadership candidates’ tools for communication, merely illustrates how Corbyn’s leadership has used a language of democratisation to consolidate their faction’s position, write Zac Greene and Lauren Toner.

In late January, Labour restricted candidates’ use of party data to contact members during the leadership campaign. Although restrictions constrain candidates, non-party organisations such as Momentum retain the ability to contact their own membership, much of which overlaps with that of the party. This likely benefits the current leadership’s preferred successor, Rebecca Long-Bailey whom Momentum publicly backs. So, while the move appears to empower the rank-and-file by reducing the asymmetric information available to members of parliament, in practice it reinforces the concentration of power in the current leadership’s faction via a non-party organisation.

The reform is consistent in tone and practice with recent trends in the party’s ‘for the many, not the few’ tendency towards member participation. Jeremy Corbyn has notoriously relied on grassroots support in both his leadership campaigns and rallied this around policies that received backlash from backbenchers: the 2015 campaign saw Corbyn pledge to give members greater influence over new policy; and in the 2017 leadership challenge he pledged that party members, not the leadership, should choose the next shadow cabinet.

These reforms represent an international shift towards greater membership inclusivity. For example, Bernie Sanders credited increasing support during his 2016 presidential bid to the grassroots-inspired campaign while his supporters railed against the (modest) requirement to declare a partisan affiliation in closed primary states before participating. First-time politicians such as Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez further attribute their success to this approach.

Popular narratives conceive of inclusive leadership elections as if greater ‘internal democracy’ is normatively good. The argument goes that increased internal democracy invites a broader range of citizens to participate, increasing that way external legitimacy, membership numbers, and supporters’ satisfaction with the party and democracy more broadly. Although allowing the public to have a say in such consequential decisions –in the present case electing the leader of the Opposition and potential future Prime Minister – presumably increases the average citizen’s opportunities to influence party politics, less is known about the implications of these measures for political outcomes. Studies of electoral institutions demonstrate that the rules regulating elections and party reforms disproportionately benefit some groups at the expense of others.

Barring an official open primary as in many US states, the Labour party holds an extremely inclusive leadership selection process. Yet when party leadership contests include a wider pool of voters, more candidates enter the race, although most fail to receive much support. In such elections, voters identify front-runners in the early stages of the campaign and then reduce their choices to those most likely to win. Candidates also tend to drop out before the final ballot is cast. Thus, internal democratisation appears normatively positive at face value, but the benefits for party members and citizens more generally prove illusory, not to mention the unintended consequences for the strategies candidates develop in the process.

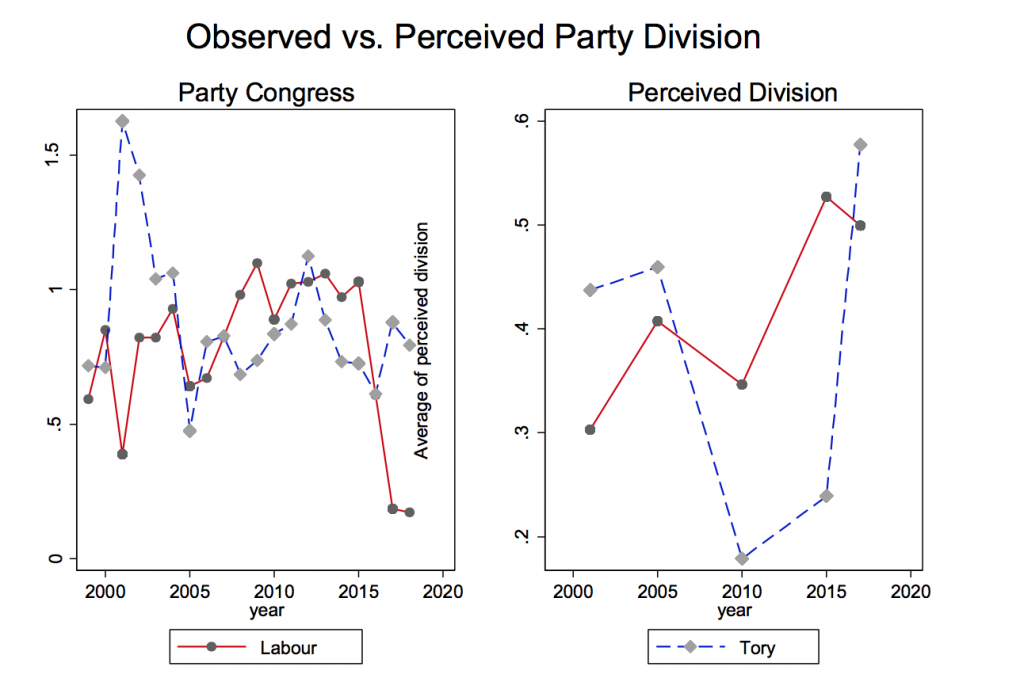

We present further evidence that recent intra-party reforms complicated Labour’s electoral strategies. Although Corbyn promoted internal democracy, evidence shows that the party sought to manage intra-party divisions by limiting who could participate in major public meetings. Figure 1 shows a comparison of the variation in speakers’ positions measured from their speeches at party conferences (see here for the approach) with the percentage of voters perceiving the party as divided from the British Election Study. While perceptions of disagreement within Labour significantly increased from 2015 when Corbyn took control of the party, disagreements at these meetings decreased dramatically throughout his tenure, reflecting attempts to exclude internal opposition. Yet although dissenting opinions were excluded, voters seemed to take note of this manipulation and of the fact that Labour members might not have been given the voice they were promised after all.

This pattern continued at the 2019 conference where the list of speakers frequently left out key dissenting voices (e.g. Tom Watson’s last minute exclusion). Thus, while the consensus-based policy style promised by Corbyn should encourage an increased diversity of issues for debate, and the level of detail at which policies are discussed, this contrasts with the actual legacy of Corbyn’s leadership. Increasing the pool of those voting in the election, limiting factions’ access to public deliberative forums, and placing constraints on candidates that disproportionately benefit the outgoing leader’s preferred candidate, mark an exclusionary, adversarial set of practices that may increase the likelihood that voters perceive serious division within the party.

This pattern continued at the 2019 conference where the list of speakers frequently left out key dissenting voices (e.g. Tom Watson’s last minute exclusion). Thus, while the consensus-based policy style promised by Corbyn should encourage an increased diversity of issues for debate, and the level of detail at which policies are discussed, this contrasts with the actual legacy of Corbyn’s leadership. Increasing the pool of those voting in the election, limiting factions’ access to public deliberative forums, and placing constraints on candidates that disproportionately benefit the outgoing leader’s preferred candidate, mark an exclusionary, adversarial set of practices that may increase the likelihood that voters perceive serious division within the party.

The recent restriction on parliamentarians’ use of data is just the latest example of how changes that can be framed as an attempt to increase internal democracy can actually undermine the party’s organisation and membership, risking the party’s ideological coherence and long-term stability. While the 2020 leadership contest represents one of the most inclusive decisions for the average citizen a party can make, in practice the process appears to be selective: grassroots empowerment applies to supporters that mirror the leadership’s views.

By making the leadership election more similar to a general election campaign while also pursuing a number of exclusionary behaviours, recent rule changes have rendered the outcome in the eyes of intra-party groups as ‘winner-take-all’ and have increased the likelihood that members air differences publicly to impact internal debates. Given the ongoing controversy surrounding these changes, it is unsurprising then that voters note this inability to compromise and draw implications for the party’s ability to competently govern.

_________________

Zac Greene is Senior Lecturer and Chancellor’s Fellow in the School of Government and Public Policy at the University of Strathclyde.

Lauren Toner is an ESRC-funded PhD student at the University of Strathclyde.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.