The Welfare Reform and Work Bill, currently going through the House of Lords, proposes to remove all income and material deprivation measures from the Child Poverty Act. By doing so, the government is acting against the advice of 99 per cent of respondents to its own consultation on the matter, find Nick Roberts and Kitty Stewart.

The Welfare Reform and Work Bill, currently going through the House of Lords, proposes to remove all income and material deprivation measures from the Child Poverty Act. By doing so, the government is acting against the advice of 99 per cent of respondents to its own consultation on the matter, find Nick Roberts and Kitty Stewart.

Set against high profile discussions of proposed changes to the tax credit system, another government reform with serious implications for low income families has received relatively little attention. Under proposals in the Welfare Reform and Work Bill, the current suite of income-based child poverty measures and targets in the Child Poverty Act 2010 are to be axed and replaced with new measures of worklessness and of educational attainment at age 16. In addition, duties and responsibilities on national and local government to reduce child poverty will be removed, and the Act itself will be retrospectively renamed the Life Chances Act 2010. The government has also announced that it will “develop a range of other measures and indicators of root causes of poverty, including family breakdown, debt and addiction.”

The existing Act contains four measures: relative income poverty (children living in households below 60 per cent of the national median); ‘absolute’ income poverty, calculated against a poverty line pegged to median income in 2010/11; a combined low income and material deprivation measure; and a measure of persistent poverty. These measures were chosen following extensive consultation and were designed to complement each other, with each capturing different aspects of poverty.

The Act was passed with cross-party support – although the Conservatives warned that they believed the measures to be “poor proxies for achieving the eradication of child poverty” and argued that they would focus on “tackling the causes rather than the symptoms of poverty”, naming these as worklessness, education, family breakdown and addiction. What is happening to the Child Poverty Act now, then, is perhaps no more or less than what was expected.

And yet the planned changes stand in direct conflict with the vast body of expertise and opinion on the definition and measurement of child poverty. We know this because we have examined the responses to a consultation held in 2012-13 by the Coalition Government into precisely this topic. Measuring Child Poverty put forward the idea of a new multidimensional poverty measure that “will reflect the reality of growing up in poverty in the UK today and how this has an impact on outcomes in later life”, asking for views on a range of potential ‘dimensions’, including income, worklessness, unmanageable debt, poor housing, family stability, parental health, drug/alcohol addiction and the impact of attending a failing school.

The Department for Work and Pensions published a brief summary of the responses in 2014, but in light of the current proposals we decided to examine the responses themselves, to gauge the level of support for the current measures and for the role of income in poverty measurement. A Freedom of Information request gave us access to 230 of the 257 responses, submitted by academics, think tanks, local authorities, voluntary sector organisations, frontline services and individuals, between them pulling together many decades of experience in service delivery and research.

The following findings are based on our analysis of these responses and lead to an incontrovertible conclusion: There is very strong support for the existing measures, and near universal support for keeping income poverty and material deprivation at the heart of poverty measurement. We think this needs to be clear in public debate as the changes to the Child Poverty Act go through Parliament.

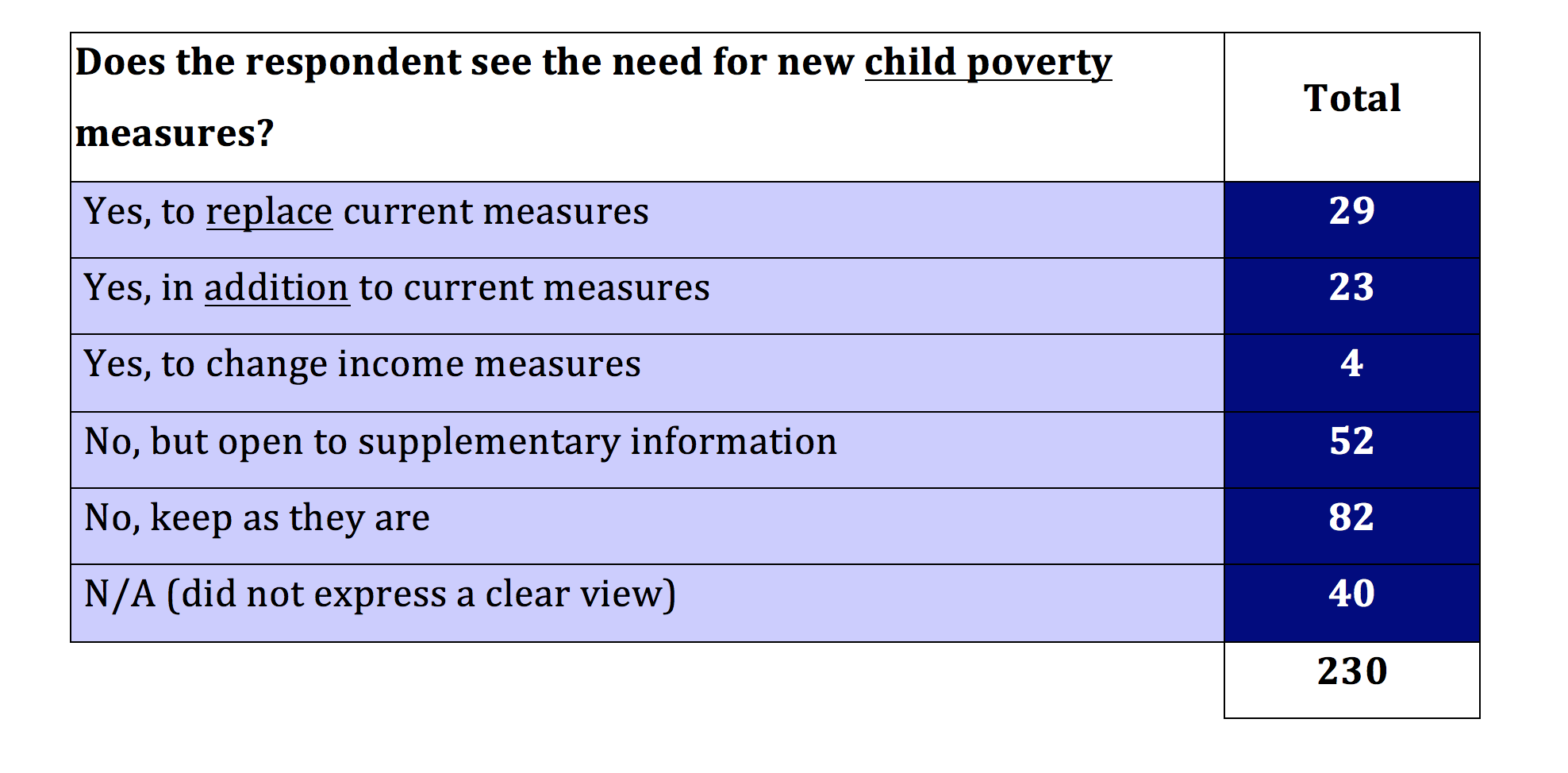

First, there is a very high level of support for the current Act. Although the consultation form itself made no reference to them, 82 responses specifically stated that they would like to keep the existing measures as they are and wanted no change, while a further 52 made it clear that they would only support indicators relating to additional dimensions if they were treated as supplementary information (relevant to wider child well-being or to children’s broader life chances) but not as measures of child poverty itself (see Table 1). A total of 56 respondents were open to new child poverty measures but for a significant share of these this was still only in addition to the full suite of current income-based measures. Only around 14 per cent of respondents wanted to change the measures themselves. Clearly, there is little appetite for change amongst those most concerned with child poverty.

Table 1

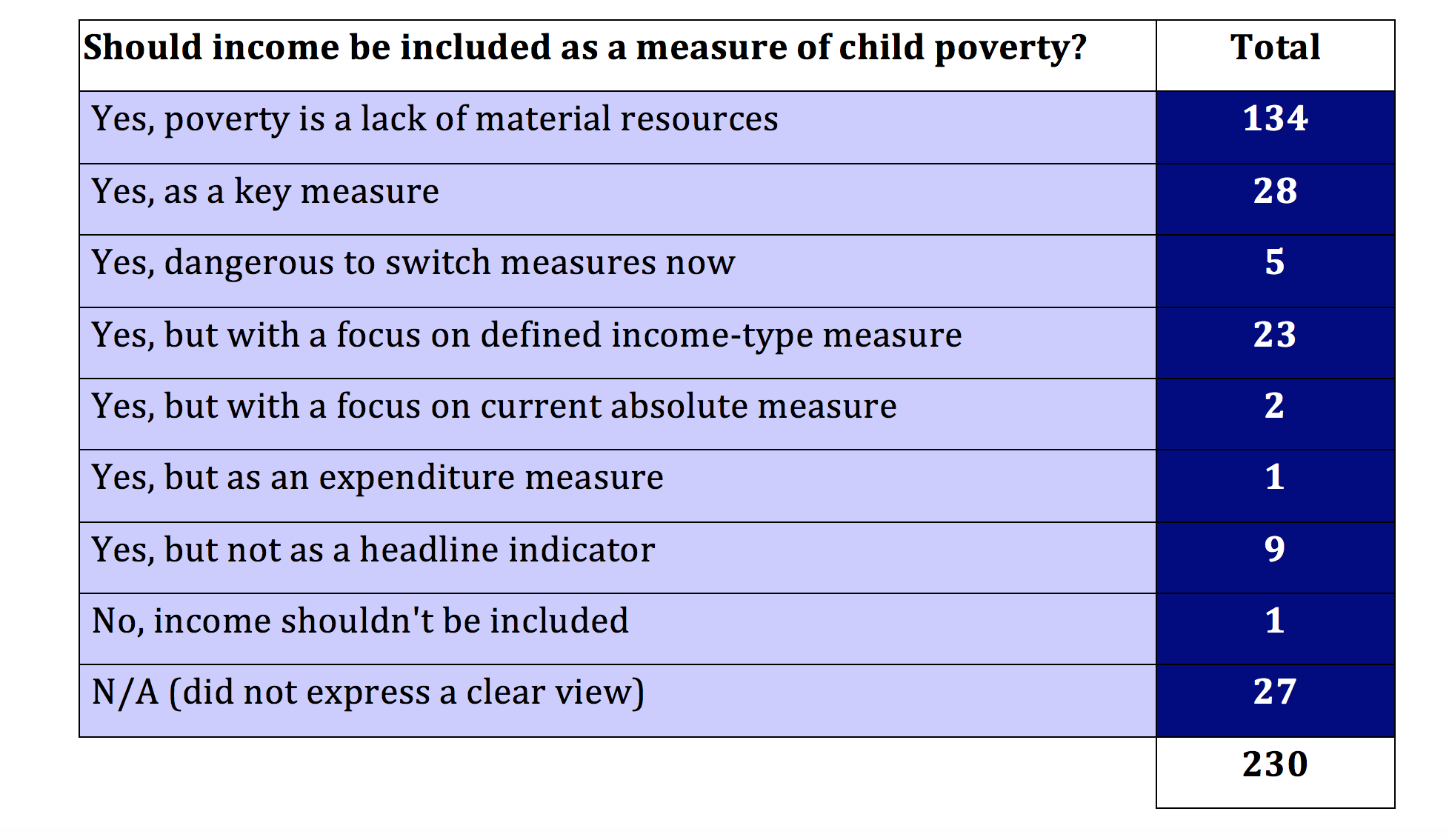

Second, there is near universal support for the inclusion of an income-based measure. Indeed, the message is stronger than that: as can be seen in Table 2, for the majority of respondents – 134 – child poverty is defined by a lack of material resources, with income, alongside material deprivation, the best way to measure this. In other words, for most respondents, income was not seen as one more ‘dimension’ amongst others, but as the very core of child poverty. This was true right across the sample, reiterated in responses from academics, local authorities, voluntary organisations and frontline services. In fact, of the 203 responses that referred to income in their response, only nine responses felt that income should be included as anything but a headline measure and only one, from a private individual, felt that income should not be included at all.

Table 2

Third, there is also very strong support for the concept of poverty as relative, and for continuing to track relative income measures, despite the consultation document highlighting that a relative measure can give a misleading picture when median income falls during a recession. Respondents repeatedly emphasised that the existing measures each have strengths and weaknesses and need to be considered together. A small number advocated switching to a poverty line based on a defined income level, feeling it made more intuitive sense and would be easier to explain to the public. However, even amongst this group, the majority still took a relative stance, with many mentioning the Joseph Rowntree Foundation’s ‘Minimum Income Standard’ measure. Only two or three argued for a more subsistence-type ‘absolute’ measure.

The fourth and final point relates to the new ‘dimensions’ proposed as replacement measures by the government. There was support for tracking indicators relating to some of these, in order to help understand their relationship with poverty. However, they are widely considered to be unsuitable as measures of child poverty itself, as many responses very clearly spelt out. Taking ‘worklessness’ as an example, whilst many respondents acknowledged that children living in households with no working adult are more likely to live in poverty, almost as many pointed out that the majority of children living below the poverty line in the UK today have at least one working parent. Others noted that paid work may not always be possible or in a family’s best interest, such as in households where a lone parent is caring for a very young or disabled child. If children in these households live in poverty it is because of low material resources, and the inadequacy of policies to address this, not because of the lack of paid work per se. As repeatedly highlighted in responses from across the full spectrum of contributors, it is a lack of material resources alone that is common to all in poverty and only to those in poverty. It is therefore only a lack of household resources, with income as the best proxy, that is suitable as a measure of child poverty.

This gets to the heart of criticisms of the government’s proposals. The dimensions that have been proposed can be understood as causes of poverty, like worklessness, or consequences of poverty, like educational attainment. They may also be considered important to wider child well-being, or to children’s development and life chances. But they are not poverty itself, as it is understood by the overwhelming majority of respondents to the consultation. In the eyes of this majority, the government’s amendments are not changing the child poverty measures, but bringing an end to the official measurement of child poverty in the UK.

Why does this matter? For one thing, it is disquieting to see the government acting in direct contradiction to such strong and unanimous expert opinion. More importantly though, it matters because this is not ‘just’ a question of measurement, but an indicator of government priorities – a point underlined by the removal of the requirement for national and local authorities to have (and to follow) a strategy for child poverty reduction. And this in turn matters because government policies can influence household income very directly – more so than they can perhaps any other variable, and certainly more easily than they can affect household worklessness or young people’s educational attainment. Recent discussion about the effects of proposed tax credit cuts provide one illustration of this. That the government is opting out of holding itself to account over measures that are widely understood to be of crucial importance to children’s lives, and that it has considerable power to do something about, is of serious concern. It is a development that can only be damaging to the interests and prospects of children in low-income households.

___

Note: the article represents the views of the author and not those of the British Politics and Policy blog nor of the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting.

___

Nick Roberts recently completed an MSc in Social Policy (Research) at the LSE

Nick Roberts recently completed an MSc in Social Policy (Research) at the LSE

Kitty Stewart is Associate Professor of Social Policy at the LSE and Research Associate at the Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion (CASE).

Kitty Stewart is Associate Professor of Social Policy at the LSE and Research Associate at the Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion (CASE).

Featured image credit: Paul Downey CC BY 2.0

It’s nowadays expected that the second adult in the household makes up for income deficit and is somehow responsible for poverty if not also in paid work!! Current policies assume that if there’s persistent family poverty it’s because couples aren’t working enough hours. Care responsibilities, which take time, are ignored. In any case the contribution of caregiving is worth billions to economy even if not included in GDP yet. The Govt needs to take responsibility instead of blaming ordinary people when the system is clearly not working.

Can anyone tell me why the FOI request the authors used to obtain details of the responses to the Gov consultation yielded access to only 230 responses rather than the full 257? Do the authors know who these excluded respondents were?

Apologies for the slow reply – I only just saw your question. I think it was just administrative error rather than conspiracy. We’ve been back to the DWP twice to try to fill in the gaps and now have 251 responses. There was nothing particularly different about the extra 21, seems they just got missed out of the photocoyping pile. Of the remaining six, four people/organisations requested that their response remain confidential so we can’t have those. Then there is one from a London council for which we have the cover sheet but not the content – again, seems like error and I’m chasing it up. Using the DWP’s summary figures of respondents the final one is from an individual and we might just have to leave that one out.

Congratulations. Excellent work that deserves to be shared widely.

Thank you for your work in this area and for highlighting a little known, but fundamental change to the definition of child poverty. It’s quite incredible if I wasn’t already alert to the kind of country this government is set on creating. It deserves a revolution of some kind, but most of the effects fall below the radar.

This kind of thing is done all the time in the USA. Poverty is seen not in terms of a temporary or more long term reduction in material resources…rather as a sign of an inner moral failing. Nothing will change their view point…that is what our lawmakers WANT to think. All social policy is grounded on this flawed premise. For example: The Kansas legislature decided that people on welfare must be mostly drug addicts. There is no evidence for this…still they instituted in my state (Kansas) an expensive drug testing program to ferret out the miscreants. Course there were very few drug positives (same result as in Florida). No matter…They rule by leap of faith…according to a world as they have envisioned it work.. “Facts” are just something you twist to fit into that preconceived reality. This view dovetails nicely with the utter disregard the US legislatures in general have towards the general population. Their election was financed by and for enrichment of the financial and other powerful multinational corporations.