Monica Langella and Alan Manning find that high unemployment in an area induces people to move away, and has an even stronger effect on the attractiveness of that area to potential movers. They also find that younger and better-educated individuals are less sensitive to distance and tend to move further away than other groups.

Monica Langella and Alan Manning find that high unemployment in an area induces people to move away, and has an even stronger effect on the attractiveness of that area to potential movers. They also find that younger and better-educated individuals are less sensitive to distance and tend to move further away than other groups.

Regional inequalities are strongly persistent in many countries and this can have both economic and political consequences: feeling ‘left behind’ by austerity policies may have had impact on recent electoral outcomes. One mechanism that could smooth out spatial economic differences is migration. For instance, moving to an area with better opportunities can increase the probability of having a job and improve one’s economic prospects. Then, areas with worse economic conditions should experience a decrease in population in favour of areas that start from a better economic situation. Looking at the UK case, data seem to confirm this. Neighbourhoods that had high unemployment in the 1980s tend to have bigger drops in population 40 years later, as Figure 1 shows.

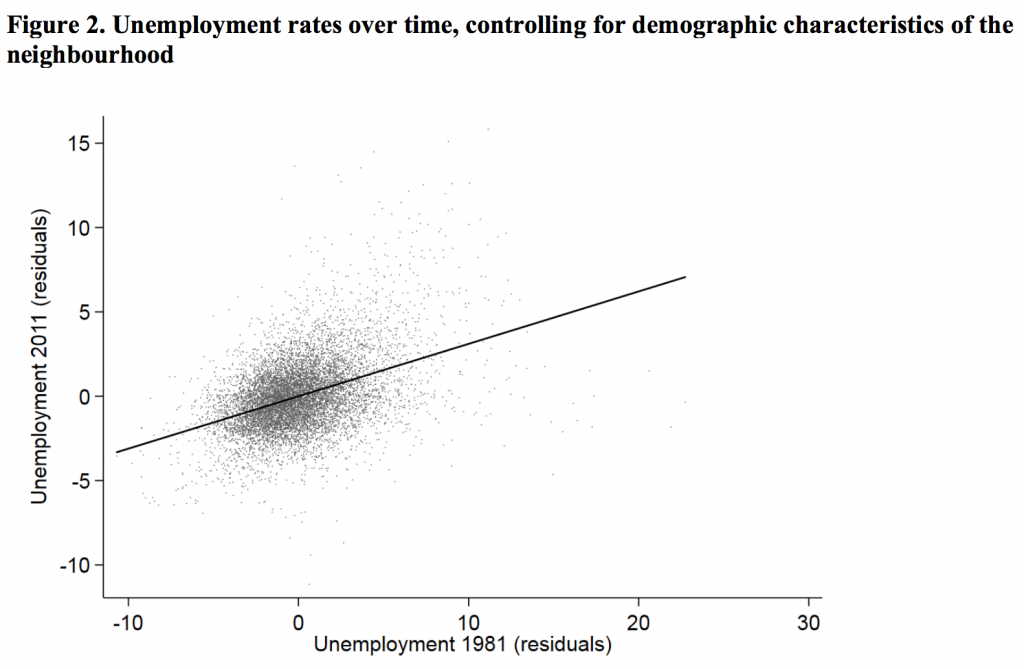

In the same line though, one should also expect that areas would converge over time in terms of economic performance, but that is not what Figure 2 suggests. In the UK, as in many other countries, spatial economic differences are quite persistent.

Note: the models include controls for age distribution, marriage rates, student presence, and education rates.

Note: the models include controls for age distribution, marriage rates, student presence, and education rates.

If populations respond to economic shocks, why is persistence in economic conditions still so strong? Others have shown that, although in the UK migration dynamics do respond to local economic shocks, they are not able to keep up with the speed of economic adjustments. Building from there, we study the dynamics of residential mobility to understand what can explain the slow adjustment. We do so by looking at very detailed data that records moves between census area statistics (CAS) wards – these are areas of approximately 5,000 people, and there are more than 10,000 such wards – both at the aggregate level and at the individual level.

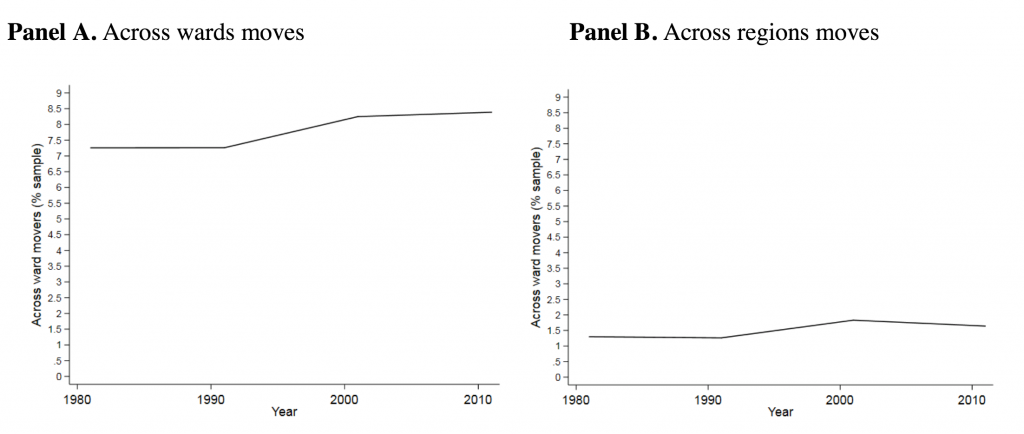

First, we look closely at the role of distance in explaining residential mobility. Most of residential mobility in the UK occurs within regions, as Figure 3 shows, so it is not surprising to find that the relationship between distance and mobility is very strong. For instance, estimating a distance cost function on a full ward-to-ward pair matrix of residential flows, we find that doubling the distance between two places makes the mobility drop by 73.5%.

Figure 3: Percentage of population who moved based on census data

Second, we study the impact of local unemployment on population inflows and outflows. We find that local unemployment negatively affects inflows and positively affects outflows, thus causing people to move away from areas of high unemployment and towards areas of lower unemployment. A 1% increase in unemployment in one area decreases the inflow from 1.5% to 4% in our instrumental variable models, while it increases outflow by about 1.6%.

Third, we use individual level data to study whether different groups of people have different reactions to economic conditions and whether their cost of distance is different. Understanding this is important because the view that migration tends to equalize economic opportunity is based on the idea that migration reduces competition for jobs in the areas left and increases it in the destination areas. Such a conclusion may not be justified if, for example, it was the best educated or the most ambitious who leave an area after a negative labour demand shock – this would alter the skill mix in a way that might worsen labour market prospects for those left behind. For example, recent work suggests that out-migration of young people is likely to have a negative effect on the settlement of new firms in the departure areas.

With this in mind, we look at heterogeneities both to distance and to economic opportunities, for inflows and outflows separately. We find that:

- younger people and people with higher levels of education tend to move further away, while people in social housing, people who are working, and people with children tend to choose closer destinations;

- married people are less likely to move to high unemployment areas, as are older people;

- non-white people are relatively more likely to choose more high unemployment areas, as are those in social housing;

- regarding outflows, women and people with children are less sensitive to the unemployment in the area, while for married people unemployment appears to matter more.

Overall, we spot some mechanisms that could explain why changes in population are not strong or fast enough to offset the persistence of economic shocks. Mobility is a local phenomenon. People who move do so within a few kilometres from the original location, so they are likely to remain under similar economic conditions. Even though they move locally, people tend to take into account local economic conditions, as unemployment causes both fewer people to move to a certain area and more people to move away from it. Moreover, different groups of people tend to have different dynamics of residential mobility, so it is difficult to assume that the people who leave and the ones that stay in the area are similar. This may have an impact on the potential that migration has in smoothing out special disparities.

__________

Note: the above draws on the authors’ paper for the LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance.

Monica Langella is Research Officer at the Centre for Economic Performance, LSE.

Monica Langella is Research Officer at the Centre for Economic Performance, LSE.

Alan Manning isProfessor of Economics at the LSE.

Alan Manning isProfessor of Economics at the LSE.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Featured image credit: Pixabay (Public Domain).