John Van Reenen was disappointed but not surprised by the UK’s vote to leave the EU. Whilst his own research predicts serious economic and political damage in the case of Brexit, he thought a Leave vote was a real possibility ever since David Cameron committed to a referendum in 2013. As he leaves the LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance, he gives his verdict on the campaigns, the media, politicians – and being a derided expert.

John Van Reenen was disappointed but not surprised by the UK’s vote to leave the EU. Whilst his own research predicts serious economic and political damage in the case of Brexit, he thought a Leave vote was a real possibility ever since David Cameron committed to a referendum in 2013. As he leaves the LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance, he gives his verdict on the campaigns, the media, politicians – and being a derided expert.

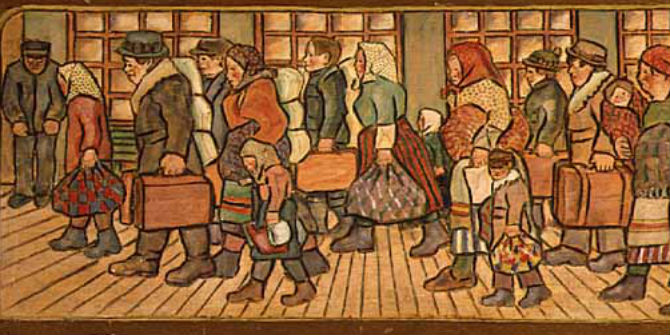

There are multiple reasons for the Brexit vote, but by far the most important one can be summarised in a single word: immigration. In the last few weeks before the vote, the Leave campaign was ruthless in focusing on our fears of foreigners. Sadly, with the exception of London, this has been shown time and time again to be a great vote winner all over the world.

The British people have suffered tremendously since the financial crisis. The real wages of the average person fell by about 10 per cent between 2007 and 2015. This is not about inequality – poor, middle and rich have all lost out. It has been the longest sustained fall in average pay since the Great Depression and it has made people very angry with the establishment – and rightly so. As LSE’s Professor Stephen Machin, the new Director of the Centre for Economic Performance has shown, the areas with the biggest falls in average wages were the places most likely to vote for Brexit.

These wage falls and poor job prospects have nothing to do with immigration and everything to do with the financial crisis and slow recovery. But because immigration tripled since 2004, lots of people know of a friend or family member going for a job and a European migrant getting it. So it is easy to point a finger at foreigners as the cause of labour market problems. This is the ‘lump of labour fallacy’ in action – the false idea that there is only a fixed number of jobs to go around.

We have also been living through a period of sustained austerity with public services under severe pressure. People often find it hard to get a place in a good school for their kids or a doctor’s appointment. Since immigrants are also using public services, it is tempting to blame them for being ahead in the queue. Again, this is completely wrong as immigrants pay more in taxes than they take out in welfare, so they are on net subsidising public services for the UK-born. The fact that the government has chosen to use the fiscal benefits from immigration to pay down the budget deficit is hardly the fault of immigrants. But it is difficult for people to see this benefit. What is visible is competition for constrained public services, just like competition for jobs.

The stigmatisation of foreigners as a cause of our economic problems plays to deeply-based cultural fears. This is not simply bigotry, although some of it is. The anti-immigrant feeling would be there even if wages hadn’t fallen and public spending hadn’t been suffering years of austerity. But these real pressures helped lend credibility to the complaints. After all, what else is immigration but globalisation made flesh?

The media

Most of the British press has been unrelentingly Eurosceptic and anti-immigrant for decades. This built to a crescendo during the Brexit campaign with the most popular dailies like the Sun, Mail and Express little more than the propaganda arm of the Leave campaign.

The main alternative source of information for ordinary people was the BBC, which was particularly awful throughout the referendum debate. It supinely reported the breathtaking lies of the Leave campaign, in particular over the ‘£350m a week EU budget contribution’. Rather than confront Leave campaigners and call the claim untruthful, BBC broadcasters would say things like ‘now this is a contested figure, but let’s move on’. This created the impression that there was just some disagreement between the sides, whereas it was clearly a lie. It’s like saying ‘One side says that world is flat, but this is contested by Remain who say it is round. We’ll let you decide.’ The public broadcaster failed a basic duty of care to the British people. There was a need to tell people the truth for probably the most important vote any of us will have in our lifetimes. And the BBC failed.

The BBC also failed to reflect the consensus view of the economics profession on the harm of Brexit. A huge survey of British economists showed that for every one respondent who thought there would be economic benefits from Brexit over the next five years, there were 22 who thought we would be worse off. Yet time and again, there would always be some maverick Leave economist given equal airtime to anyone articulating the standard arguments.

The economics profession

There is much hand-wringing by economists over the role of the profession in the Brexit debate. It would certainly be a great thing if more academic economists were involved in talking to the public. Basic fallacies like thinking there is a fixed number of jobs, so immigration (and population growth for that matter) must be bad for unemployment are rampant. So more public engagement would certainly help. More support must be given to colleagues who help spread the economic news as there is a clear cost in time spent on public engagement versus time spent on other academic activities – research, teaching and admin.

Improving economic literacy cannot be solely accomplished by academics. This is an issue of basic skills that needs to be tackled in schools. As importantly, it needs to be addressed in the media where most journalists also seem painfully ignorant of basic economics.

But in the Brexit campaign, I doubt more effort by economists would have made any difference to the result. The economic consensus was clear. I directed the Centre for Economic Performance and no one could have tried any harder than we did to get the message out. This included being on TV and radio, blogging, travelling all over the country to give talks from Sunderland to Shropshire and even being livestreamed on Facebook with grime rapper, Big Narstie.

The problem was the press generally attacked or ignored us and the broadcasters gave equal weight to the small band of pro-Brexit economists. And of course, even when the message was presented clearly, many people would not listen or believe it. The usual clichés about not predicting the financial crisis were dutifully rolled out. As if the medical profession’s failure to predict the AIDS epidemic means that you should ignore your doctor’s advice to give up smoking. No, we cannot predict the date you will die of lung cancer, but if you smoke we can be pretty sure your health will suffer.

It should not be surprising that economics did not carry more weight in the vote. Academic economists receive relatively little attention in the media and have never been held in particularly high regard. And when the media does give space, it rarely uses academics, preferring to rely on City economists and think-tankers, despite the fact that polls suggest that academics are more trusted than all other groups except friends and family.

Politicians

The basis for increasing populism all around the world is economic insecurity caused primarily by the worst recession and recovery since the war. But some blame must also be apportioned to the UK’s current crop of politicians, who are surely the worst in living memory. David Cameron called an unnecessary referendum in order to steal some votes back from the far right. It was obviously going to become a vote on general grievances to kick the establishment, rather than about EU membership.

The weakness of Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn has precipitated a civil war that seems likely to end in his party’s disintegration.

The depths to which Leave politicians and their cronies stooped during the campaign deserve a special mention though for helping to destroy any semblance of rational discussion. Lies over the £350 million a week sent to the EU and the UK’s veto over Turkey becoming an EU member were repeated ad nauseum. I never thought I would experience such an Orwellian nightmare in my country. These lies, which were not robustly challenged in the media, cannot be punished in another general election and indeed, they have been rewarded by plum positions in the new government. And it worked: people ended up believing them.

For me, the nadir came a few days before the vote when one of Leave’s leaders, Michael Gove the Justice Secretary, compared me and my colleagues to paid Nazi scientists persecuting Einstein. This was apparently in response to a statement we signed (including 12 Nobel laureates) warning of the economic damage from Brexit. At least one of these derided experts had grandparents murdered in the concentration camps, so one can imagine how Gove’s statement – supported by Boris Johnson – made them feel.

Although this is a particularly nauseating episode, it simply capped off a frankly disgusting campaign, one where the Leave side simply impugned the motives of ‘the experts’ rather than seriously engaging with the substance of the economic debate.

The coming flood?

There are many other notable features of the Brexit vote – including the fact that Remain had a voting majority for those under 50 years of age and also in London, Scotland and Northern Ireland. It is shocking that a constitutional rupture can be made based on 37 per cent of the eligible voters. We take decades debating and prevaricating on major infrastructure projects like Heathrow and Hinkley Point, yet are prepared to gamble with something even more important for our futures on a simple one-off in-out referendum.

The referendum was won on a drumbeat of anti-foreigner sentiment. It’s the same tune being played by demagogues in every corner of the globe. It’s the same tune that was played in the 1930s. It’s the same old beat that rises in volume when people are afraid. In the UK, it’s echoed by a rabidly right-wing press and unchallenged by a flaccid establishment media. Mixed by a band of unscrupulous liars and political zealots, it has become a tsunami of bile that has downed and drowned a once great nation. The only question is which other countries will now be swept along in this poisonous flood.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the BrexitVote blog, nor the LSE. It first appeared at the LSE British Politics and Policy blog.

John Van Reenen has been the Director of the Centre of Economic Performance and a Professor of Economics at LSE since 2003. He is moving this month to be a tenured Professor at the Massachusetts Institute for Technology (MIT) jointly in the Department of Economics and the Sloan School of Management. His most recent publications are a book on the long-term economic effects of Brexit, on innovation and climate change and on productivity and trade.

“It is shocking that a constitutional rupture can be made based on 37 per cent of the eligible voters” – yet in 1972 the 2nd reading of the European Communities bill was secured by eight votes in parliament. So, if five had switched there would have been no 2nd reading. And the five most-marginal Tory seats at the 1972 election had a combined majority of 331 – so, in effect, this major ‘constitutional rupture’ was secured by the votes of just 166 people in five marginal constituencies. It as the 40-year failure to secure a proper buy-in that has led to the current pickle…

The biggest constitution rupture was signing up to an unelected foreign marxist dictatorship .

We did NOT lose the referendum, we won.

Poor guy! He suffers from what the French call une deformation professionelle. As an economist he cannot imagine people acting from other than economic motives. He also has a very biased opinion of the referendum campaign. Finally, he makes no attempt to be objective or to see the viewpoint of the Leave Campaign. The end result is a rather more sophisticated version of the ‘We wuz robbed by ignorant, racist, working-class scum’ argument already given room on this blog. Why he thinks people should listen to academic economic forecasts as the revelation of higher truth is incomprehensible. On big matters they are almost always wrong. John Kenneth Galbraith said that the only role of such forecasters was to give credibility to astrologers. Her Majesty the Queen famously asked LSE’s economists on the subject of the 2008-9 recession, when she visited the School, ‘Why did none of you see it coming?’ The record of economists in the UK hardly stands up: Churchill was advised to return to the Gold Standard at the pre-war level; the 1929 Labour Government was told it could not come off the Gold Standard; Harold Wilson was told not to devalue the pound in 1964; Thatcher was told to enter the ERM; Major was told not to leave it; according to the Economist, the great majority of economists believed Britain should adopt the euro; while notoriously 364 economists wrote to the Times in 1981 saying Thatcherite economics would never work. Why does he think most people ignore economists? It’s their record.

And what is his case for EU membership? Perhaps the working class in France, Italy, Greece, Spain and elsewhere are doing so much better than here? Maybe the obvious success of the euro outside Germany or Angela Merkel’s Willkommenspolitik or her deal with fascist Turkey (promised early visa-free travel and accelerated membership talks–or were these promises just lies?–) should clinch the argument?

Britain had already suffered from the CFP and CAP and ERM membership. Wisely she had opted out of Schengen and the euro and passed a Referendum Act to stop the transfer of more powers to Brussels. So she was already a semi-detached member of the EU before the EU referendum. Only 30% of Brits consider themselves European. The truth is that a majority of us wanted democratic self-government rather than citizenship of a failing wannabe supranational superstate. The result should not therefore have come as a shock -even to the British academic nomenklatura whose apparatchiks behaved like those from Russian and East European universities and academies during the Soviet era once the referendum was announced. No effort at objectivity or academic neutrality was made by these people. And this posting by one of them is proof that that effort is still lacking.

Good luck in America.

Thank you for articulating so well what so many of us feel.

I felt it particularly obtuse to complain about being compared to Nazi scientists at the same time he feels free to compare Leave voters to Nazi supporters of the 1930.

Both fool and hypocrite.

This Myth of the undemocratic, totalitarian and over-bearing European institutions is the Little Englander’s version of Goebbels’ Big Lie. Blame

everything on someone/something else and especially if that something is different to what you know or have experienced. How convenient to

absolve yourself of the failings in your own system and poke fingers at what you are told are the “Baddies”.

The notions of national sovereignty and self-determination in this globalised and money-oriented world are so outdated and redundant that it

beggars belief how anyone can still cling to them. National and even supranational governments are the hostages of forces way beyond their

control and even their knowledge half the time. The simple-minded idea that ANY national government has control over anything is too puerile

to be given credence.

But let us just take England’s control. How about borders? If, as seems highly likely Scotland and N.I break away into a Greater Celtic Union,

England will be surrounded on all sides by borders it has no meaningful control over whatsoever. Unless of course you take the Trump

approach and start building huge great walls and coastal gun emplacements. It is a nice fantasy that we can control access to English shores

but the reality is that the UK as presently constituted has a sea-border of 11,000 miles and only 25 fighting ships IN TOTAL to protect it. Even

assuming those ships were not already committed to other seas and duties it would require 24/7 12/12 duty rosters without breaks or refits,

refuelling or resupply for each ship to patrol 400 miles of coastline. Is it just me or is there a bloody great flaw in this notion? Do you consider

that sailors can stay awake 24/7? If refugees (they are NOT migrants) are willing to risk death to get to a safe place what are the REAL steps

you are willing to take to stop them? Sink them before arrival perhaps?

How about protecting our airspace? The RAF currently has about 54 serviceable war-planes which are already committed to Middle East

Theatres. All those Poles that are being told now to “GO HOME” are not going to enlist as their grandfathers did in order to protect our skies

again. And even if they did there are no planes for them to fly.

What of safeguarding our economy and power infrastructure? Who owns our industry? Who controls our water supplies? Where DOES our

electricity come from? Come on, you have all the answers it seems, tell us please just WHAT we DO control? (I already know the answers by

the way).

We are having to stitch up deals with the Chinese and French to build new generating plant. I can tell you, I have bought several items in the

past year, from shoes to tools with (supposedly) sharp edges all made in China and every single item has had to be returned because it broke.

And THIS is who England will have building our NUCLEAR power plant? THIS is the level of control you think is appropriate for a SOVEREIGN

nation?

How about our currency? Are you aware of the effect the referendum has had on our Pound? In what version of the Wizard of Oz does the B of

E have the power to control international currency trading or speculation? And just how would or could a UK government control the flow of

information or misinformation? We couldn’t even get our own Politicians to tell the truth.

Who makes the decisions about where and when to invest? Certainly not any UK Government of recent decades. If anything the only thing THEY

have done is to DIS-INVEST in Britain. How long has the discussion over HS2 or the 3rd Runway been going on? Who has decided which

factories will be built and where? Which entity has closed the steel industry and who exercises control over our manufacturing? Well, of course

not OUR manufacturing, the assembly of OTHER nations goods. How’re yah gonna keep ’em down on the farm after they’ve seen Pahree?

Fantasies of control but in the REAL world decisions are taken by the Money-Men and the Multi-national Corporations. Oh, for sure a

government can PRETEND it is exercising control, it can kid its electorate that “It’s OK, I’m in charge) but the strings are being pulled far away

from public scrutiny and accountability.

You argue that ceding authority to EU institutions damages our Sovereignty. So Good luck celebrating Independence Day – what are you gonna

tell The World Bank, IMF, WTO, UN Security Council, WHO, International Court of Justice, International Criminal Court, International Seabed

Authority, NATO,

International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea, Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, United Nations General Assembly, to

name just a few and to which the UK has obligations or has signed acceptances of their jurisdiction. Good luck telling Vladimir (Ras)Putin to

stay out of your backyard when he comes knocking. Somehow I don’t see HIM taking much notice of your SOVEREIGNTY.

So maybe an English Sovereign Government will finally get to grips with the weather. Gonna fix the floods huh? Stop the rivers overflowing

and the seas from crashing ashore? Bring back Canute, his time has come. Planning to introduce conscription to make up for all the fruit & veg

pickers who have run home to safety? Yes, let us pull the blanket over our head and pretend there isn’t a REAL world out there that DOESN’T

owe us a living or need us or even care if we continue to exist. Maybe you’ve heard, the Empire HAS fallen.

No, the truth is the only REAL control open to an English Government is how it will manage the decline and prevent people leaving the country.

I predict that within 10 years Teresa May will have instituted

border controls to keep people IN and currency regulation to prevent the flow of Capital OUT. You will be back in that Golden Era of nostalgia

when foreign holidays were the privilege of the rich and travel required permission.There’ll be no need to worry about immigration it’ll be

EMIGRATION that will have to be controlled. Don’t think it will happen huh? Well, I was born when it WAS happening and if I’ve learned

anything it’s that history has a habit of repeating itself.

You have done what all the Brexiters did – ignored the real-politik and cloaked your arguments in the Emperor’s Clothes. One day soon you will

realise just how chilly it has got out there and start crying for Mummy to bring your Blankie.

Oh, and don’t even get me started on the history of the development of nations or their governments.

As noted at the end of the piece, this was posted a few days ago at the politics branch of the LSE blog. There it was subjected to considerable derision in many of the 100+ comments, in my opinion richly deserved. I see that Alan Sked is continuing here. I can’t be bothered to add much more except to say that the biased, ill-informed, out-of touch groupthink shown here is one of the main reasons that the so-called experts are so derided.

completely agree I left the same comment under the other versions

I could accept the vote had we not been deliberately lied to and had decent clear debates. I’m sure a lot of people who voted were still confused and either didn’t vote or put an ‘X’ due to their 1=one fear of immigration.

Cameron deserted us when he should have carried on fighting. I believe we could have got better deals in the EU had he and the so called government fought harder. Better the devil you know being on the inside

We had no ‘fear’ of immigration just visceral anger as third world dregs poured into the country at our expense.

If you are angry at ‘third world’ immigration then you have not voted for any sort of solution to that. EU migrants tend to come from what you would call developed countries. The Leave vote will probably encourage more ‘third world’ immigration as business that do not want to pay decent wages will seek their semi-slave labour from elsewhere.

I appreciate that the large inward migration into the UK creates many challenges…Would you care to elaborate who these “third world dregs” are, exactly and what they deprive you of?

Well enjoy your moment of superiority you arrogant piece of **** You will be joining that 3rd World in the not so distant future. The problem you will be faced with is not people coming here to service your NHS Transport systems, road-sweeping, crop-picking, care homes but rather how to stop the Brain Drain as the young and intelligent. the compassionate and humanitarian, the outward looking rather than the xenophobes and bigots leave the shores of Albion and reach out to their friends and neighbours across the Channel.

Here is MY wish for my former homeland. Kick out ALL the non-white, non-passport holding residents of Britain, NO, England, (Scotland and Ireland have more humanity). Then explain away why tax receipts have plummeted, why hospitals have been closed, why trains and buses don’t run, why rats infest the streets, why the stench of rotting vegetables fills the air, why GP surgeries have shut, why care-homes don’t function, why your kids are hungry, why supermarkets can’t open, why schools are empty. Tell every one it is all the fault of those bloody foreigners for leaving you in the lurch as you swill your warm beer and vegetate in front of Top Gear.

Meanwhile I will be watching as 2 MILLION ex-pats are forcibly dumped on UK shores for you to take of.and laughing my head off in the South of France. As a FRENCH citizen.

Your comments are very, very stupid. I have seen them elsewhere, You need to grow up.

Alan Sked is right of course, the vote was not decided on economic grounds, it was won on the rather spurious notions of ‘taking back control’ over sovereignty and concerns about migration. if as widely forecast we now endure lower living standards as a consequence, it is of no significance. So when Cornwall demands continuation of its development funds, it should perhaps not be disappointed if there is a shortfall. Or maybe as very much looks like is going to be the case, we just print the money and hope for the best.

You people in office are not getting it! There are no permanet jobs , those on benefits

are suffering because Mr Cammeron took 75% of their money to enrich whereever ?

That is why we are out !

‘Their ‘ money is taxpayer’s money!

If this economist predicted the Leave vote (and I don’t remember or see any evidence for that) I can only presume he made a fortune going short on Sterling ?

As for the wage falls having “nothing to do with immigration” this must be a new theory of the price mechanism I haven’t previously heard before. Can he explain how a 10% increase in the supply of labour hasn’t lowered wages when all evidence is to the contrary? The link he has provided to a highly speculative piece talks of “increased productivity” due to migration but UK productivity has FALLEN. Yes migrants pay more in taxes than they claim initially, but what about the money they take out of the country when they return?

EXACTLY what is wrong with the electorate of England. Presuming to know and knowing nothing. Presumptions based on prejudice, unfounded assumptions, baseless innuendos, and a total lack of evidence of ANY kind, nature or description.

It must be fun having all that omnipotent insight and being able to see into the heart, mind and soul of someone you have never met let alone spoken to. With THAT talent for divining the motivations and actions of complete strangers you should be cleaning up at the racetrack.

So, I am going to use YOUR system of judgement and on that basis I can only presume you are a narrow-minded windbag with as much insight as an over ripe cantaloupe and the economic perspective of a pile of horse manure.

Which of us is using your system of divination correctly?

It is clear you didn’t now what you were voting for. The electorate clearly has a far better idea than you because it is you who and your ilk who have no evidence and are relying totally on prejudice and abuse.

Good analysis but perhaps there should be more about the psychological effect on voters of the Cameron government’s austerity policies Council cuts, library closures, school place shortages, unaffordable housing and childcare, cuts affecting sick and vulnerable people, government fights with junior doctors, etc – contrasted with private companies (e.g. G4S, Southern,) providing poor service but profiting greatly from public service franchises, inhumane work practices from the likes of Amazon and Sports Direct, widespread legal tax avoidance and truly disgusting money laundering, threats to our green belt yet so plenty of land for luxury flats & offices aimed at foreign speculators, plus ruinously expensive, apparently bad value projects like HS2 & Hinckley Point being imposed, often destructively, but, we surmise, presumably for the benefit of SOMEONE. All of this has little to do with the EU but everything to do with ordinary people seeing their own lives scorned but privileged cronies profiting and, we now see, having honours piled upon them. I am desperately sorry to see a Brexit vote, but I am also desperately sorry that the reckless hubristic over-entitled Cameron has been allowed to scamper off on holiday scot-free with his butt covered with that now rather famous pair of £250 swimming trunks.Amazing what a privileged background can do to protect people from the consequences of abject failure.

The decline started long before we joined the EEC.Britain was bankrupted by 2 World Wars and the loss of Empire. In point of fact the only growth Britain HAS seen during the last 80 years or so has been SINCE joining the EU. Issues of industrial decline, poor education, lack of infrastructure development (case in point the 3rd Runway for London has been under discussion since 2002 and STILL no decision has been reached – see also HS2) are and always have been the sole prerogative of National Gov’t’s.

I was a teacher in FE and we constantly struggled to keep up with changes in policy, exams, student outcomes, sometimes not even a year went by without a new “Initiative” being imposed. I was made redundant (how the F**k can a teacher be redundant?) after cutbacks in financing for FE under Labour. This was not the responsibility of the EU, they had NO say. This was BRITISH government decisions to abandon the needs of the most vulnerable. It was part of our SOVEREIGNTY which apparently we don’t have.

The EU has NO say whatsoever over national plans for house-building for example, this is the SOLE prerogative of successive UK politicians. For decades they have been warned that the housing stock is diminishing but it resulted in rising house prices for Middle Class Tories so their wealth went up whilst nurses, policemen, doctors, teachers couldn’t afford to live with travelling distance of their workplaces.

I WAS a Tory, stood for election and everything. I saw the truth first hand, saw Labour Party apparatchiks telling council tenants to be grateful they had a roof over their heads and to stop complaining about the

damp walls and broken lifts etc. I witnessed the back-biting and political in-fighting of my own party that ignored the needs of the populace in favour of personal ambition and promotion. Consecutive British PM’s have complained and niggled and demanded special treatment and exemptions and vetoes that no one else had. All in the name of BRITAIN IS GREAT and you must give us what we want. THESE are just SOME of

the reasons that England does not DESERVE EU membership and now they will get what they wished for. Good luck with that.

I hear the assassins talking about “getting the best deal for Britain’s exit”. Just what planet do these people come from?

There is NO deal to be done. When the program triggered by Article 50 is over Britain (or what’s left of it) will be OUT. FULL STOP NO NEGOTIATION! No cosy little deals, no special treatment for the country that reneged on the deals it had already been given. Britain had the MOST favourable treatment of the whole EU and it still wasn’t enough. Who the hell do you think you are? In what episode of the Phantom Zone do you think you are that the rest of the world owes you a living? When will you wake up and smell the fires burning around you?

Best possible deal my Aunt Fanny!!.

What I want to know is this: Will the current bruised crop of MP’s & MEP’s apologise to the people of the UK when the Union has disintegrated, when the economy is in the toilet, and the rest of the world has turned it’s back on a nation that tore up it’s treaties and obligations? Will they pay back to the Treasury the salaries and expenses they received for destroying the country? Or will it be self-justification and excuses, excuses, excuses? As per usual.

“There is no possibility of Turkey joining the EU in decades,” he said. Though the possibility of another referendum within decades is just as remote.

And do you see a vision of Turkey EVER in 500 YEARS becoming a member state NOW? At all? In ANY circumstances? Whatsoever?