Arbitration

- About arbitration

- Arbitration and human rights

About arbitration

Arbitration is a mechanism to settle disputes outside the traditional court system. In arbitration, the disputing parties submit their dispute to an arbitral tribunal, which considers the parties’ arguments and evidence, and then adjudicates the dispute. Arbitration can be used as a method to resolve disputes only if both parties have expressed their consent to do so. Their consent also includes the choice of the procedural rules that will govern the arbitration proceedings.

A decision of an arbitral tribunal (also known as an ‘award’) is binding on the parties and can be enforced in domestic courts. Accordingly, if a losing party refuses to abide by a decision, a winning party can request that a domestic court compel the losing party to comply with the award. Domestic court enforcement of an arbitral award is possible because most States are members of two major international treaties that recognise the binding character of these awards: the New York Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards of 1958 (the ‘New York Convention’) and the International Centre for the Settlement of Investment Disputes (‘ICSID’) Convention of 1965.

Institutional and ad hoc arbitration

Parties can choose to have their arbitration organised with or without the support of an arbitral institution. If the former, the arbitration is ‘institutional’; if the latter, the arbitration is ‘ad hoc’.

In institutional arbitration, the institution provides administrative support and establishes rules that govern the arbitration proceedings. The administrative support includes secretarial tasks such as facilitating communication between the parties and the tribunal, and record keeping. It also includes financial tasks that relate to the collection of parties’ payments to cover the costs of the proceedings, and also the fees charged by the arbitral tribunal. Arbitration rules cover issues such as the constitution of the tribunal, the potential participation of third parties, the rendering and possible publication of decisions, and the determination of costs. Importantly, the institution does not decide the case. The arbitral tribunal, appointed by the parties, adjudicates the dispute.

Alternatively, if the arbitration is ad hoc, there is no institution involved, and the administrative tasks, including the financial arrangements, are assigned to the arbitral tribunal. In this case, the arbitration proceedings will not be governed by institutional rules. Instead, parties can opt to draft their own set of rules or use the arbitration rules developed by the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (‘UNCITRAL Arbitration Rules’) for ad hoc arbitral proceedings.

Among the thousands of arbitral institutions worldwide, there are different types of organisations, both private and public. Major private institutions that provide commercial arbitration services include the International Chamber of Commerce (‘CC’), the London Court of International Arbitration (‘LCIA’) and the Stockholm Chamber of Commerce (‘SCC’). There are also hundreds of regional and national organisations that provide arbitration services to international disputes.

ICSID is the only public multilateral institution that provides arbitration services only in the context of international investment. The Permanent Court of Arbitration is another public multilateral organisation that provides a variety of dispute resolution services for disputes that involve States, international organisations and also private parties. However, unlike ICSID, its mandate is not restricted to international investment.

Commercial and investment arbitration

In the context of cross-border economic activity, two types of arbitration are particularly important: commercial arbitration and investment arbitration. However, the use of these terms is not consistent and may at times be confusing. This has resulted in part from the manner in which the arbitration mechanism and institutions have evolved.

Arbitration thrived within the business community to resolve disputes that were commercial in character during the first part of the twentieth century. In the context of international investment, investors were seeking a forum to resolve contractual disputes with host States that was independent from the host State itself. They began using arbitration. It was only when ICSID was created in 1965 that a specialised, non-commercial, forum was designed to handle investment disputes.

However, with the exponential grow of international investment agreements (‘IIAs’), which often provide for international arbitration, ICSID became the preferred forum for treaty-based disputes. Today, ICSID’s activity on State-investors contracts is marginal. Of the overall ICSID caseload, only 19% refer to contractual disputes. A significant number of these disputes continue to be submitted to commercial arbitration institutions.

When disputes are brought to ICSID relating to investment and arising out of a breach of a State-investor contract, an IIA or even a domestic law, they are generically referred to as investment arbitration. By contrast, where an investment dispute that arises out of an alleged breach of a State-investor contract is brought to a commercial arbitration institution, it will be considered commercial in nature and identified as part of commercial arbitration. This difference is not just in name. If disputes are brought to ICSID, and therefore part of investment arbitration, they are subject to ICSID registration and transparency requirements. Alternatively, commercial arbitration, institutional or ad hoc, would have no such requirements, unless the parties create them independently.

Finally, investment treaty arbitration or Investor-State Dispute Resolution (‘ISDS’) are the terms used when the dispute concerns an alleged breach of an IIA. The majority of known investment treaty arbitration cases are taken either before ICSID or to ad hoc arbitration using the UNCITRAL Arbitration Rules. It is unknown how many treaty arbitration cases are brought to commercial arbitration institutions as there is no public registry of these cases.

Arbitration and human rights

Over the last decade, concerns have been raised about investment treaty arbitration or ISDS by a wide range of stakeholders, including eminent figures of the arbitration practice and human rights advocates. These concerns relate to the unique nature of the protection provided to foreign investors under IIAs and the role of arbitral tribunals.

Disputes under IIAs call into question acts involving the exercise of public authority by the host State – including potentially any executive, legislative or judicial acts of the State at the national or sub-national level. The arbitration tribunal assesses such State acts based on broadly worded treaty standards that offer ample discretion in their application, without being restricted to following previous arbitration awards.

Criticism has address both the fact of private individuals (arbitrators) adjudicating the exercise of State public authority, and the broad discretion with which they do so.

Moreover, criticism of investment treaty arbitration has pointed to the lack of arbitrators’ contextualisation and accountability. Sundaresh Menon QC – Singapore’s Chief Justice and an eminent arbitration practitioner – has observed that arbitrators tend to come from a small pool of practitioners:

“… with experience in commercial law rather than in policy making. They are often unlikely to be attuned to the nuances of domestic public interest of the countries affected by their awards. This private model of international adjudication has allowed a select few individuals drawn from narrow specialities within international and commercial law to rule on issues of public policy and legality of state regulatory actions, with little or no accountability to the constituency.” (Key note speech, ICCA Congress 2012)

Concerns have been expressed both in relation to individual cases as well as in relation to a number of fundamental aspects of investment treaty arbitration. Some have even called into question its usefulness and legitimacy. Issues raised range from the inadequate transparency of disputes and the exclusion of interested third parties from arbitration proceedings, to the alleged undue restriction on the exercise of State regulatory power.

These concerns about ISDS are also expressed in human rights terms. Some of these concerns include that human rights impacts are not reflected in the arbitration process, that the lack of transparency is contrary to human rights and harm the public interest, that the capacity and willingness of States to regulate to protect human rights could be limited by potential liability under IIAs and that significant amounts of public money are wrongly diverted from public goods and services to pay for arbitration costs and awards.

The concerns raised about ISDS were also considered by Professor John Ruggie, former United Nations Special Special Representative on Business on Human Rights. Throughout his mandate, the Special Representative expressed his concerns about the potential limitation of state powers to fulfil human rights obligations, the lack of transparency and the exclusion of public interests considerations in arbitration proceedings. Among other things, he recommended that: “States, companies, the institutions supporting investments, and those designing arbitration procedures should work towards developing better means to balance investor interests and the needs of host States to discharge their human rights obligations.” (Report of the Special Representative A/HRC/8/5)

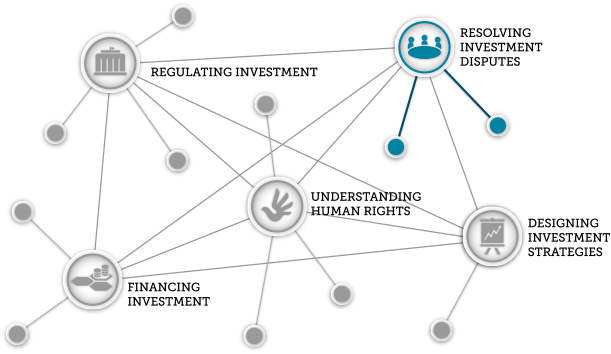

The Learning Hub’s resources will initially focus on investment treaty arbitration and human rights. The Hub has filmed an interview with Toby Landau QC, a prominent arbitration practitioner and barrister, in which he reflects on how human rights issues are relevant to investment arbitration, how these issues are being raised and handled in arbitration proceedings and the challenges this poses for arbitration practitioners and the protection of human rights.

The Learning Hub is developing an Arbitration Toolbox that would contain links to primary materials including international investment agreements and awards, resources that explain arbitration and resources that reflect current discussions concerning arbitration and human rights.

The Learning Hub will also invite reflection on whether and how human rights issues could be relevant for commercial arbitration. Two issues are of particular interest: the enforceability and application of stabilisation clauses in State-investor contracts and the potential impact of corporate responsibility to respect human rights on contractual claims between businesses.