International Human Rights Law

- What is international human rights law?

- States' human rights duties

- Connecting international human rights law and investment

What is international human rights law?

International human rights law is a firmly established part of public international law, and its main expression is found in international or regional treaties A treaty is an international agreement concluded between States governed by international law. They may also be called conventions or covenants. . Other branches of international law also operate to protect human rights such as international labour law and international humanitarian law (also known as the law of armed conflict).

The most widely recognised human rights instrument is the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights (“UDHR”). While a ‘declaration’ is not itself legally binding, the rights recognised in the UDHR have been codified in two legally binding documents: the 1966 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (the “ICCPR”) and International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (the “ICESCR”).

The Covenant protecting civil and political rights addresses such things as the right to life, liberty and security of person; the right not to be subject to torture or other forms of cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment; freedom from slavery and forced labour; the right to peaceful assembly; and the right to freedom of movement and non-interference in family and personal life. The Covenant on economic, social and cultural rights protects rights such as the right to work and to form and join trade unions; to an adequate standard of living, education, health, and to take part in cultural life.

More than 150 States are parties to these Covenants. Together, the UDHR, the ICCPR and the ICESCR are known as the International Bill of Rights. States have also agreed a number of additional international human rights conventions that further elaborate on issues such as discrimination against women, racial discrimination, torture and children’s rights. The human rights of workers are protected in the International Labor Organisation’s (“ILO”) declarations and conventions, including the Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work and the eight core labour conventions.

The focus of the Learning Hub’s consideration of human rights-related challenges begins with international human rights law and the United Nations human rights regime. However, human rights are also recognised in regional human rights law through legal instruments such as the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, the American Convention on Human Rights, the Arab Charter on Human Rights and the European Convention on Human Rights.

Understanding the content of rights

While the catalogue of human rights is articulated in international agreements, those agreements themselves do not always identify the scope, content and contours of these rights, or address in detail how they should be protected, respected and fulfilled. Instead, additional materials provide further guidance. These materials include the views, commentary and determinations of “treaty bodies”, which officially monitor implementation by States of treaty obligations; recommendations made through the Universal Periodic Review process (discussed further below); decisions from regional human rights courts or commissions and writings by human rights Special Procedures Independent experts appointed by the UN Human Rights Council to address human rights issues in specific geographies or on specific themes. .

Enforcement of international human rights law

International human rights law can be enforced in a number of ways. There are State-to-State procedures, such as bringing a case before the International Court of Justice for violations of various human rights treaties. However, State-to-State human rights procedures are not commonly used. Importantly, other procedures have been developed to monitor States’ compliance with their human rights obligations. For example, States must regularly report to UN treaty bodies that monitor implementation of human rights treaties. In their reporting, States must describe how they have worked to comply with their duties under the treaty and progress realization of human rights in their jurisdiction. Civil society organisations also have the opportunity to contribute reports contributing further information and views on the State’s implementation progress for the treaty body to consider.

Additionally, five of the treaty bodies accept individual complaints by individuals, or their representatives, who claim that their rights under the treaty have been violated by the State. The complaints result in a quasi-judicial decision, and treaty monitoring bodies may recommend that States provide specific forms of redress, such as compensation or the release of people from prison. The Human Rights Council also accepts individual complaints for the purpose of identifying systematic violations. In response, certain measures may be taken, such as monitoring the situation or recommending that the State in question be provided with capacity-building support or advisory assistance.

Every four years, States must participate in the Universal Periodic Review conducted by the UN Human Rights Council. This process involves a three-hour dialogue based on the reports submitted by the State, a compilation of reports contributed by other stakeholders and a compilation of additional information obtained by the UN about the human rights situation in each State. The Review concludes with an outcome report that provides summary conclusions and recommendations. This report forms the basis of follow-up dialogue in subsequent reviews. It also provides an authoritative basis for civil society advocacy.

Importantly, States must report on their human rights performance under international human rights treaties even where there is no ongoing dispute or litigation. This reflects the the UN human rights regime’s commitment to preventing human rights violations, rather than simply adjudicating upon them.

Opportunities for individuals to bring complaints also exist under certain regional human rights commissions and courts. One characteristic that is common among all complaint procedures is that the individual must normally exhaust domestic remedies before bringing their complaint, unless they can show doing so would prove ineffective or unreasonably prolonged. This reflects the emphasis in international human rights law of domestic implementation of international legal duties of the State.

States’ human rights duties

International human rights treaties set out the catalogue of human rights and identify the duties of States under these treaties to protect, respect and fulfil the human rights protected by the treaties.

States must protect individuals and groups from infringements of their rights by the state and also by third parties, such as business enterprises. The State duty to protect also requires that when infringements occur, the State must take judicial, administrative, legislative or other appropriate steps to ensure that the affected rights-holder has access to an effective remedy. Effective remedies may include compensation, restitution, guarantees of non-repetition, changes in relevant law and public apologies.

The State duty to protect is often described as a standard of conduct, not result. This means that when an individual’s human rights are infringed by an actor that is not the State or an agent of the State, the State is not directly responsible for that infringement. However, the State can be responsible under international human rights law for failing to take appropriate steps to prevent, investigate, punish and redress the infringement.

States must also respect human rights, meaning they must refrain from interfering with or curtailing the enjoyment of the human rights set out in human rights treaties they have ratified.

Finally, States have an obligation to work towards fulfilling the human rights in the treaty, meaning they must proactively engage in activities to improve the enjoyment of rights. These obligations require States to use the full range of their administrative, regulatory and judicial powers, including passing and implementing appropriate laws as well as taking judicial and administrative steps, engaging in educational activities and using other appropriate means.

Implementation of States’ human rights duties

The implementation by States of their international human rights duties generally results in a number of measures being taken domestically, including through legal and regulatory frameworks. For example, States protect, respect and fulfil human rights by passing and implementing constitutional and legislative bills of rights, anti-discrimination laws, criminal codes, corporate regulation and public laws. Such measures may not refer to human rights expressly, but instead operate to protect human rights, for example by ensuring freedom of speech, prohibiting discrimination in employment or enabling access to essential health services. These human rights measures may directly place obligations on a range of actors, including the government and other public authorities, businesses, civil society organisations and also individuals.

States also work at the international level through multilateral organisations to protect human rights by developing standards and guidelines that guide the conduct of third parties, including business enterprises. More information on these standards are in the Learning Hub’s pages on ‘Investment-related standards’.

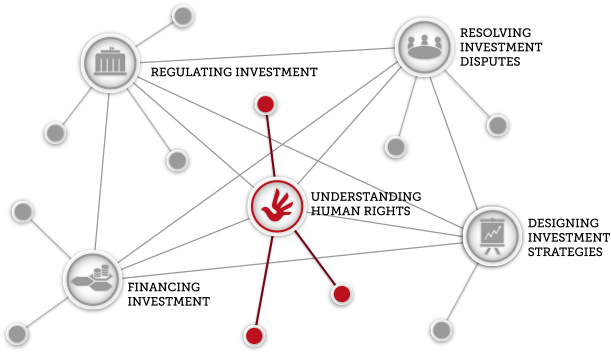

Connecting international human rights law and investment

Under International human rights law States create rights for individuals in the State’s territory and/or jurisdiction. On the other hand, under international investment agreements (IIA), States create rights for investors. In both cases, the State is under a legal obligation to abide by a treaty under international law. However, those State representatives in charge of implementing investment policy and those who are tasked with implementing human rights often work in their respective institutional silos, isolated from one another. This can result in investment policies that serve the narrow goals and incentives defined in investment-related departments, but that are blind to, or even work at cross-purposes to, the State’s human rights obligations.

The United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (“UNGPs”) address the need to improve the integration of human rights into other State policy areas like investment. The UNGPs invite questions such as: How do the State’s human rights obligations intersect with commitments made in investment treaties? How can the State avoid committing to contradictory requirements? Can State-investor contracts, investment treaties, or arbitration decisions impact a State’s ability to use its policy space to protect, respect or fulfil human rights?

Further, the increasing use of investment arbitration has raised a number of concerns about the impact of dispute resolution mechanisms. One specific area of concern is how State duties under international human rights law relate to interpretation IIAs during the resolution of investment disputes. For example, how do human rights norms sit with or qualify rights or obligations in the context of investment? How do decisions of human rights bodies interact with arbitral proceedings?

These very real and concrete questions highlight the urgent need to better understand the connections between international human rights law and investment, which are explored in the Learning Hub and in particular in the pages addressing ‘Regulating investment’ and ‘Resolving investment disputes’.