The last year has been like no other in US politics, with the perfect storm of a global pandemic and a concurrent botched federal response, and a president who engaged in continual misinformation and incited violence. Our ‘What Happened?‘ mini-series, has documented the key events since the 2020 general election, whilst also mapping important electoral trends. As the Biden administration begins to push through its legislative agenda, and by referring to pieces published in this mini-series as a core part of their source material, Peter Finn and Robert Ledger take stock of the tumultuous events of the past year, and the long term trends which have resulted from, or been accelerated by, the pandemic.

The last year has been like no other in US politics, with the perfect storm of a global pandemic and a concurrent botched federal response, and a president who engaged in continual misinformation and incited violence. Our ‘What Happened?‘ mini-series, has documented the key events since the 2020 general election, whilst also mapping important electoral trends. As the Biden administration begins to push through its legislative agenda, and by referring to pieces published in this mini-series as a core part of their source material, Peter Finn and Robert Ledger take stock of the tumultuous events of the past year, and the long term trends which have resulted from, or been accelerated by, the pandemic.

- Following the 2020 US General Election, our mini-series, ‘What Happened?’, explores aspects of elections at the presidential, Senate, House of Representative and state levels, and also reflects on what the election results will mean for US politics moving forward. If you are interested in contributing, please contact Rob Ledger (ledger@em.uni-frankfurt.de) or Peter Finn (p.finn@kingston.ac.uk).

How the Pandemic Changed the Election

As well as affecting the economy, the pandemic has had a significant impact on US elections, affecting, for instance, the date of 18 primaries held by the Democratic Party in 2020, as well as leading to cuts in the number of primary polling sites (Milwaukee, for instance, saw a cut from 180 to 5) and the shifting of party nomination conventions to all online affairs.

The 2020 US General Election, meanwhile, was like none that came before, with the COVID-19 pandemic driving logistical changes across the country and exacerbating political ruptures within and between political parties. Prominent Republicans supported Biden, whilst one of the three presidential debates was cancelled after Trump tested positive for COVID-19 in October.

Following the primaries, important logistical changes and challenges included large increases in the number of those choosing to vote early, whether in person or by mail and a concurrent shrinkage of the number of polling sites. According to reporting by Vice, in 2020 nationally there was a 20 percent drop in the number of polling sites compared with 2016.

Surmising how mail-in voting worked in November, Priscilla Southwell argued that ‘mail [voting] worked quite well in the United States during the 2020 General Election’, but also noted it was subject to a set of ‘mail suppression tactics’, seen in high rejection rates and a litany of lawsuits, reflecting longer-term trends of voter suppression. Adding a note of caution for those engaged in suppression, Southwell noted such tactics ‘may come back to haunt’ those who use them by suppressing their own ‘supporters’.

Key States for Biden and Trump

Whilst the headline of the election was Biden being the first presidential candidate to gain more than 80 million votes, with his victory confirmed four days after the election took place, a more nuanced and granular picture can be found by examining key states and exploring demographic trends in the voting data.

Writing about his native Minnesota, for example, Rubrick Biegon charted how Biden’s victory masked ‘a larger political realignment between the state’s urban and rural communities’, with Democrats becoming even more successful in urban and suburban areas and Republicans gaining voters in previous rural Democratic strongholds. Looking forward, Biegon argues that ‘Minnesota may remain a peculiar shade of purple for some time’.

Considering another increasingly purple state, the former Republican stronghold of Arizona, Eldrid Herrington documented how Biden’s victory was built on large changes in the demographics of the state, with a ‘350 percent increase in the Spanish-speaking population in the past 20 years, from 365,000 in 2000 to 1.3m in 2020, representing 24 percent of eligible voters as against 13.3 percent nationally’. Among these, ‘70 percent’ sided with Biden over Trump.

Writing about Florida, meanwhile, Kevin Fahey, looked at how Trump’s solid victory in the state, which saw Florida being ‘only one of eight states to swing towards former President Donald Trump in the 2020 election’, represented a turnaround from 20 years earlier, when the state was ‘8th-most competitive’.

Finally at the presidential level, writing about the Libertarian Party, whose time seems forever just over the horizon, Jeffrey Michels and Olivier Lewis argued the fall in the parties vote from 3.3 percent of the presidential vote in 2016 to 1.2 percent in 2020 reflected a dislike of Trump leading to many of their prior voters moving into the democratic camp in 2020, if only strategically, rather than a concerted rejection of the Libertarian Party itself.

Trends – more women in government; more men for Trump

Beyond the presidential election, an important trend was the increasing number of women elected at the House, Senate and state level. As Samantha Pettey wrote, ‘Republicans more than doubled the number of women serving in the House from 13 to 29, setting a new record’, with the Democratic Party also setting ‘a new House record with 89 women’ elected and states also ‘a new record of women serving in state legislatures by increasing the percent to 30.8 percent across all 50 states.’ Reflecting the importance of party identity, however, Pettey does ‘not expect any significant bipartisan women’s voting caucus in the 117th Congress, but rather party identity being the main predictor of behavior.’

Writing about ‘Trump’s unexpected gains among African-American and Latinx voters’ meanwhile, Dan Cassino argued that ‘it seems likely that Trump’s gains with these groups have less to do with race or ethnicity than they do with gender’, with segments of male voters in both communities persuaded by Trump’s appeals to a particular type of masculine identity.

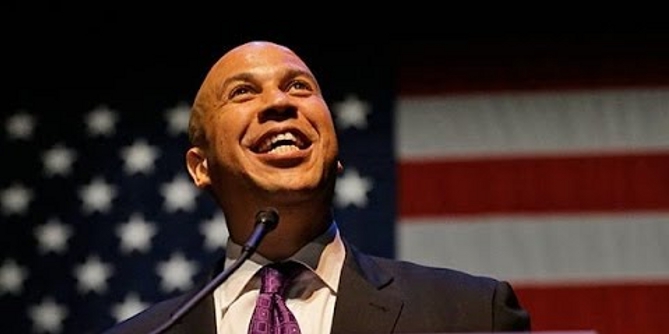

Photo by Gayatri Malhotra on Unsplash

Towards Impeachment

Despite Biden being declared the election winner on November 7th, 2020, Trump denied the result, largely as a result of the Democrat having secured a slow burn victory based on mail-in ballots, which took time to be counted. Trump, his supporters and those associated with him attempted to use legal avenues to challenge the legitimacy of Biden’s victory. In a particularly critical Pennsylvania dismissal, Judge Matthew Brann, labelled arguments designed to stop the votes of almost seven million people being counted a ‘Frankenstein’s Monster’. Whilst another ruling in the Keystone State noted that ‘calling an election unfair does not make it so’.

As we documented in December with Madison Imiola, alongside these legal attempts were consistent misleading statements, with Trump, in the first instance, calling for the counting of mail-in ballots to be stopped and, once Biden’s victory was confirmed, continually saying that the election was stolen, calling on people to challenge the election.

This continued until January 6th, when Biden’s victory was to be confirmed in a joint session of Congress whilst Trump simultaneously gave a speech to his supporters in Washington D.C.

Trump told his supporters ‘We won this election, and we won it by a landslide’ and that together they would ‘stop the steal’, stating that ‘We will never give up. We will never concede. It doesn’t happen’. He also said that ‘everyone here will soon be marching over to the Capitol building to peacefully and patriotically make your voices heard. […] We are going to the Capitol’.

Trump’s supporters then marched to the US Capitol, rioted, broke through police and security barriers, roaming the building and vandalising inside, breaking into offices and legislative chambers. Five people died either during or as a direct result of the riot; two Capitol Police officers who responded to the attack committed suicide in the days that followed.

These events led to Trump becoming the first president ever to be impeached twice (though not convicted by the Senate), whilst Biden assumed office on January 20th.

Biden’s first 100 days

Joe Biden has moved quickly since entering the White House, undoing a number of Trump initiatives and passing several progressive measures in executive actions. Recent weeks have seen negotiations over an economic stimulus and relief package aimed at lessening the economic impact of the pandemic. A version passed the Senate on March 6th. Among other things, this version, with a price tag of $1.9 trillion, includes an extension to unemployment benefits, stimulus checks and financial aid for state and local government. A final version was sent for Biden’s signature on March 10th.

Biden has so far been less keen to reach across the aisle and triangulate policy than many predicted. The senate victories in the Georgia runoffs in January have been crucial in this respect, giving Democrats control of both houses of congress. The new president has perhaps learned from his two democratic predecessors Barack Obama and Bill Clinton: the window for far-reaching policy making is narrow and making compromise with Republicans is often futile.

Thus far, this mini-series, along with its predecessor, has covered a number of the key trends of the past year, including demographic changes, new states moving into the ‘purple’ column, the rise of women candidates, and the growing distance between rural and urban voters, to name a few. Some of these are long-term shifts, some a result of the pandemic, some have accelerated due to the crisis. Others will only become apparent moving forward.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3d1o2GB

About the authors

Peter Finn – Kingston University

Peter Finn – Kingston University

Dr Peter Finn is a multi-award-winning Senior Lecturer in Politics at Kingston University. His research is focused on conceptualising the ways that the US and the UK attempt to embed impunity for violations of international law into their national security operations. He is also interested in US politics more generally, with a particular focus on presidential power and elections. He has, among other places, been featured in The Guardian, The Conversation, Open Democracy and Critical Military Studies.

Robert Ledger – Schiller University

Robert Ledger – Schiller University

Robert Ledger has a PhD in political science from Queen Mary University of London. He has worked for the European Stability Initiative, a think-tank in Brussels, lectured at several universities in London and currently lives in Frankfurt am Main. He is a Visiting Researcher (Gastwissenshaftler) in the History Seminar at Goethe University and also teaches at Schiller University Heidelberg and the Frankfurt School of Finance & Management. He is the author of Neoliberal Thought and Thatcherism: ‘A Transition From Here to There?’