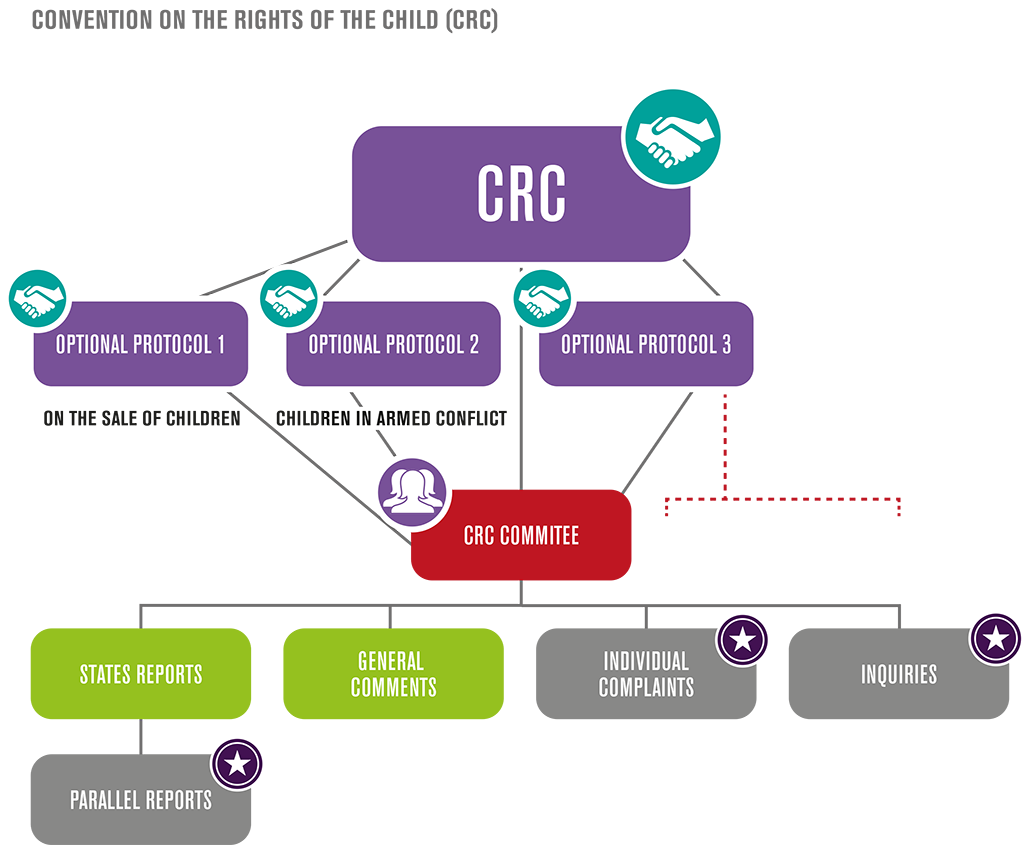

CRC | Optional Protocol 1 | Optional Protocol 2 | Optional Protocol 3 | CRC Committee | States Reports | Parallel Reports | General Comments | Individual Complaints | Inquiries

At a glance

Treaty: Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC)

Entered into force: 2 September 1990

Optional Protocol(s):

- Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the sale of children, child prostitution and child pornography (OPSC)

- Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the involvement of children in armed conflict (OPAC)

- Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on a communications procedure (OPIC)

Treaty Body: Committee on the Rights of the Child (CRC)

Location: Geneva

Meetings: Three times a year

Reports to: General Assembly, through ECOSOC

States must report: Within two years of ratification, then every five years afterwards or when requested by the Committee.

Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC)

Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC)

Entered into force: 2nd September 1990

The Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly (Resolution 44/25) on 29th November 1989. The Convention enshrines four common principles:

- Article 2: Non-discrimination (including by sex)

- Article 3: the best interest of the child

- Article 6: The right to life, survival and development

- Article 12: The views of the child

Boys and girls experience different vulnerabilities, often requiring different approaches to the practical application of the CRC rights. Working with the Committee on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, the Committee on the Rights of the Child has issued gender-specific general comments acknowledging these differences.

Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the sale of children, child prostitution and child pornography (OPSC)

Entered into force: 18 January 2002

The Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the sale of children, child prostitution and child pornography (OPSC) was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly (Resolution 54/263) on 25 May 2000. In Article 1, “States Parties shall prohibit the sale of children, child prostitution and child pornography”. States recognise, in its preamble, “that a number of particularly vulnerable groups, including girl children, are at greater risk of sexual exploitation and that girl children are disproportionately represented among the sexually exploited.”

Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the involvement of children in armed conflict (OPAC)

Entered into force: 12 February 2002

The Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the involvement of children in armed conflict (OPAC) was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly (Resolution 54/263) on 25 May 2000. The protocol aims to protect children from recruitment and use in hostilities. It also requires (Article 6) that states cooperate to support child victims of armed conflict. It includes protections, for victims, frequently girls, who are not “directly” involved in combat.

Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on a communications procedure

Entered into force: 14 April 2014

The Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on a communications procedure (OPIC) was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly (Resolution 66/138) on 19 December 2011. It establishes an individual complaints procedure which allows individual children to submit complaints regarding specific violations of their rights under the Convention and its first two optional protocols. It also establishes an inquiry procedure to investigate a specific country, should the treaty body receive evidence of grave and systematic violations of the rights set forth in the Convention or its Optional Protocols are taking place.

Committee on the Rights of the Child (CRC)

Committee on the Rights of the Child (CRC)

The Committee on the Rights of the Child (CRC) is the independent expert body appointed to oversee state parties’ implementation of the CRC and its Optional Protocols. It consists of 18 independent experts who are nationals of state parties to CRPD. They are elected by secret ballot and serve four-year terms. CRPD meets three times annually.

General Comments

In its General Comments, the Committee has addressed gender-based violence in relation to specific provisions in the CRC and state responsibility to eliminate it.

In its joint General Comment No. 18 of the CRC and General Recommendation No. 31 of the CEDAW Committee (4 November 2014), the Committee addresses state responsibility to eradicate harmful practices, such as forced and early marriage, female genital mutilation and crimes in the name of so-called “honour.” This joint General Comment situates itself in the context of CEDAW General Recommendation No. 19 on violence against women.

5. The CEDAW and CRC Committees consistently note that harmful practices are deeply rooted in societal attitudes according to which women and girls are regarded as inferior to men and boys based on stereotyped roles. They also highlight the gender dimension of violence and indicate that sex- and gender-based attitudes and stereotypes, power imbalances, inequalities and discrimination perpetuate the widespread existence of practices that often involve violence or coercion. It is also important to recall that the Committees are concerned that these practices are also used to justify gender-based violence as a form of “protection” or control of women1 and children in the home, community, school, other educational settings and institutions as well as in wider society. Moreover, the Committees draw States parties’ attention to the fact that, sex- and gender-based discrimination intersect with other factors that affect women2 and girls, in particular those who belong to, or are perceived as belonging to disadvantaged groups, and who are therefore at a higher risk of becoming victims of harmful practices.

6. Harmful practices are therefore grounded in discrimination based on sex, gender, age and other grounds and have often been justified by invoking socio-cultural and religious customs and values as well as misconceptions related to some disadvantaged groups of women and children. Overall, harmful practices are often associated with serious forms of violence or are themselves a form of violence against women and children. The nature and prevalence of these practices vary across regions and cultures; however, the most prevalent and well documented are female genital mutilation, child and/or forced marriage, polygamy, crimes committed in the name of so-called honour and dowry-related violence. As these practices are frequently raised before both Committees, and in some cases have been demonstrably reduced through legislative and programmatic approaches, this joint GR/GC will use them as key illustrative examples.

7. Harmful practices are endemic within a wide variety of communities in most countries of the world. Some of these practices are also found in regions or countries where they had not been previously documented, primarily due to migration, while in other countries where such practices had disappeared, due to a number of factors such as conflict situations, they are now re-emerging.

8. Many other practices have been identified as harmful practices which are all strongly connected to and reinforce socially constructed gender roles and systems of patriarchal power relations and sometimes reflect negative perceptions or discriminatory beliefs towards certain disadvantaged groups of women and children, including individuals with disabilities and albinism. These practices include, but are not limited to: neglect of girls (linked to the preferential care and treatment of boys), extreme dietary restrictions (forced feeding, food taboos, including during pregnancy), virginity testing and related practices, binding, scarring, branding/tribal marks, corporal punishment, stoning, violent initiation rites, widowhood practices, witchcraft, infanticide and incest.3 Harmful practices also include body modifications that are performed for the purpose of beauty or marriageability of girls and women (such as fattening, isolation, the use of lip discs and neck elongation with neck rings4) or in an attempt to protect girls from early pregnancy or from being subjected to sexual harassment and violence (such as breast ironing/“repassage”). In addition, many women and children throughout the world increasingly undergo medical treatment and/or plastic surgery to comply with social norms of the body and not for medical or health reasons and many are also pressured to be fashionably thin which has resulted in an epidemic of eating and health disorders.

This acknowledges the risks of re-victimization and harassment girl-survivors of violence, particularly harmful practices, face when accessing justice: ”Victims seeking justice for violations of their rights as a result of harmful practices often face stigmatization, a risk of re-victimization, harassment and possible retribution. Steps must therefore be taken to ensure that the rights of girls and women are protected throughout the legal process in accordance with articles 2 (c), 15 (b) and (c) of CEDAW and that children are enabled to effectively engage in court proceedings as part of their right to be heard under article 12 of CRC.” (paragraph 84)

72b) States parties should ensure that policies and measures take into account the different risks facing girls and boys in respect of various forms of violence in various settings. States should address all forms of gender discrimination as part of a comprehensive violence-prevention strategy. This includes addressing gender-based stereotypes, power imbalances, inequalities and discrimination which support and perpetuate the use of violence and coercion in the home, in school and educational settings, in communities, in the workplace, in institutions and in society more broadly. Men and boys must be actively encouraged as strategic partners and allies, and along with women and girls, must be provided with opportunities to increase their respect for one another and their understanding of how to stop gender discrimination and its violent manifestations…

72. Articles 34 and 35 of the Convention with consideration to the provisions of article 20, call on States to ensure that children are protected against sexual exploitation and abuse as well as the abduction, sale or traffic of children for any purposes. The Committee is concerned that indigenous children whose communities are affected by poverty and urban migration are at a high risk of becoming victims of sexual exploitation and trafficking. Young girls, particularly those not registered at birth, are especially vulnerable. In order to improve the protection of all children, including indigenous, States parties are encouraged to ratify and implement the Optional Protocol on the sale of children, child prostitution and child pornography.

15. Children with disabilities are more vulnerable to all forms of abuse be it mental, physical or sexual in all settings, including the family, schools, private and public institutions, inter alia alternative care, work environment and community at large. It is often quoted that children with disabilities are five times more likely to be victims of abuse. In the home and in institutions, children with disabilities are often subjected to mental and physical violence and sexual abuse, and they are also particularly vulnerable to neglect and negligent treatment since they often present an extra physical and financial burden on the family. In addition, the lack of access to a functional complaint receiving and monitoring mechanism is conducive to systematic and continuing abuse. School bullying is a particular form of violence that children are exposed to and more often than not, this form of abuse targets children with disabilities. Their particular vulnerability may be explained inter alia by the following main reasons:

(a) Their inability to hear, move, and dress, toilet, and bath independently increases their vulnerability to intrusive personal care or abuse;

(b) Living in isolation from parents, siblings, extended family and friends increases the likelihood of abuse;

(c) Should they have communication or intellectual impairments, they may be ignored, disbelieved or misunderstood should they complain about abuse;

(d) Parents or others taking care of the child may be under considerable pressure or stress because of physical, financial and emotional issues in caring for their child. Studies indicate that those under stress may be more likely to commit abuse;

(e) Children with disabilities are often wrongly perceived as being non-sexual and not having an understanding of their own bodies and, therefore, they can be targets of abusive people, particularly those who base abuse on sexuality.16. In addressing the issue of violence and abuse, States parties are urged to take all necessary measures for the prevention of abuse of and violence against children with disabilities, such as:

(a) Train and educate parents or others caring for the child to understand the risks and detect the signs of abuse of the child;

(b) Ensure that parents are vigilant about choosing caregivers and facilities for their children and improve their ability to detect abuse;

(c) Provide and encourage support groups for parents, siblings and others taking care of the child to assist them in caring for their children and coping with their disabilities;

(d) Ensure that children and caregivers know that the child is entitled as a matter of right to be treated with dignity and respect and they have the right to complain to appropriate authorities if those rights are breached;

(e) Ensure that schools take all measures to combat school bullying and pay particular attention to children with disabilities providing them with the necessary protection while maintaining their inclusion into the mainstream education system;

(f) Ensure that institutions providing care for children with disabilities are staffed with specially trained personnel, subject to appropriate standards, regularly monitored and evaluated, and have accessible and sensitive complaint mechanisms;

(g) Establish an accessible, child-sensitive complaint mechanism and a functioning monitoring system based on the Paris Principles (see paragraph 24 above);

(h) Take all necessary legislative measures required to punish and remove perpetrators from the home ensuring that the child is not deprived of his or her family and continue to live in a safe and healthy environment;

(i) Ensure the treatment and re-integration of victims of abuse and violence with a special focus on their overall recovery programmes.

…

44. In this context the Committee would also like to draw States parties’ attention to the report of the independent expert for the United Nations study on violence against children (A/61/299) which refers to children with disabilities as a group of children especially vulnerable to violence. The Committee encourages States parties to take all appropriate measures to implement the overarching recommendations and setting-specific recommendations contained in this report.Sterilization of children: which disproportionately affects girls

45. The Committee is deeply concerned about the prevailing practice of forced sterilisation of children with disabilities, particularly girls with disabilities. This practice, which still exists, seriously violates the right of the child to her or his physical integrity and results in adverse life-long physical and mental health effects. Therefore, the Committee urges States parties to prohibit by law the forced sterilisation of children on grounds of disability.

…

Vulnerabilities of refugee and internally displaced children.79. Certain disabilities result directly from the conditions that have led some individuals to become refugees or internally displaced persons, such as human-caused or natural disasters. For example, landmines and unexploded ordnance kill and injure refugee, internally displaced and resident children long after armed conflicts have ceased. Refugee and internally displaced children with disabilities are vulnerable to multiple forms of discrimination, particularly refugee and internally displaced girls with disabilities, who are more often than boys subject to abuse, including sexual abuse, neglect and exploitation. The Committee strongly emphasizes that refugee and internally displaced children with disabilities should be given high priority for special assistance, including preventative assistance, access to adequate health and social services, including psychosocial recovery and social reintegration. The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) has made children a policy priority and adopted several documents to guide its work in that area, including the Guidelines on Refugee Children in 1988, which are incorporated into UNHCR Policy on Refugee Children. The Committee also recommends that States parties take into account the Committee’s general comment No. 6 (2005) on the treatment of unaccompanied and separated children outside of their country of origin.”

11. Right to non‑discrimination. Article 2 ensures rights to every child, without discrimination of any kind. The Committee urges States parties to identify the implications of this principle for realizing rights in early childhood… Discrimination against girl children is a serious violation of rights, affecting their survival and all areas of their young lives as well as restricting their capacity to contribute positively to society. They may be victims of selective abortion, genital mutilation, neglect and infanticide, including through inadequate feeding in infancy. They may be expected to undertake excessive family responsibilities and deprived of opportunities to participate in early childhood and primary education… 36(g). Sexual abuse and exploitation (art. 34). Young children, especially girls, are vulnerable to early sexual abuse and exploitation within and outside families. Young children in difficult circumstances are at particular risk, for example girl children employed as domestic workers. Young children may also be victims of producers of pornography; this is covered by the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the sale of children, child prostitution and child pornography of 2002…

3. The Committee on the Rights of the Child noted “a number of protection gaps in the treatment of … children [who are unaccompanied or separated outside their country of origin], including the following: unaccompanied and separated children face greater risks of, inter alia, sexual exploitation and abuse, military recruitment, child labour (including for their foster families) and detention. They are often discriminated against and denied access to food, shelter, housing, health services and education. Unaccompanied and separated girls are at particular risk of gender-based violence, including domestic violence.

47. [In ensuring their access to healthcare, (arts. 23, 24 and 39) States] must assess and address the particular plight and vulnerabilities of such children. They should, in particular, take into account the fact that unaccompanied children have undergone separation from family members and have also, to varying degrees, experienced loss, trauma, disruption and violence. Many such children, in particular those who are refugees, have further experienced pervasive violence and the stress associated with a country afflicted by war. This may have created deep-rooted feelings of helplessness and undermined a child’s trust in others. Moreover, girls are particularly susceptible to marginalization, poverty and suffering during armed conflict, and many may have experienced gender-based violence in the context of armed conflict. The profound trauma experienced by many affected children calls for special sensitivity and attention in their care and rehabilitation.

48. The obligation under article 39 of the Convention sets out the duty of States to provide rehabilitation services to children who have been victims of any form of abuse, neglect, exploitation, torture, cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment or armed conflicts. In order to facilitate such recovery and reintegration, culturally appropriate and gender-sensitive mental health care should be developed and qualified psychosocial counselling provided.

…

50. Unaccompanied or separated children in a country outside their country of origin are particularly vulnerable to exploitation and abuse. Girls are at particular risk of being trafficked, including for purposes of sexual exploitation.

…

56. Child soldiers should be considered primarily as victims of armed conflict. Former child soldiers, who often find themselves unaccompanied or separated at the cessation of the conflict or following defection, shall be given all the necessary support services to enable reintegration into normal life, including necessary psychosocial counselling. Such children shall be identified and demobilized on a priority basis during any identification and separation operation. Child soldiers, in particular, those who are unaccompanied or separated, should not normally be interned, but rather, benefit from special protection and assistance measures, in particular as regards their demobilization and rehabilitation. Particular efforts must be made to provide support and facilitate the reintegration of girls who have been associated with the military, either as combatants or in any other capacity.

…

Reminding States of the need for age and gender-sensitive asylum procedures and an age and gender-sensitive interpretation of the refugee definition, the Committee highlights that under-age recruitment (including of girls for sexual services or forced marriage with the military) and direct or indirect participation in hostilities constitutes a serious human rights violation and thereby persecution, and should lead to the granting of refugee status where the well-founded fear of such recruitment or participation in hostilities is based on “reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion” (article 1A (2), 1951 Refugee Convention).

![]() Interested in other general comments? Browse all of the CRC’s general comments on the OHCHR website

Interested in other general comments? Browse all of the CRC’s general comments on the OHCHR website

State Reports

According to the General Reporting Guidelines for CRC:

States parties should provide information on the allocation of resources for social services in relation to total expenditure during the reporting period, [including] Child protection measures, including the prevention of violence, child labour and sexual exploitation, and rehabilitation programmes.

It is recommended that States parties provide data on the death of children under 18 years of age … as the result of crime and other forms of violence

States should provide data on the proportion of pregnant women who have access to, and benefit from, prenatal and postnatal health care, and the number of adolescents affected by early pregnancy

States parties should provide data on the number of children involved in sexual exploitation, including prostitution, pornography and trafficking;

(Revised guidelines under the OPSC)

Bearing in mind that article 9, paragraph 1 of the Protocol requires States parties to pay “particular attention” to the protection of children who are “especially vulnerable” to the sale of children, child prostitution or pornography, reports should describe the methods used to identify children who are especially vulnerable to such practices, such as street children, girls, children living in remote areas and those living in poverty. In addition, they should describe the social programmes and policies that have been adopted or strengthened to protect children, in particular especially vulnerable children, from such practices (e.g. in the areas of health and education), as well as any administrative or legal measures (other than those described in response to the guidelines contained in section V) that have been taken to protect children from these practices, including civil registry practices aimed at preventing abuse. Reports also should summarize any available data as to the impact of such social and other measures.

![]() Want more?

Want more?

- Read the full guidelines on state reporting on the OHCHR website

- Read the revised guidelines on state reporting of OPSC on the OHCHR website

![]() Parallel Reports

Parallel Reports

While state reports tend to provide information on legislative framework, they may not always thoroughly reflect the reality on the ground: for example, they may focus on domestic law, even though the implementation of that law for rights-holders may not be effective in practice. The Committee invites input from civil society to be used in their review of states’ reports (see section immediately above).This gives civil society actors the opportunity to present alternative evidence, views, findings and/or raise issues that are not covered by the state report. This input is submitted in the form of a report and parallel to the state report concerned. These reports are often referred to as “shadow reports” or “parallel reports”.

Interested in submitting a parallel report to the Committee?

General Information | Guidelines | Inclusion of children in the reporting process

![]() Want more? The UNHRC recommends the guides and case studies to the reporting process produced by Child Rights Connect, an NGO group which connects with CRC, states, and other international bodies

Want more? The UNHRC recommends the guides and case studies to the reporting process produced by Child Rights Connect, an NGO group which connects with CRC, states, and other international bodies

![]() Individual Complaints

Individual Complaints

Individual complaints may be submitted by or on behalf of an individual or group of individuals, within the jurisdiction of a state party, claiming to be victims of a violation by that state party of any of the rights set forth in any of the following instruments to which that state is a party: CRC, OPSC, OPAC.

Interested in submitting an individual complaint to the Committee?

Rules of Procedure | General procedures | Cases

![]() Inquiries

Inquiries

Does the CRC conduct inquiries? Yes (OPIC unless state has made a declaration under Article 14)

According to Article 14 of the optional protocol, If OPIC “If the Committee receives reliable information indicating grave or systematic violations by a State party of rights set forth in the Convention or in the Optional Protocols thereto on the sale of children, child prostitution and child pornography or on the involvement of children in armed conflict”, it may designate one of its Committee members to “conduct an inquiry and report urgently to the Committee”. This may include a visit to the country.

For more information on engaging with the UN treaty bodies, see ‘Working with the United Nations Programme: A Handbook for Civil Society’