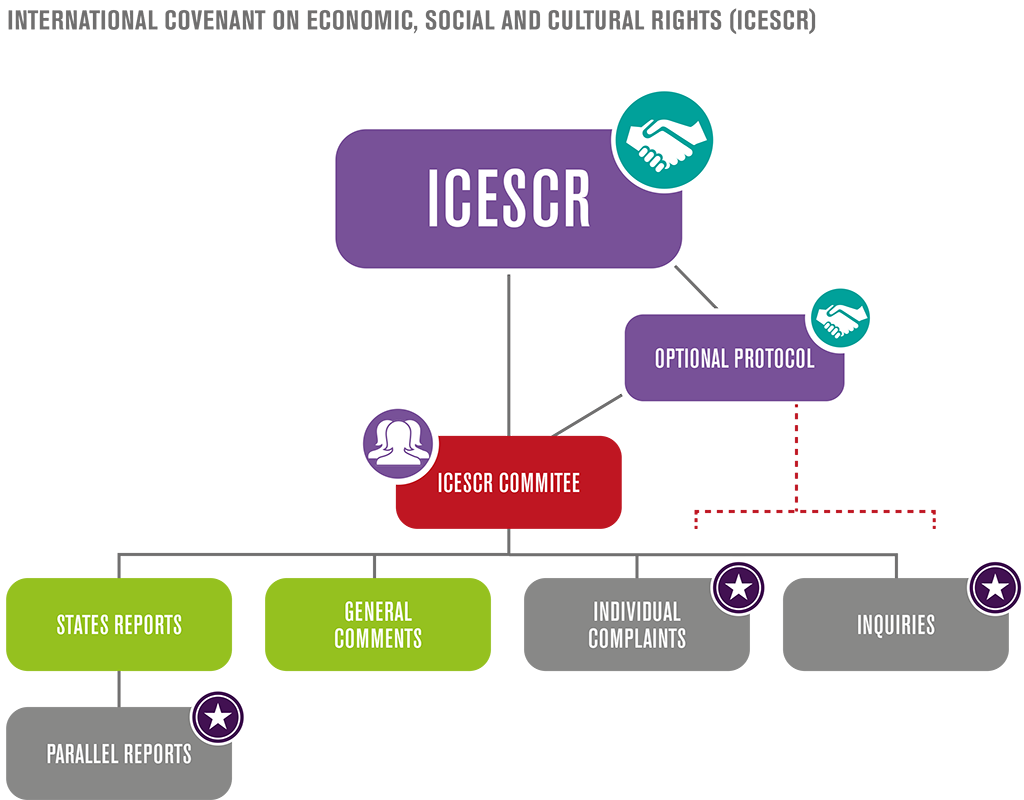

ICESCR | Optional Protocol | ICESCR Committee | States Reports | Parallel Reports | General Comments | Individual Complaints | Inquiries

At a glance

Treaty: International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR)

Entered into force: 3 January 1976

Optional Protocol(s): Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (OP-ICESCR)

Treaty Body: Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR)

Location: Geneva

Meetings: Twice per year

States must report: Within one year of ratification, and every 5 years. Committee may request more frequent reports if they have specific concerns.

Has your state ratified it? ICESCR | Optional Protocol

International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR)

International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR)

Entered into force: 3 January 1976

The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly (Resolution 2200 A (XXI)) on 16 December 1966. As one of two international treaties that make the ‘International Bill of Human Rights’ (along with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights), the ICESCR provides the legal framework to protect and preserve the most basic economic, social and cultural rights, including rights relating to work in just and favourable conditions, to social protection, to an adequate standard of living, to the highest attainable standards of physical and mental health, to education and to enjoyment of the benefits of cultural freedom and scientific progress. For this reason, most of the rights contained in the ICESCR are related to tackling VAW, given that VAW is a cause and consequence of women’s enjoyment of their human rights on a basis equal to men.

Some of the ICESCR’s articles most relevant to tackling VAW include:

- Article 2: right to non-discrimination and the right to an effective remedy

- Article 3: equal right of men and women to the enjoyment of economic, social and cultural rights in the ICESCR

- Article 6: right to work

- Article 7: right to just and favourable conditions of work

- Article 10: protection of the family, mothers, children and young persons

- Article 11: right to an adequate standard of living, including adequate food

- Article 12: right to health

- Article 13: right to education

- Article 14: primary education

- Article 15: right to participate in cultural life

Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (OP-ICESCR)

Entered into force: 5 May 2013

The Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (OP-ICESCR) was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly (Resolution A/RES/63/117) on 10 December 2008. It establishes mechanisms for bringing violations of economic, social and cultural rights before the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, specifically: an individual complaints mechanism, an inter-state complaint mechanism and an inquiry procedure.

Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR)

Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR)

The Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR) is the independent expert body appointed to oversee state parties’ implementation of the ICESCR. It consists of 18 independent experts who are nationals of state parties to ICESCR, elected by secret ballot and serving four-year terms. CESCR meets twice annually.

General Comments

In its General Comments, the Committee has addressed gender-based violence in relation to specific provisions in the ICESCR and state responsibility to eliminate it.

2. Due to numerous legal, procedural, practical and social barriers, people’s access to the full range of sexual and reproductive health facilities, services, goods and information is seriously restricted. In fact, the full enjoyment of the right to sexual and reproductive health remains a distant goal for millions of people, especially for women and girls, throughout the world. Certain individuals and population groups that experience multiple and intersecting forms of discrimination that exacerbate exclusion in both law and practice, such as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex persons (LGBTI) and persons with disabilities, the full enjoyment of the right to sexual and reproductive health is further restricted.In its general comment No. 14, the Committee stated that the right to the highest attainable standard of health not only included the absence of disease and infirmity and the right to the provision of preventive, curative and palliative health care, but also extended to the underlying determinants of health. The same is applicable to the right to sexual and reproductive health. It extends beyond sexual and reproductive health care to the underlying determinants of sexual and reproductive health, including access to safe and potable water, adequate sanitation, adequate food and nutrition, adequate housing, safe and healthy working conditions and environment, health-related education and information, and effective protection from all forms of violence, torture and discrimination and other human rights violations that have a negative impact on the right to sexual and reproductive health.

…

29. It is also important to undertake preventive, promotional and remedial action to shield all individuals from the harmful practices and norms and gender-based violence that deny them their full sexual and reproductive health, such as female genital mutilation, child and forced marriage and domestic and sexual violence, including marital rape, among other things. States parties must put in place laws, policies and programmes to prevent, address and remediate violations of the right of all individuals to autonomous decision-making on matters regarding their sexual and reproductive health, free from violence, coercion and discrimination.

30. Individuals belonging to particular groups may be disproportionately affected by intersectional discrimination in the context of sexual and reproductive health. As identified by the Committee, groups such as, but not limited to, poor women, persons with disabilities, migrants, indigenous or other ethnic minorities, adolescents, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex persons, and people living with HIV/AIDS are more likely to experience multiple discrimination. Trafficked and sexually exploited women, girls and boys are subject to violence, coercion and discrimination in their everyday lives, with their sexual and reproductive health at great risk. Also, women and girls living in conflict situations are disproportionately exposed to a high risk of violation of their rights, including through systematic rape, sexual slavery, forced pregnancy and forced sterilization. Measures to guarantee non-discrimination and substantive equality should be cognizant of and seek to overcome the often exacerbated impact that intersectional discrimination has on the realization of the right to sexual and reproductive health.

…

35. States must adopt the measures necessary to eliminate conditions and combat attitudes that perpetuate inequality and discrimination, particularly on the basis of gender, in order to enable all individuals and groups to enjoy sexual and reproductive health on the basis of equality. States must recognize, and take measures to rectify, entrenched social norms and power structures that impair the equal exercise of that right, such as gender roles, which have an impact on the social determinants of health. Such measures must address and eliminate discriminatory stereotypes, assumptions and norms concerning sexuality and reproduction that underlie restrictive laws and undermine the realization of sexual and reproductive health.

…

49. The core obligations include at least the following:

…

d) To enact and enforce the legal prohibition of harmful practices and gender-based violence, including female genital mutilation, child and forced marriages and domestic and sexual violence including marital rape, while ensuring privacy, confidentiality and free, informed and responsible decision-making, without coercion, discrimination or fear of violence, on individual’s sexual and reproductive needs and behaviours;

e) To take measures to prevent unsafe abortions and to provide post-abortion care and counselling for those in need;

…

58. Laws and policies that indirectly perpetuate coercive medical practices further violate this duty, including incentive or quota-based contraceptive policies and hormonal therapy, surgery or sterilization requirements for legal recognition of one’s gender identity. Violations of the obligation to respect also include state practices and policies that censor or withhold information, or present inaccurate, misrepresentative or discriminatory information, related to sexual and reproductive health.

59. Violations of the obligation to protect occur where a State fails to take effective steps to prevent third parties from undermining the enjoyment of the right to sexual and reproductive health. This includes the failure to prohibit and take measures to prevent all forms of violence and coercion committed by private individuals and entities, including domestic violence, rape including marital rape, and sexual assault, abuse and harassment, including during conflict, post-conflict and transition situations, and including violence targeting LGBTI persons or women seeking abortion or post-abortion care; harmful practices such as female genital mutilation; child and forced marriages; forced sterilization, forced abortion and forced pregnancy; and medically unnecessary, irreversible and involuntary surgery and treatment performed on intersex infants or children.

60. States must effectively monitor and regulate specific sectors, such as private health care providers, health insurance companies, educational and child-care institutions, institutional care facilities, refugee camps, prisons and other detention centres, to ensure that they do not undermine or violate individuals’ enjoyment of the right to sexual and reproductive health. States have an obligation to ensure that private health insurance companies do not refuse to cover sexual and reproductive health services. Furthermore, States also have an extraterritorial obligation to ensure that the transnational corporations, such as pharmaceutical companies operating globally, do not violate the right to sexual and reproductive health of people in other countries, for example through non-consensual testing of contraceptives or medical experiments.

…

64. States must ensure that all individuals have access to justice and to a meaningful and effective remedy in instances where the right to sexual and reproductive health is violated. Remedies include, but are not limited to, adequate, effective and prompt reparation in the form of restitution, compensation, rehabilitation, satisfaction and guarantees of non-repetition as appropriate. The effective exercise of the right to a remedy requires funding access to justice and information about the existence of these remedies. It is also important that the right to sexual and reproductive health is enshrined in laws and policies and is fully justiciable at the national level, and that judges, prosecutors and lawyers are made aware of that such a right can be enforced. Where third parties contravene the right to sexual and reproductive health, States must ensure that such violations are investigated and prosecuted, and that the perpetrators are held accountable, while the victims of such violations are provided with remedies.

20. The Covenant guarantees the equal right of men and women to the enjoyment of economic, social and cultural rights. Since the adoption of the Covenant, the notion of the prohibited ground “sex” has evolved considerably to cover not only physiological characteristics but also the social construction of gender stereotypes, prejudices and expected roles, which have created obstacles to the equal fulfilment of economic, social and cultural rights. Thus, the refusal to hire a woman, on the ground that she might become pregnant, or the allocation of low-level or part-time jobs to women based on the stereotypical assumption that, for example, they are unwilling to commit as much time to their work as men, constitutes discrimination. Refusal to grant paternity leave may also amount to discrimination against men.

…

31. Marital and family status may differ between individuals because, inter alia, they are married or unmarried, married under a particular legal regime, in a de facto relationship or one not recognized by law, divorced or widowed, live in an extended family or kinship group or have differing kinds of responsibility for children and dependants or a particular number of children. Differential treatment in access to social security benefits on the basis of whether an individual is married must be justified on reasonable and objective criteria. In certain cases, discrimination can also occur when an individual is unable to exercise a right protected by the Covenant because of his or her family status or can only do so with spousal consent or a relative’s concurrence or guarantee.

27. Article 10, paragraph 1, of the Covenant requires that States parties recognize that the widest possible protection and assistance should be accorded to the family, and that marriage must be entered into with the free consent of the intending spouses. Implementing article 3, in relation to article 10, requires States parties, inter alia, to provide victims of domestic violence, who are primarily female, with access to safe housing, remedies and redress for physical, mental and emotional damage; to ensure that men and women have an equal right to choose if, whom and when to marry – in particular, the legal age of marriage for men and women should be the same, and boys and girls should be protected equally from practices that promote child marriage, marriage by proxy, or coercion; and to ensure that women have equal rights to marital property and inheritance upon their husband’s death. Gender-based violence is a form of discrimination that inhibits the ability to enjoy rights and freedoms, including economic, social and cultural rights, on a basis of equality. States parties must take appropriate measures to eliminate violence against men and women and act with due diligence to prevent, investigate, mediate, punish and redress acts of violence against them by private actors.

50. In relation to article 13 (2), States have obligations to respect, protect and fulfil each of the “essential features” (availability, accessibility, acceptability, adaptability) of the right to education. By way of illustration, a State must respect the availability of education by not closing private schools; protect the accessibility of education by ensuring that third parties, including parents and employers, do not stop girls from going to school; fulfil (facilitate) the acceptability of education by taking positive measures to ensure that education is culturally appropriate for minorities and indigenous peoples, and of good quality for all; fulfil (provide) the adaptability of education by designing and providing resources for curricula which reflect the contemporary needs of students in a changing world; and fulfil (provide) the availability of education by actively developing a system of schools, including building classrooms, delivering programmes, providing teaching materials, training teachers and paying them domestically competitive salaries.

…

55. States parties have an obligation to ensure that communities and families are not dependent on child labour. The Committee especially affirms the importance of education in eliminating child labour and the obligations set out in article 7 (2) of the Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention, 1999 (Convention No. 182). Additionally, given article 2 (2), States parties are obliged to remove gender and other stereotyping which impedes the educational access of girls, women and other disadvantaged groups.

4. Plans of action prepared by States parties to the Covenant in accordance with article 14 are especially important as the work of the Committee has shown that the lack of educational opportunities for children often reinforces their subjection to various other human rights violations. For instance these children, who may live in abject poverty and not lead healthy lives, are particularly vulnerable to forced labour and other forms of exploitation. Moreover, there is a direct correlation between, for example, primary school enrolment levels for girls and major reductions in child marriages.

10. Women, children, youth, older persons, indigenous people, ethnic and other minorities, and other vulnerable individuals and groups all suffer disproportionately from the practice of forced eviction. Women in all groups are especially vulnerable given the extent of statutory and other forms of discrimination which often apply in relation to property rights (including home ownership) or rights of access to property or accommodation, and their particular vulnerability to acts of violence and sexual abuse when they are rendered homeless. The non-discrimination provisions of articles 2.2 and 3 of the Covenant impose an additional obligation upon Governments to ensure that, where evictions do occur, appropriate measures are taken to ensure that no form of discrimination is involved.

![]() Interested in other general comments? Browse all of the CESCR’s general comments on the OHCHR website

Interested in other general comments? Browse all of the CESCR’s general comments on the OHCHR website

State Reports

According to the General Reporting ICESCR Guidelines, states are required to report on specific aspects of gender-based violence:

“In relation to the rights recognized in the Covenant, the treaty-specific document should indicate:

…12. What steps have been taken to eliminate direct and indirect discrimination based on sex in relation to each of the rights recognized in the Covenant, and to ensure that men and women enjoy these rights on a basis of equality, in law and in fact?

13. Indicate whether the State party has adopted gender equality legislation and the progress achieved in the implementation of such legislation. Also indicate whether any gender-based assessment of the impact of legislation and policies has been undertaken to overcome traditional cultural stereotypes that continue to negatively affect the equal enjoyment of economic, social and cultural rights by men and women.

…34. Indicate how the State party guarantees the right of men and, particularly, women to enter into marriage with their full and free consent and to establish a family.

…40. Indicate:

a) Whether there is legislation in the State party that specifically criminalizes acts of domestic violence, in particular violence against women and children, including marital rape and sexual abuse of women and children and the number of registered cases, as well as the sanctions imposed on perpetrators;

b) Whether there is a national action plan to combat domestic violence, and the measures in place to support and rehabilitate victims; and

c) Public awareness-raising measures and training for law enforcement officials and other involved professionals on the criminal nature of acts of domestic violence.”

![]() Want more? Read the full guidelines on states reporting on the OHCHR website

Want more? Read the full guidelines on states reporting on the OHCHR website

![]() Parallel Reports

Parallel Reports

While state reports tend to provide information on legislative framework, they may not always thoroughly reflect the reality on the ground: for example, they may focus on domestic law, even though the implementation of that law for rights-holders may not be effective in practice. The Committee invites input from civil society to be used in their review of states’ reports (see section immediately above).This gives civil society actors the opportunity to present alternative evidence, views, findings and/or raise issues that are not covered by the state report. This input is submitted in the form of a report and parallel to the state report concerned. These reports are often referred to as “shadow reports” or “parallel reports”.

Interested in submitting a parallel report to the Committee?

Case Study: Women’s Human Rights Alliance’s report to CESCR on Ireland’s compliance with the ICESCR

Case Study: Women’s Human Rights Alliance’s report to CESCR on Ireland’s compliance with the ICESCR

Because state parties to the ICESCR are required to report on the gender-related dimensions of economic and social discrimination (including VAW), CSOs may also include information on VAW in their parallel reports to CESCR. This gives CSOs an opportunity to respond to any gaps in a state’s report and call attention to specific aspects of VAW that remain inadequately addressed.

In this parallel report submitted by the Women’s Rights Alliance, the organisation was able to draw CESCR’s attention to a specific restrictive law, the “Habitual Residence Condition” which they stated “has placed migrants, Travellers (who move across jurisdictions, generally from the UK to Ireland) and Roma in Ireland (and indeed returning Irish immigrants) in very vulnerable positions, whereby they cannot access any support services.”

This social and economic discrimination related to violence against women, because “…women trying to leave a situation of violence, if they do not have access to financial resources from the State, it can impact on their ability to successfully leave a violent relationship long term and it also impacts on their ability to access a refuge because a woman generally has to be in receipt of social welfare to access a refuge beyond an emergency period. Ireland must ensure that women experiencing violence are not subject to the Habitual Residence Condition when trying to access safety in a domestic violence situation.”

Following the submission of this report (in combination with other parallel reports submitted by NGOs/CSOs), CESCR issued concluding observations (8 July 2015) that identified discrimination against victims of ‘violence against women’ as an area of concern:

“21. The Committee is concerned at the discriminatory effect of the habitual residence condition on women who are victims of domestic violence, the homeless, migrants, Travellers and Roma in accessing social security benefits . It is also concerned at the lack of understanding of and clear guidelines for the relevant officials on the criteria applicable to decide on the condition (art. 9).

The Committee recommends that the State party review the habitual residence condition so as to eliminate its discriminatory impact on access to social security benefits , particularly among disadvantaged and marginalized individuals and groups, and ensure the consistent application of the criteria by providing clear guidelines and training to the relevant officials.”

![]() Want more?

Want more?

![]() Individual Complaints

Individual Complaints

Entered into force on 5 May 2013 with the adoption of OP-ICESCR

Individual complaints concerning VAW are often submitted to the Committee on the Elimination of all forms of Discrimination against Women, however cases involving multiple levels of discrimination can be submitted to other treaty bodies.

The Committee has stated that “Gender-based violence is a form of discrimination that inhibits the ability to enjoy rights and freedoms, including economic, social and cultural rights, on a basis of equality.” Whilst this new mechanism has not yet processed any violence against women related individual complaints, the procedure can be used by victims of a violation of any of the economic, social and cultural rights.

Interested in submitting an individual complaint to the Committee?

![]() Inquiries

Inquiries

Entered into force on 5 May 2013 with the adoption of OP-ICESCR

Under Article 11 of the optional protocol, if CESCR “receives reliable information on serious, grave or systemic violations” committed by a state party to the Optional Protocol, it may designate one of its Committee members to “conduct an inquiry and report urgently to the Committee”. This may include a visit to the country. However, if the state party concerned has opted out of under Article 11(8) of OP-ICESCR, the Committee may be prevented from carrying out an inquiry.

Interested in submitting information to the Committee?

Check if your state has made a declaration under Article 11 | Inquiry Procedure

For more information on engaging with the UN treaty bodies, see ‘Working with the United Nations Programme: A Handbook for Civil Society‘