After elections for the German Bundestag in September 2017, the phase of government formation has now ended, as the coalition between Christian democrats and social democrats has voted another cabinet under Chancellor Merkel into office last week. But the country, including the voters of the coalition partners, are deeply divided on the issue of migration. The political establishment needs to come to grips with that fact and respond to it, as political parties in neighbouring countries have done. Otherwise, the decline of Germany’s traditional parties may continue.

Elections for the Bundestag, Germany’s Lower House, took place on 24 September 2017. The social democrats (SPD) plunged to an all-time low in German federal elections, after having governed in a grand coalition with the Christian democrats for the past four years. Hours after election results came in, social democratic leader Martin Schulz already announced his party’s intention to return into parliamentary opposition.

But when the coalition talks involving Christian democrats, the Liberals and the Greens (dubbed “Jamaica”) failed in November, a renewed grand coalition began to emerge as the only realistic alternative to new elections. Three-way coalition talks were held, between the SPD, Angela Merkel’s CDU, and its Bavarian sister party, the CSU, resulting in a 170-page coalition agreement. A reshuffled cabinet with some fresh faces has now taken over the reins of governing again.

The degree of continuity that a refashioned version of the German grand coalition under the same Chancellor might suggest, needs to be put into perspective, however. In total, the three parties lost 13.7% of vote share since the previous round of elections in 2013. At the same time, the right-wing AfD made its entry into the Bundestag with a score of 12.6%. In 2013, it had narrowly failed to reach the electoral threshold of 5%. And while the party itself is notoriously fractured and disordered, its voters tell us relatively straightforwardly what their vote means: in infratest dimap’s exit poll, 92% of them say that the AfD is mainly there to influence the German government’s policy on refugees. In a separate poll ahead of the elections, a full 100% of AfD supporters declared (see page 30) that they were somewhat or very dissatisfied with Angela Merkel’s policy decisions on asylum and refugees.

The degree of continuity that a refashioned version of the German grand coalition under the same Chancellor might suggest, needs to be put into perspective, however. In total, the three parties lost 13.7% of vote share since the previous round of elections in 2013. At the same time, the right-wing AfD made its entry into the Bundestag with a score of 12.6%. In 2013, it had narrowly failed to reach the electoral threshold of 5%. And while the party itself is notoriously fractured and disordered, its voters tell us relatively straightforwardly what their vote means: in infratest dimap’s exit poll, 92% of them say that the AfD is mainly there to influence the German government’s policy on refugees. In a separate poll ahead of the elections, a full 100% of AfD supporters declared (see page 30) that they were somewhat or very dissatisfied with Angela Merkel’s policy decisions on asylum and refugees.

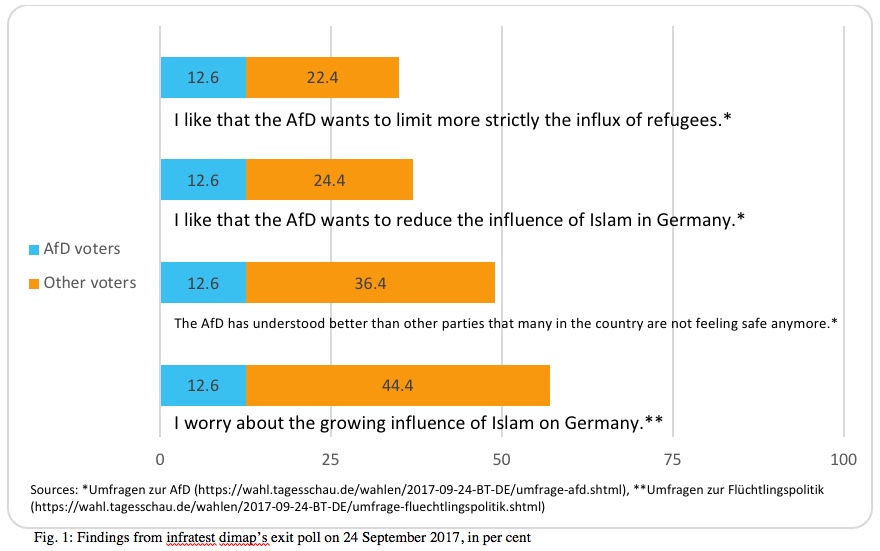

And while this opposition is clearly focused in the AfD, the general sentiment is shared more widely. We can see it in the exit poll. 35% of all voters like the fact that the AfD wants to limit the influx of refugees, while 37% approve of the party’s intention to reduce the influence of Islam on Germany, and 49% say that it has understood better than other parties that many in the country are not feeling safe anymore. 57% say that they worry about a growing influence of Islam. Assuming that all AfD voters agreed with the affirmations, that still leaves between 22% and 44% of the electorate either supporting the AfD’s general policy orientation on immigration, or sharing sentiments that the AfD has itself tapped into quite successfully (see Figure 1 below). Who are these voters?

Some of them will undoubtedly come from the CSU. The party has been the main exponent of criticism of German migration policy among the established parties, whilst being part of the governing coalition. Since the peak of the migrant crisis in late 2015, CSU politicians have sought to establish a more restrictive legal framework for humanitarian migration, in the form of a limitation on the intake of refugees and migrants (“Obergrenze”) around the order of 200,000 persons per year. Both the CDU and the SPD have categorically rejected the idea of a “hard” limit, but the CSU has not abandoned it, and so an on-again off-again debate about this proposal has dragged on for long. Still, due to the party’s geographical limitation to Bavaria, CSU voters only account for 6.2% of the whole electorate. So they alone can only make up a small piece of the rest. But we need look no further than the CDU and SPD.

First, both parties lost a considerable number of voters to the AfD: 980.000 from the Christian democrats, and 470.000 from the SPD. This is not surprising for either party. In the CDU’s base, some would like to see a closer alignment of their own party with the CSU on the issue of migration. In a poll in January, 44% of CDU and CSU voters (see page 11) agreed that Angela Merkel has not taken popular concerns about migration sufficiently into account in her policies. And, in a separate poll, when asked about the CSU’s call for a limit on the intake of refugees and migrants, 55% declared their support.

Among social democratic supporters, 54% also approved of this policy proposal. But criticism or skepticism around the issue of migration and integration are not new to the party. When, in 2010, social democratic politician Thilo Sarrazin published a controversial book on the failed integration of some immigrants in Germany, the reactions unveiled a rift in the party. His book was harshly criticized by party leaders, but in parts of the base, some of his ideas were received more favorably. Not so surprisingly then, 52% of SPD supporters were dissatisfied with the current German government’s migration policy ahead of the elections.

So, as we can see, the division in Germany’s electorate on the issue of migration extends far into the camps of the prospective coalition partners. Diverse viewpoints on a particular issue within a political party are nothing extraordinary of course. They may even be considered constitutive of the kind of big tent parties (“Volkspartei”) that both Christian democrats and social democrats see themselves as. But the coalition agreement between CDU/CSU and SPD does not reflect this division. In fact, the social democrats even pressed for an easing of restrictions on the reunification of families of migrants that had applied for asylum, but were not given the full legal status of refugees under German law. More generally, the agreement contains no indication that the government’s response to a renewed migrant crisis would be any different from that of 2015.

Taking furthermore into account that, since 2014, the political issue that voters identified as most important has been immigration and integration — currently leading 37 to 17 over pensions —, this produces a somewhat delicate situation. The three parties have adopted a stance that half of their supporters are opposed to, specifically on the one issue that voters tend to see as the most pressing. Here it is instructive to briefly consider the cases of the Netherlands and Austria, which have held general elections in 2017 as well. In both countries, the political parties have generally been responsive to the fact that migration has become voters’ top concern since 2015. Two candidates, that each made control of migration a key part of their platform and nudged their party to the right on this specific issue, went on to win the elections and form a government: the liberal Mark Rutte in the Netherlands, and Christian democrat Sebastian Kurz in Austria. In Germany, no such realignment with the electorate has taken place yet.

Since the parties of the grand coalition are, as we have seen, not accurately representing the division in their electorate on the issue of migration, the segment of the population that we have outlined above is being largely ignored in policy-making. The risk now is that support for established parties continues to erode as more voters move to the fringes of the political spectrum. Especially in the East German states, this is an acute concern. In the state of Saxony, the AfD already narrowly came out as the strongest force in the Bundestag elections. And one recent poll has the party closing in on the CDU in East Germany as a whole, with scores of 25% and 26%, respectively. But the party has also made inroads in urban districts in the South and West. Other voters may also not identify with any party on the ballot, and therefore stay home next time around. This disaffection from political parties happens gradually and is fairly silent, until it manifests itself all the more forcefully in another electoral upset of the coalition partners.

Therefore, it is imperative that the established parties, and first and foremost those who are now in government, formulate a political strategy to engage with their voters on both sides of the migration issue. Failure to do so may lead to a further erosion in future election scores. Germany’s political stability and the effectiveness of its government will decrease accordingly — at a time when leadership in Europe is very much needed.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Euro Crisis in the Press blog nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Christian Kloetzer is a freelance writer. He holds a BA in political science from the Université Libre de Bruxelles, an MSc in political science from the Vrije Universiteit Brussel, and an MA in political history from Utrecht University.

Related articles on LSE Euro Crisis in the Press:

Immigration, Welfare Chauvinism and the Support for Radical Right Parties in Europe

Germany’s (lack of) self-understanding