By Lucas Juan Manuel Alonso Alonso

This is the second and final part of Crony Capitalism and Neoliberal Paradigm, the first part was posted earlier on this very blog.

It is easy to see how almost all the European Union’s Member States, as well as other western advanced economies, are facing greater social inequalities, the spread of precarious/poorly-paid job conditions, greater tax burdens on households/SMEs, stagnation or slow economic growth together with high unemployment rates and cuts in core government functions. All these factors are leading to an impoverishment of the middle classes. From this picture arises, at least, one question: Is this situation a harsh consequence of a global economic crisis, or, on the contrary, the crisis is a response to a particular type of socio-economic paradigm—commonly known as “the system”? This article, divided in two parts, aims to answer that question: part 1, concentrates on negative socio-economic effects of crony capitalism, and part 2, deals with the relationship between crony capitalism and the global neoliberalism paradigm now reigning in most countries.

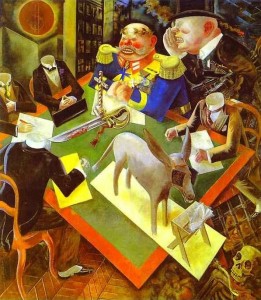

It seems that the neoliberalism paradigm now reigning in most countries systematically relies on cronyism: business people use political connections to get wealth, public works are not awarded to the best-qualified applicants but to those close to political power and so on. By doing so, this kind of neoliberalism is breaking the free market rules which “supposedly” form the basis of the model: genuine/creative entrepreneurs/enterprises are not rewarded on the basis of their effort and skills. Globally, this is reflected in the extreme concentration of wealth into the hands of a small and influential minority —at the very top of the social pyramid— leading to sharp social and economic inequalities.

It seems that the neoliberalism paradigm now reigning in most countries systematically relies on cronyism: business people use political connections to get wealth, public works are not awarded to the best-qualified applicants but to those close to political power and so on. By doing so, this kind of neoliberalism is breaking the free market rules which “supposedly” form the basis of the model: genuine/creative entrepreneurs/enterprises are not rewarded on the basis of their effort and skills. Globally, this is reflected in the extreme concentration of wealth into the hands of a small and influential minority —at the very top of the social pyramid— leading to sharp social and economic inequalities.

Neoliberal measures charge a greater tax rate on households and SMEs, meanwhile multinational companies and great fortunes experience less fiscal pressure—we have here one of the reasons why in many advanced economies the gap between poor and rich is widening (the concentration of income at the top of the income distribution increases inequality and decreases class mobility).

As such, several questions arise. Does neoliberalism allow class mobility? Empirically speaking, noticing the success of people related to political, economic or religious power, family’s wealth and status, it seems that access to the best education and subsequently prestigious positions are a matter of wallet size and/or relationship with some kind of factor power/family’s wealth and status rather than merit. If so, than is a talent crisis not a logical global consequence? How to recruit talented people without a real meritocracy? Wealthy individuals have more opportunities to study at the top universities of the world (mainly in business schools, economics, law and politics and other similar fields) than those with merit but lacking the financial means. Of course, there are scholarships and forms of financial support, but these will depend on the country we are talking about. On this particular point of mention the question should also be made about: What are the selection criteria for scholarships and how much is awarded? As a result of neoliberal measures increasing inequality, there is a lack of class mobility and, therefore, the subsequent socio-economic success is highly correlated with the above-mentioned factors.

If so, is there then a vicious circle? Obviously, the best universities and business schools in the world are going to prefer people related to power circles, because they are always going to undertake prominent roles in different parts of the world (governments, world organizations, top world companies…) but then, what about global leaders? Is a leadership without merit a true leadership? After all, those universities obtain prestige because their graduates get the best jobs in the world.

Below, I wish to articulate a few brief thoughts about the main general characteristics of this kind of neoliberal paradigm.