Nicci studied with the LSE Gender Institute as part of her Msc in Human Rights (2014-15). She hopes to go on to a PhD examining rape culture and violence against women.

“Sister to sister you sound my grief with your heart beats.”

(Ruth Graham 2012)

In the midst of dissertation writing season, from the 30th July to the 2nd August, the first ever festival about consent and sexual violence, Clear Lines, came to South London, in a bold attempt to replace the “shame and silence usually associated with this issue, with insight, understanding and community“. The festival, organised by Psychologist Dr Nina Burrowes and Artist Winnie M Li consisted of an exciting program packed with therapeutic workshops, plays, stand-up comedy and panel discussions, featuring around fifty speakers and facilitators. As a volunteer at the festival I was privileged to experience the compassionate atmosphere and openness of those running the events.

The timing of the festival was pertinent for me, as it coincided with the man who raped me in my room at University starting work as a junior doctor. Almost four years later, I still find it hard to comprehend how someone who hurt me in such a profound way has progressed to this position of responsibility with impunity. As is often the case with sexual assault, the perpetrator was someone I knew; a fellow student who lived in my stairwell. It wasn’t a stranger lurking in dark alleyway who followed me home one night as the stereotype would have you believe.

Myths about the perpetrators of sexual assault were the central feature in Dr Burrowes’ talk at the Clear Line’s Festival, “Why do they do it?”. She argued that reproducing the myth that the typical rapist is anonymous, hooded and lurks in back alleyways or parks serves to protect the majority of sex offenders who do not fit this stereotype.

Myths about the perpetrators of sexual assault were the central feature in Dr Burrowes’ talk at the Clear Line’s Festival, “Why do they do it?”. She argued that reproducing the myth that the typical rapist is anonymous, hooded and lurks in back alleyways or parks serves to protect the majority of sex offenders who do not fit this stereotype.

In her presentation, Nina illustrated how there is usually familiarity between survivors and those who attack them through projecting cartoons of perpetrators, based on her own facebook friends. Through these images, Dr Burrowes examined how sexual offenders relate to consent. She explained how some gain power and pleasure from purposefully disregarding consent, whilst others are unable to obtain it, and some employ self-deception, convincing themselves that the sex was consensual. The talk was unusual in its focus on the perpetrator, and indicates the direction that feminist activism on violence against women should be taking.

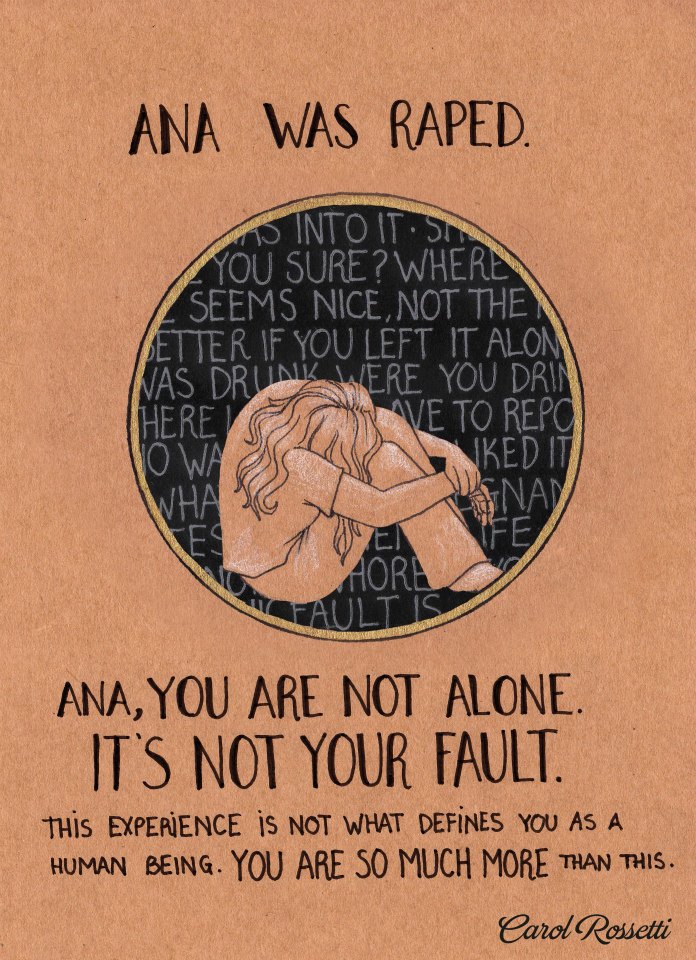

Feminist Activism concerning sexual violence usually involves “Speaking out” whereby a survivor shares their account of sexual assault in therapeutic and legal settlings; at demonstrations, through autobiographical literature (such as Alice Sebold’s Lucky) or online through internet based campaigns. This includes survivors’ groups such as the “Voices and Faces Project”, established in order to make sexual assault visible by putting, “names and faces on an issue that too often leaves its victims silent, and invisible“. As well as fulfilling therapeutic needs, speaking about sexual violence can constitute activism whereby, as Sara Ahmed has argued, “anger is creative; it works to create a language with which to respond to that which one is against” (2004:176). Sharing accounts of sexual violence has the potential to interrupt the public sphere and consequently challenge rape-culture.

Yet pervasive ideas about perpetrators mean that certain accounts of violent sexual assault at the hands of a stranger are more likely to be believed, receive empathy, be told and re-told. For example, it is no coincidence that the Guardian article, “sexual violence: leaving each individual University to deal with it isn’t working” focuses on accounts of stranger rape, despite the NUS report, “Hidden Marks“, indicating that students who sexually assault are predominantly students who are known to their victim.

Survivors whose experiences do not conform to the stereotype, survivors in marginalised positions and survivors who have experienced violence on multiple dimensions of disadvantage may be less believed, receive less empathy, and therefore be less likely to speak. The extent to which a survivor is believed is affected by the pervasive sexist, racist and classist structures that re-produce inequality both intentionally and unintentionally. Kimberle Crenshaw[1] notes that, “historically, black women’s words were not taken as true… Because black women were not expected to be chaste, similarly they were unlikely to tell the truth” (1991:1470). The violence experienced by survivors can thus be reproduced by the very process that supposedly enables emancipation.

However, survivors of sexual violence should not bear the responsibility for changing patriarchal, racist structures of oppression. In fact, over reliance on survivors speaking out inadvertently reinforces victim-blaming, as if the continuation of rape perpetration could be stopped if more people spoke out, reported their assault to the police… this is worryingly close to chastising people for “not fighting them off”, “leading them on” or “not saying no” – it is victim-blaming. Rape culture is not reproduced by survivors’ silence. It is reproduced by those who rape. And yet, rape survivors and victims have been widely studied, whilst the perpetrator remains invisible and unaccountable within feminism. It is by continuing and extending such focus on perpetration that rape culture can be effectively challenged, and hopefully, dismantled.

[1] Crenshaw, Kimberle. “Race, gender, and sexual harassment.” S. Cal. L. Rev. 65 (1991): 1467.