by Dean Cooper-Cunningham

In 2018, the UK celebrated the centenary of (some) women’s suffrage. This came on the back of the Global Women’s Marches that protested the election of Donald Trump following his anti-women statements and the more general anti-feminist sentiment (re)surging worldwide. What became clear from the Women’s Marches was the power of visual material in protests. Protestors used an abundance of visuals, both on- and offline, from the controversial Pussy Hats, live-streaming and sharing images on social media to more traditional printed posters. This visual aspect of political movements is often under-appreciated, especially when looking historically. This is true in the case of the British Women’s Suffrage movement where most argue that it was ‘Deeds, not words!’, actions not talk, that won women the vote. However, the poster was an important medium, used by both Government and Suffragettes, respectively, to try to silence Suffragettes and to showcase women’s poor treatment and status as second-class citizens. For suffragettes in particular, posters became fundamental for communicating their political goals and the extraordinary actions (e.g., hunger striking) they used to achieve those goals.

In this post, I draw on my recently published article Seeing (In)Security, Gender and Silencing: Posters In and About the British Women’s Suffrage Movement to demonstrate how it is crucial to consider the visual aspect of political movements and how they are used to circumvent oppression and bring attention to key political issues.

There is no denying that deeds helped the suffrage cause, however they were not the only mechanism through which Suffragettes demonstrated their politics and resisted the British government’s attempts to silence them and keep women outside of politics. By 1903, despite multiple requests by those pursuing women’s suffrage, a women’s vote had been repeatedly denied. As such, Emmeline Pankhurst founded the Women’s Suffrage and Political Union (WSPU), a militant organisation. She argued that drastic action was necessary because the peaceful words of the National Society for Women’s Suffrage (NSWS) and National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) were no longer helping the cause. While split on the best means to achieve suffrage, pro-suffrage groups were similar in their use of a new type of political spectacle (posters) and the production of a visual campaign that served their mutually desired end: the women’s vote.

Using posters, the Suffragettes focused on publicising the punitive measures used by the government against them. Alongside these images, which showcased women’s experiences as women and as Suffragettes, the Suffragettes carried out certain practices like window-smashing and hunger-striking in prison when they were arrested. This was all in a bid to increase attention for their cause. The posters were a way of bringing certain actions (especially hunger striking) to the public’s attention because they often took place in spaces inaccessible to public scrutiny – in prisons, for example. Without posters, many of the Suffragettes’ actions would otherwise have gone unseen.

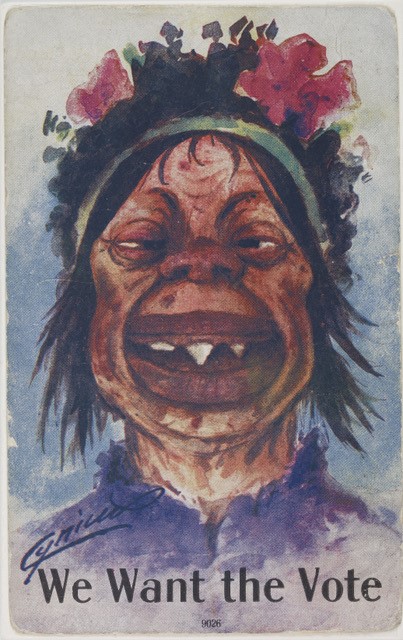

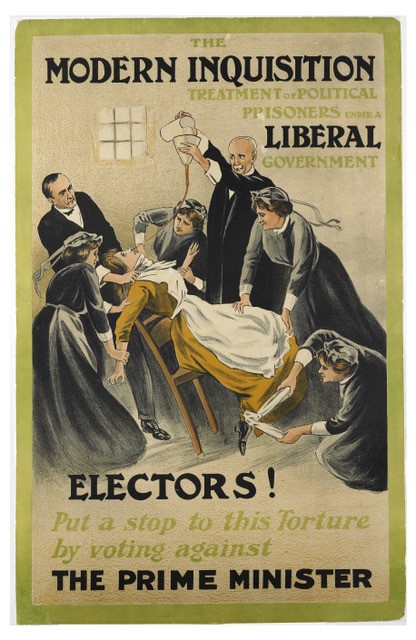

To illustrate the power of posters and their prominence in the Women’s Suffrage Movement, I now discuss two posters available from the London School of Economics’ Picture Library. These two posters – one anti-suffrage, the other pro-suffrage – touch on two key themes in pro- and anti-women’s suffrage imagery: self-sacrifice and monstrosity, respectively.

Monstrosity

Suffragette militancy, which included blowing up post boxes and window-smashing, caused all of the women pursuing suffrage, including those who were peaceful, to be cast as ‘mad’ and ‘unladylike’ monsters. This is best seen in anti-suffrage imagery, which was replete with themes of sexual deviance, monstrosity, masculine insecurity and the feminisation of British male elites. The British Government, drawing on women’s resistance to patriarchal gender norms, started to depict the Suffragettes’ as a threat to societal stability and political order. By doing this they suggested that if women were allowed to vote, the fabric of society would be at risk. The patriarchal status quo relied on the linking of women’s political actions with mental dysfunction and subhuman monstrosity. As such, the British government sought to punish the Suffragettes for the radical “unfemininity” of political action.

Image credit: Anonymous, We Want the Vote (1908). Source: Museum of London, image no. 010260. LSE Library; Museum of London Picture Library.

The ‘We Want the Vote’ poster illustrates the Government’s attempt to demonise Suffragettes. It shows a deformed individual with short brown hair. We can identify the woman as a Suffragette by their purple top, green hairband—both of which were key WSPU colours—and pink flowers in her hair. The Suffragette is alone, looks excessively masculine and animal-like, which runs against then-prevalent ideas of beauty and femininity. She has sharp fangs, exaggerated features and looks unclean, which works to signal her dangerousness and monstrosity. This person becomes a symbol of bad womanhood, they are flawed femininity incarnate. The individual stands against a blue background, which, given the association of blue with masculinity, can be said to indicate her opposition to traditional gender roles. Here, colour is used as a way of delegitimising the Suffragettes’ cause: it marks the abnormal, unnatural, intrusion of women into ‘men’s’ political space. Any ambiguity about the subject of the poster—that is, if one were totally unaware of WSPU colours and the women’s movement—is negotiated with the on-poster text “We Want the Vote”. The text explicitly links the poster to enfranchisement and the illustration identifies it as anti-women’s suffrage. This was a powerful visual that captured broader government narratives of Suffragettes’ as dangerous.

Self Sacrifice

Suffragettes were denied political prisoner status, which granted prisoners more rights and comforts. As such, imprisoned Suffragettes began hunger-striking. Responding to this, the Government started force-feeding Suffragettes, arguing that Suffragettes were mentally disordered and monstrous, like in the ‘We Want the Vote’ poster. Force-feeding was a practice ordinarily reserved for mentally ill patients/prisoners. Its use was permitted out of fear that a Suffragette’s death would increase support for their cause, which raises questions about whether Suffragettes were genuinely perceived as mentally ill or whether this was a political strategy. Force-feeding actually martyred the Suffragettes, giving them a platform from which to project their voice and the visuals to support it. The women enduring torture gained admiration as people became aware of their ordeal through the posters. Recognising this, the WSPU’s strategy was to show how Suffragettes were treated in prison to rally support and provoke a reaction.

Image credit: Alfred Pearse for WSPU, The Modern Inquisition (1910). Source: Museum of London, image no. 001313′. LSE Library; Museum of London Picture Library.

By illustrating the government’s actions and Suffragettes’ endurance of force-feeding in prisons became a way of communicating with an audience that was otherwise unable to see the effects of torture because it took place in prison. ‘The Modern Inquisition’ poster does precisely this: it was crucial to the cause and widely circulated. This and similar images were fundamental to showcasing dominant conceptions of women as inferior and deranged; how they were treated differently to men. Other prisoners, especially those granted political prisoner status, were not force-fed unless diagnosed with a mental illness. This reinforces the idea that political women were understood to be abnormal, defunct, and mentally disordered.

By visualising women’s experiences, posters emphasised the poor treatment of women and Suffragettes’ while also showing the extremes Suffragettes went to in confronting patriarchy. They made visual moves to construct the government as threatening to suffragette prisoners’, and more generally women’s, lives. These posters circulated nationally and communicated to the public women’s experiences to a greater degree than talk of force-feeding alone could. It rendered the unimaginable imaginable by showing events. It also inspired action. Posters of force-feeding and women’s suffering became crucial to revealing women’s insecurities by calling attention to the pervasiveness of patriarchal controls over their bodies and the definitions of acceptable femininity that constrained women to the domestic, private, sphere.

So, to address the titular question: is a picture worth a thousand words? The short answer is: not exactly. The longer answer is: we don’t decipher images outside of a given context and that context includes both the things we do (‘practices’) and the things we say (‘textual’ or ‘verbal’). Thus, while an image may appear to capture a story in a simple, quick-read way, we need to be aware of all the stuff – the practices, speech, and other visuals – that comes before that image and give meaning to what it depicts. We can’t decode an image (e.g., Phan Thi Kim Phuc’s Napalm Girl) without having some understanding of the thousand words it supposedly summarises. Essentially, that means that an image could be worth a thousand words but that is predicated on ‘knowing’ (some of) those thousand words already. Images and what they show also allow us to think about the unsaid, the unsayable, the things that if said, even though implicitly knowable, might cause us harm. What I wanted to do in this post is show that images are important parts of political movements that go hand-in-hand with texts, speeches and practices, like protests and hunger-striking, as ways of furthering their cause and drawing attention to the political issues they wish to get (higher) on the agenda.

In the case of the Suffragettes, a combination of texts, visuals and practices was used to show and tell stories. Each of these mediums gave meaning to the others to constitute the women’s cause and none should be privileged over the others. To do so loses the complexity of the politics at play. Increasingly, we are seeing similar combinations of texts, images, and practices as women and people marginalized because of their non-normative sexuality, gender identity, race, class and/or ability protest their political and social subjugation. If we are to fully understand the threats real people face, articulated in/by (global and local) political movements, we must turn attention to the ways that images show things that may otherwise go unsaid. We must think through the ways that images may just speak, or at least compliment, a thousand words.

Dean Cooper-Cunningham is a Ph.D. Fellow at the University of Copenhagen. He works at the intersections of visual politics, feminist and Queer theories, and critical security studies. His current research focuses on the ways that sexual orientation- and gender- specific (in)securities are constituted by images. It examines the articulation of (in)security by Queer individuals and groups, as well as the ways that these individuals are constructed as dangers to society and politics by government and societal actors.

Dean Cooper-Cunningham is a Ph.D. Fellow at the University of Copenhagen. He works at the intersections of visual politics, feminist and Queer theories, and critical security studies. His current research focuses on the ways that sexual orientation- and gender- specific (in)securities are constituted by images. It examines the articulation of (in)security by Queer individuals and groups, as well as the ways that these individuals are constructed as dangers to society and politics by government and societal actors.