By Alexandra Tomaselli

In this post, I focus on the gender employment gap of women with migrant backgrounds in a multilingual, small and rich province in the very North of Italy, i.e., South Tyrol or the Province of Bolzano. I argue that an intersectional analysis, which explores the effects and the role of a variety of social drivers and external factors, may offer a more in-depth explanation as to why these women are essentially excluded from the labour market, even in areas such as South Tyrol, where the unemployment rate is extremely low. In addition, I show how local laws and policies may play a crucial role in achieving gender equality but they must integrate an intersectional approach – an aspect that at the moment is essentially ignored.

The gender employment gap

The gender employment gap is a persistent and ubiquitous reality despite more than a century of struggles, the recognition of equality rights, and the adoption of several policies at the EU to the local level. As is well-known, the pandemic has further exacerbated existing social inequalities, and, among others, women have been hit the hardest. The 2022 European Gender Equality Index tells us that gender equality is improving but at a glacial pace since 2010: the average for the entire EU is 68.8 out of 100 for 2022 (in the early 2010s it was 63.1). In the domain of work, where gender equality is measured as being up to 71.1 out of 100, the average participation of women in the labour force per se is quite high but the quality of the work remains low. Horizontal and vertical segregation (i.e., related to some types of occupations or relegated to inferior positions only, respectively) is a widespread reality.

Although the 2022 report states that Italy is among those countries that are “catching up” in terms of gender equality, it also points out that Italy has the lowest score in the domain of work (63.2) and has worrying levels in terms of women’s participation in the labour force and the segregation and quality of work. Local statistical data shows that the Italian sub-state unit of South Tyrol has one of the lowest unemployment rates in the country, equal to 2.5% in the first trimester of 2022. The data also show that 69.9% of women in South Tyrol are employed—the highest trimestral value registered in the past five years. However, the data does not specify whether the women are employed part-time or full-time, does not note what positions they hold, and does not disclose the women’s background or identity characteristics. Furthermore, the data does not report on the illegal working conditions of undocumented people, thus excluding them from statistics. As stressed by Oesch and DuVernet (2020) when analysing the gender employment gap, one must examine not only if and how many women eventually secure a job, but also other factors, such as horizontal and vertical segregation, quality of work, gender pay gaps, the so-called “Glass Cliff Phenomenon”, and intersectional forms of oppression. This is important to consider because diverse identity characteristics, such as gender, ethnicity, age, or others may become barriers to accessing the labour market. Hence, women workers with a migrant background, besides being among those who were most impacted by the pandemic, generally face intersectional discrimination at the nexus of gender, race, and/or ethnicity.

The case of South Tyrol

South Tyrol is a wealthy multilingual area that is home to German-speakers, Ladins, Italians, and Roma and Sinti, as well as a growing population with a migration background that is higher than the national average (9.7% compared to the Italian rate of 8.6%). It is a multilingual area where the linguistic rights of the former three main groups are well accommodated, but the latter two remain at the fringes of the society. Among them, women with migrant backgrounds find themselves at the intersection of gendered and racialised structures of oppression while also experiencing other social drivers and external factors that hinder their participation in the labour market.

South Tyrol is a paradigmatic case for manyfold reasons. In the last quarter of 2022, as mentioned, it has registered the highest rate of women’s employment, much higher than the national average. It has a wealthy economy that is mainly based on tourism and agriculture, which in turn implies the need for many seasonal workers. At the same time, gender stereotypes are still very present in society and, in the case of women with migrant backgrounds, are interlinked with episodes of racism. This indicates that, even in rich areas where the gender employment gap is not so wide, gender equality, especially when it is intertwined with intersectional discrimination, is far from being guaranteed. Even local laws and policies, which do address and may have an impact on the equality of opportunities, migration, integration, and gender equality efforts tend to disregard an intersectional approach. This is why this substate unit was one of the two case studies of the project “The Intersection of Gender and Ethnicity in Socioeconomic Participation in South Tyrol and Catalonia in Post-Pandemic Times – InGEPaST”. This project (2022-2023) aimed at unveiling what hinders women and LGBTQIA+ individuals’ socioeconomic participation and intended to promote their access to work, education and other services.

An intersectional lens

An intersectional lens is key to unveiling social inequalities that individuals situated at the nexus of different identity axes—e.g., gender, race, ethnicity, age, disability, class—have to face. The concept of intersectionality, championed by Kimberle Crenshaw in 1989 but also present in other Black feminist writers before her (Patricia Collins, bell hooks), helps to identify patterns of oppression and illustrate how different factors operate and shape each other to form disadvantages and inequalities.

In Europe, intersectional studies have mainly developed around social inequality, identity, power and resistance, and religious diversity by expanding this theory, concept, and methodology that, despite some criticisms, remains promising and fruitful in gender (as well as other) studies. Several academics have tackled the intersection of the so-called “Big Three” (gender, race, and class) regarding access to the labour market. However, there is less research that considers how many other social factors, such as age, disability, gender-based violence, and others, eventually affect employment, and which analyse how they operate at the crucial nexus of gender, race, and/or ethnicity.

The research in South Tyrol

Part of the empirical research of the InGEPaST project, mentioned above, was carried out between April 2022 and January 2023 and explored the intersection of gender, race, and/or ethnicity of women with migrant backgrounds in the domain of work in this substate unit. I conducted 16 qualitative semi-structured interviews with civil society organisations (CSOs) that are based in urban and rural settings in the province of Bolzano. These CSOs were identified based on a purposive sampling strategy and quota sampling. I carried out a web-based search of CSOs that offer assistance or deal with advocacy or awareness raising on gender issues and equality. I identified 29 of these types of CSOs, out of which 26 were invited for an interview. The 16 interviews (in Italian or German) were recorded and then transcribed to be thematically analysed.

Following the InGEPaST project’s approach and methodology, I explain below how this particular intersection works and operates, how it correlates with and differentiates from other social drivers or conditions (e.g., age, class, degree of agency, disability, urban-rural reality), and how external factors (e.g., gender-based violence, prejudices, domestic division of labour, religion) come into play in the case of women with a migrant background. These drivers and factors were identified based on a literature review on gender and work. It should be noted that these results are indicative and not statistically representative. However, they do offer a window into the real-life experiences of women with migrant backgrounds based on the thematic data analysis of the respondents’ perceptions.

What happens in South Tyrol

The women with migrant backgrounds that the InGEPaST project worked with come from different parts of the world, including several African, Latin American, and Eastern European countries. Some of these women have been victims or survivors of gender-based violence, others of human trafficking. Some are trans women who engage in sex work. In some cases, sex work helps to pay the (excessively expensive) rents in South Tyrol’s main urban centres. At the same time, many of the women are willing to learn new languages, find jobs, and show high levels of agency (and bravery).

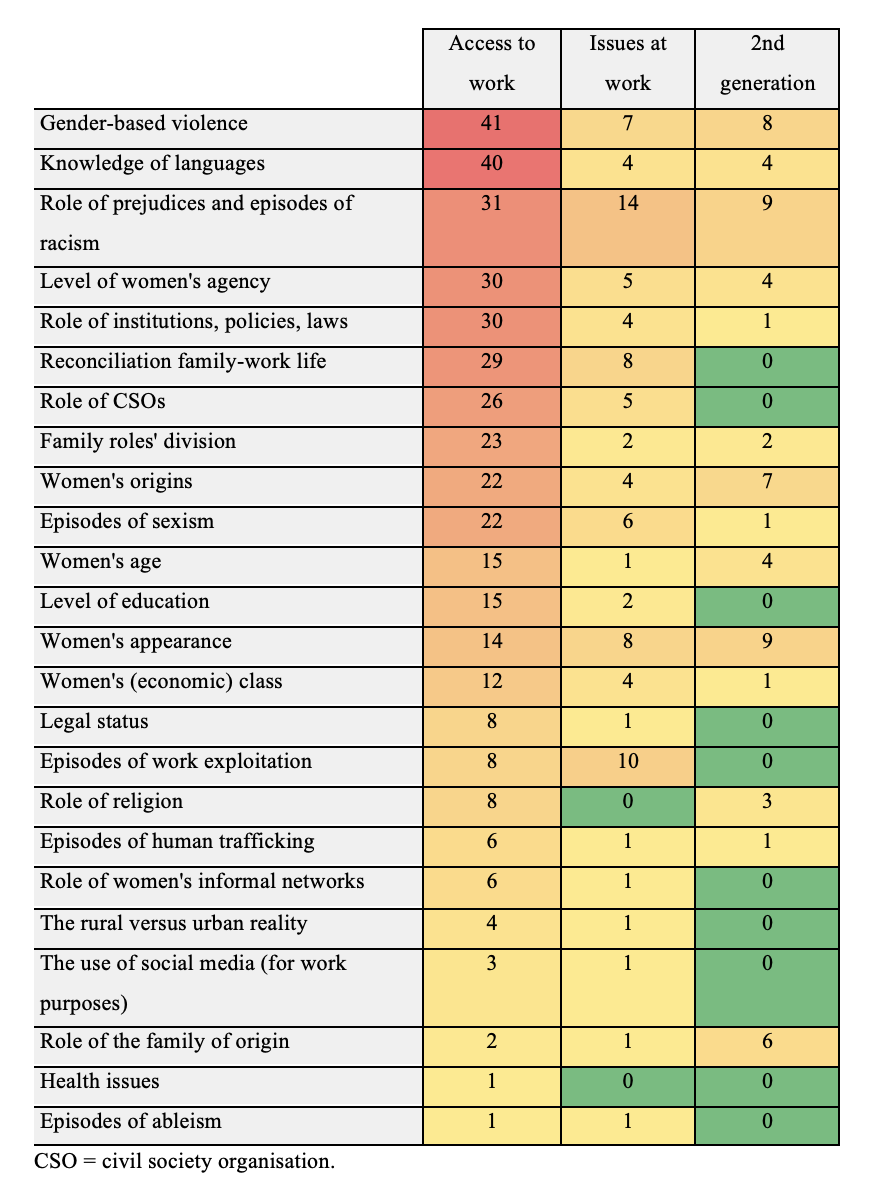

However, they tend to struggle to access the labour market, and, if they do succeed, they face precarity and enter into unsatisfactory contracts. Why does this happen? Thanks to the feature of “matrix coding query” provided by the qualitative research software NVivo-Lumivero, through which the research project’s interviews were coded, it is possible to visualize those social drivers and external factors that have a significant impact on employment. In particular, the correlations that are highlighted in red are those experienced more frequently and are thus likely to be more significant in influencing employment trends.

Table 1: Social drivers and external factors that impact the gender employment gap of women with migrant backgrounds in South Tyrol. Author’s own elaboration through the matrix coding query of NVivo-Lumivero.

Hence, respondents have reported that factors that are most influential in the employment status of migrant women are situations of gender-based violence (GBV); their knowledge of languages, which becomes particularly demanding in multilingual areas such as South Tyrol; the role of prejudices and episodes of racism; their level of agency; the role of institutions, policies, and laws, that can either support or obstruct such access to work; their concerns around family-work life and reconciliation; and their role in the same civil society organisations. For instance, women victims and survivors of GBV must resettle in another part of the province to protect themselves (and their children) from a violent partner. This requires not only a considerable psychological effort but also an extra burden for finding a new job (for personal security reasons) and the added difficulties of balancing work with childcare. Anti-violence canters do help and support them, but they have limited power. Women wearing a veil tend to be excluded during job interviews. Often job offers are made to those with knowledge of both Italian and German, and language learning courses do not always suit their working schedules. Additionally, women with a migrant background are only able to access low-skilled work positions (e.g., in the cleaning sector) that require working hours that do not coincide with those of available childcare services. Other key factors are the division of roles within the family; the country origins of the women; episodes of sexism; and women’s age, level of education, appearance, and (economic) class.

When a job is found, prejudices prevail and they experience many episodes of racism. Many women struggle to manage their significant responsibilities in both their own families and at work, and women’s physical appearance and clothing were shown to play a significant role in their employment experience. Appearances lead to different forms of oppression and exploitation. For instance, if a woman comes from an African state, she tends to face anti-Black racism, while women from Eastern Europe, who are white or whiter, obtain more favourable outcomes in job interviews. Women job applicants are often totally in charge of family care, which hinders their ability to apply for jobs. Many women are often either illiterate or have limited education or digital knowledge. Those with an education are still devalued, including those with a (non-EU) university degree. Also, women with a migrant background in South Tyrol tend to have limited financial resources and come from a low socioeconomic class, which in turn hinders their educational possibilities. Finally, second or first-generation women, those who were born in or who grew up in South Tyrol and who are often educated and bilingual, continue to experience prejudices and episodes of racism. In their case, GBV often materializes in forced marriages, which may take them physically to another country or confine them to their domestic responsibilities.

What’s next

Closing the gender employment gap and specifically addressing the gender pay dimension gap are among the priorities of the EU Gender Quality Strategy for 2020-2025. Equal opportunities in terms of work conditions and career perspectives are core to the EU Pillar of Social Rights action plan. In March 2023, the International Labour Organization launched its Jobs Gap indicator to track the drivers of unemployment and flagged once again how the gender employment gap continues to be crucial.

In South Tyrol, the InGEPaST project’s respondents also suggested creating new opportunities to access the job market, giving priority to those women who experienced gender-based violence and human trafficking; establishing temporary occupations for those without a residence permit while waiting to clarify their legal status; deconstructing prejudices and stereotypes from preschool to the level of local entities and private employers; and changing the paradigm of some occupations’ schedules to accommodate, at best, the need for family and work balance.

At the policy level, another part of this research project has shown that local laws, policies and action plans may be effective tools to enhance gender equality, including better access to the market of women with a migration background. However, they need to be well-designed and, most importantly, duly implemented. In addition, they need to be reformed and apply an intersectional approach, which at the moment is essentially ignored. Currently, these instruments are recreating silos of legal applications and disregarding crucial intersections such as those that women with a migrant background have to face in addition to gender and race.

Alexandra Tomaselli is senior researcher at the Institute for minority rights of Eurac Research, Bolzano-Bozen (Italy) and a former visiting researcher at the Faculty of Legal Sciences, Universitat Rovira i Virgili, Tarragona (Catalunya-Spain). Her research foci include cultural diversity, intersectionality, and human rights. This pitch is part of the research project “The Intersection of Gender and Ethnicity in Socioeconomic Participation in South Tyrol and Catalonia in Post-Pandemic Times (InGEPaST),” which is funded by the Autonomous Province of Bolzano-South Tyrol – Innovation, Research, University and Museums Department (Provincia Autonoma di Bolzano-Alto Adige – Ripartizione Innovazione, Ricerca, Università e Musei).

Alexandra Tomaselli is senior researcher at the Institute for minority rights of Eurac Research, Bolzano-Bozen (Italy) and a former visiting researcher at the Faculty of Legal Sciences, Universitat Rovira i Virgili, Tarragona (Catalunya-Spain). Her research foci include cultural diversity, intersectionality, and human rights. This pitch is part of the research project “The Intersection of Gender and Ethnicity in Socioeconomic Participation in South Tyrol and Catalonia in Post-Pandemic Times (InGEPaST),” which is funded by the Autonomous Province of Bolzano-South Tyrol – Innovation, Research, University and Museums Department (Provincia Autonoma di Bolzano-Alto Adige – Ripartizione Innovazione, Ricerca, Università e Musei).