by Ania Plomien

About a year ago, on February 14th 2023, I read out this letter at a UCU Four Fights strike teach-out. The industrial action for fair pay, sustainable workloads, gender, race and disability equality, and eradicating casualisation ended in September after a months-long marking and assessment boycott. All these struggles remain relevant in the face of persistent economy-wide erosion of wages, as well as multiple inequalities in the higher education sector stemming from workforce casualisation, precarity among early career scholars, representation and ethnicity pay gaps rooted in institutional racism, barriers faced by academics with disabilities, and gendered career progression owing to differences in teaching and teaching-related responsibilities. Ironically, or perhaps inevitably, publishing the letter framed by these struggles and emphasising the need for more time for reading and other worthwhile pursuits, did not meet the cut-off date in time for Valentine’s.

***

I am not sure if I have ever written a love-letter. How to start? How to address you? To call you My Love, My Darling, My One and Only does not have the right ring to it. My Valentine, or better yet, My Funny Valentine? It worked for Paul McCartney[1] and Chet Baker[2], will it work for you? Most apt (of course!) would be A Case of You, since you literally are My Bookcase, and metaphorically, like for the poetess Joni Mitchell[3] ‘you’re in my blood like holy wine’ expressing the emotion of love, but not love-lost.

And so, I’m writing to you with longing for the treasures you hold. For time shared, memories created, friendships forged, and for that which is yet to come. Remember when we first met? In that place called childhood? Nursery rhymes, fairy tales, poems, adventure stories… all moulding a bond so exclusive and intense that I ignored my siblings’ calls to join them in games, pleading, distracting, fighting, then ending in tears. Can such strength of feeling and connection last forever?

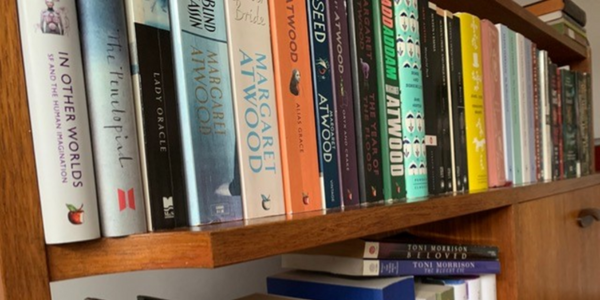

You say love must be nurtured. Like the times when I would not put a novel down until no words were left, racing through the pages towards ‘The End’ and regretting getting there as soon as I did. What happens next? What can possibly come after connecting with the prescient poetic dissections of past, present and future penned by Margaret Atwood? What follows the tapestry of love entanglements on the streets of Alexandria woven by Lawrence Durrell? How would that showpiece on writing, political, emotional and everyday life of Doris Lessing resonate today? Or the profound in its craft and feeling chronicles of slavery and its aftermath composed by Toni Morrison. And John Steinbeck’s heart wrenching explorations of injustice and the lives of migrant agricultural workers, all controversial for their sharp critique of capitalism, racism, sexism and all other kinds of inequalities.

So, as I said, what can possibly follow this? There is laundry, and getting groceries, and dusting, and yes, getting back to my PhD… It seemed, back then, that only housework can compete with the pleasure of reading. But no amount of dust-bunnies or piles of laundry can free time for guilt-free reading. Leisure time, housework time, care time (for self and others), and of course time for politics in our turbulent present with its tendencies to divide and atomise – all that time has shrunk. Do I pack a book for a train journey that is just for me? Shouldn’t I bring that stack of articles I set aside to update the reading list instead? The paper I agreed to review? The PhD chapter that needs feedback? That new university policy draft requiring input. The reference letter for the student from three years back? Even when I decide to switch off and pack a novel on holiday, there is the unfinished conference paper that will be given right after the break (can I get-away with slides only?). The MSc dissertation extension requests need to be approved (it is the new August). And the dissertations submitted on time, which should be marked before induction week.

How about work books? Those by the giants on whose shoulders we are meant to stand. Or new books by colleagues, in my field and others. Are these now out of time-bounds too?

Photo Credit: Part of the author’s own bookshelf

This brings me to that annoying thing, The Inbox, a pesky little thing, accordion like, infinitely elastic – stretches as soon as you attempt to shrink it. I totally fell for the myth of shrinking The Inbox. Tried shrinking in the morning, shrinking in the evening, shrinking in the afternoon. Nothing works! Approaching Inbox-shrinking like training for a half-marathon – systematically gaining strength, speed and endurance… all to no effect. In the end, I checked the label, a legalese/techy small print: Shrink proof. Made of non-shrinkable technology. No matter what and how much you try, The Inbox cannot be shrunk.

This is not a ‘me’ problem. One example is the long hours and work intensification common to many workplaces, including academia, where being an academic is not a 9–5 job. Accordingly, structural change in higher education, brought about by the sector’s marketisation, the commodification of learning and the growth of managerialism, induced performance measurement, surveillance and bureaucratic control, diminished opportunities for exercising academic freedom and autonomy, and spurred quantification of academic output. In this context, levels of psychological distress among UK academics are reported to be above other professionals, with only 38% coping with their job demands, making it difficult to fulfil both working and non-work roles. Research conducted in the Nordic countries, resonating with patterns in the UK, points to the phenomenon of work-work balance, wherein higher education workers confront conflicting simultaneous demands of their jobs, as they are split across different tasks, multiple projects, functional roles.

The second example is the amount of pro-bono work, not just the invisible labour done within and for the institution, but labour for society more widely. A 2017 analysis of UK academics’ public engagement and knowledge exchange has shown that UK university staff delivered over 40 million hours of such work, equivalent to 24,493 full time jobs. The economic value of these activities was estimated at £3.2 billion per year (compare collaborative research, consultancy, continuing professional development contracts held by the UK universities at £4.2billion). Anyone working in the higher education sector can relate to feeling ‘encouraged’ to provide such public service and knowledge exchange to society, which amounts to an enormous and economically significant volume.

Any decline in collegiality must be interpreted in the long working hours, mounting pressures, and demonstrable ‘relevance to society’ context. A few years ago, I agreed to referee a best paper competition in an interdisciplinary field. I spent a week reading, ranking, then discussing the submissions, the finalists and the winners. I read a lot, I learned a lot, I was intellectually pushed. This being one of the best intrinsic rewards of the job – I loved it. The following year, I and my counter-referee were asked to do this again, since we have done such an excellent job (of course we did!). We both declined the invitation.

——

My Funny Valentine, you say ‘don’t bring work into this’. But that is another fantasy. I know you’ll agree, just look at the contents of your shelves! Can there be any clear separation between ‘work’ and ‘non-work’? I am talking about time as much as about content. The literary themes of poverty, precarity, dispossession, capitalism, revolution and justice are all about life-work. Even the self-indulgent series with two octogenarian detectives roaming the streets (and pubs) of London to solve ‘peculiar’ crimes are about the state and the state of things. My ‘work’ sources too are about the stuff ‘life’ is made of. So many treasures – Angela Davies, Nancy Fraser, Maria Mies, Anne Phillips, Iris Marion Young, and then Antonio Gramsci, Karl Marx, Amartya Sen… the list goes on.

This Letter of Longing is also a Letter of Affirmation and Celebration, my top 10, top 50… top 1,000 reads? Where to start? With a revolution, of course, on a daily basis, and so a quote from Rosa Luxembourg ‘The world-historical advance of the proletariat to its victory is a process (…), the masses of the people themselves, against all ruling classes, are expressing their will. But this will can only be realised outside of and beyond the present society. On the other hand, this will can only develop in the daily struggle with the established order, thus, only within its framework.’ Drawing attention to the fight for minimum demands, the overturning of power, and the limits of reform. Crucially, the feminist academic who longs to read more (fiction and non-fiction) chimes in with Susan Ferguson to ‘collectively insist on putting need over profit by demanding that the resources for social reproduction be expanded – who attempt, that is, to take life back from capital (…) [M]anaged to a large degree by the state, the fight against capital must also engage the state – through attempts to assert the priorities of life over capital whether in paid or unpaid sites (… ) [P]rioritising building bridges between multiple fronts, figuring out ways for workplace strikes to incorporate anti-oppression politics and for anti-oppression strikes to incorporate workplace-based demands (…) [E]ngender social bonds to counter the alienation and isolation of capitalist subjectivity inherent in the very act of organising with others to improve control over the conditions of work and life.’

The collective insistence necessarily joins all the struggles together – casualisation is as much of a concern to a mid-career academic as a gender and ethnicity representation gap to her precariously employed or early career (not necessarily the same) colleague. This necessity for the ‘control over the conditions of work and life’ is what keeps solidarity and the love of reading going. Our ‘At Last’ moment, so beautifully rendered by Etta James[4], will not arrive without solidarity and struggle.

Dr Ania Plomien is Associate Professor at the Department of Gender Studies, London School of Economics & Political Science. Her research concerns social reproduction theory and analysis of the paid and unpaid work nexus, employment, care, and labour migration in the context of the European Union, the United Kingdom, Poland and Ukraine.

Dr Ania Plomien is Associate Professor at the Department of Gender Studies, London School of Economics & Political Science. Her research concerns social reproduction theory and analysis of the paid and unpaid work nexus, employment, care, and labour migration in the context of the European Union, the United Kingdom, Poland and Ukraine.

[1] Paul McCartney (2012) ‘My Valentine’, Kisses on the Bottom, Hear Music.

[2] Chet Baker (1954) ‘My Funny Valentine’, Chet Baker Sings, Pacific Jazz Records.

[3] Joni Mitchell (1971) ‘A Case of You’, Blue, Reprise Records.

[4] Etta James (1960) ‘At Last’, At Last, Argo Records.