by Nicole Bourbonnais

“Where are the women?” When Cynthia Enloe posed this question in 1989, she was thinking about the world of international politics. But the question has also been a driving force for a number of historians who have sought to move beyond the narratives of “great men” that have tended to dominate our understanding of the past. In honour of Women’s History Month, this post outlines some of the central principles and shifts in the practice of women’s history, with some examples from my own field, the history of birth control and reproductive politics.

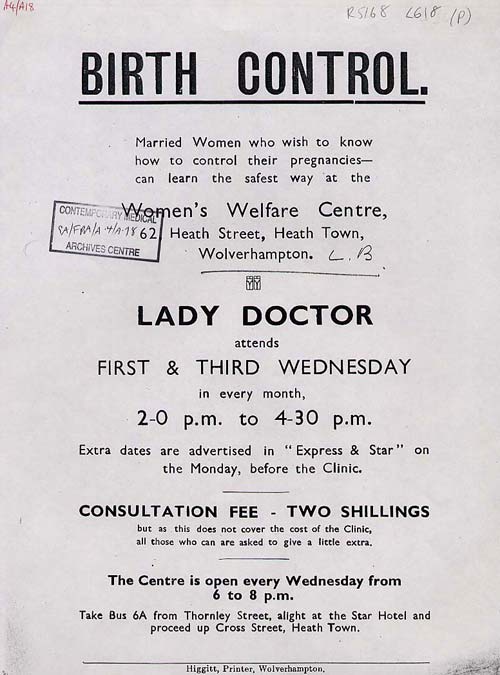

Although documentation of women in history stretches back much further, the feminist mobilization of the 1960s and 70s provided an undeniable impetus to the field of women’s history. Women’s historians during these years outlined a dual project: to restore women to history and history to women. The first entailed recognizing the critical (if usually unrecognized) roles women had played in the key events that dominated historical studies and nationalist narratives: high politics, wars, revolutions, social movements. They wrote histories not only of the more visible actors (the Joan of Arcs, the Sylvia Pankhursts), but also of the peasant women who led marches during the French Revolution and the women who fought in the Algerian War of Independence. But scholars also argued that since much of women’s experience had taken place outside the public realm, a focus solely on women’s activism in these spheres could not tell us the whole story. They thus expanded the limits of historical inquiry into the so-called “private sphere,” writing histories of the family, histories of birth control, histories of childbearing and child raising.

In doing so, they challenged us to rethink what counted as historically significant. Take the period from the end of WWII to the 1990s, for example. In many historical accounts (the kind we get in textbooks) the focus would likely revolve around the high politics of the “Cold War,” outlining the threats exchanged between American and Soviet leaders and the ideological battle between capitalism and communism… critical issues, no doubt. But what if we shift our position to start with women, and/or the home? We might come to also see the incredible power of new technologies like the birth control pill and shifting cultural mores that led to rapid declines in family size in many countries, altering sexual practices and paving the way for increased women’s participation in the workforce. While these processes are not as easy to document as the chronology of Cold War confrontations, for many they may have impacted daily life as much as (if not more than) the grandstanding of political leaders.

In drawing our attention to the world beyond high politics, women’s historians were part of a broader group of “social historians” who argued that the social and cultural practices we take for granted in fact have a history, and one which we need to understand. But women’s historians brought a feminist perspective to this field, which led them to think more critically about the power relations that shaped the domestic sphere while also searching actively for women’s voices in written sources and beyond. Indeed, while some “family historians” continued to write about families as benign (if evolving) units or reduced the demographic change noted above to statistical analysis, women’s historians unearthed the reality of violence and inequality within households and collected oral histories that captured not only the changes in women’s lives, but their thoughts and experiences surrounding these shifting dynamics [1].

Heeding the feminist principle that “the personal is political,” women’s historians also recognized early on that if the private sphere was interesting in its own right, it was rarely disconnected entirely from the public or political sphere. Thus, women’s historians paid keen attention to the ways political controversies and state policies shaped women’s intimate lives, and how their actions in turn could stir up political controversy and drive policy-making. This forces us to think harder, for example, about the connections between things like the Cold War and access to birth control; indeed, the massive influx of Western aid for family planning programs internationally in the post-WWII period was driven in part by fears that population growth abroad would lead to destabilization in decolonizing countries and a turn to communism. Women’s use or non-use of birth control could thus take on geo-political implications. Starting with a drive to explore “women’s experience” thus allows us not only to see new spheres of interest, but also to see new dimensions of old spheres of interest.

But the effort to uncover “women’s experience” also unearths a number of tensions. Perhaps most obviously, “women” do not make up a homogenous or coherent category. As decades of scholarship have shown, women’s experiences are profoundly shaped not only by their “femaleness”, but also by categories of race, class, nation, sexual orientation, age, and more. The history of birth control, again, provides an illustrative example of this fact, for if the introduction of new contraceptives was emancipatory for some women in the 20th century, it left a more complicated legacy for others. Racist and classist eugenic policies fuelled the compulsory sterilization of thousands of poor and ethnically marginalized women in the United States (and, most infamously, Nazi Germany), while women in “developing countries” became test subjects for new contraceptives at times without their explicit consent. In other countries, even voluntary birth control remained (remains) inaccessible, kept out of reach as a result of financial, religious, or cultural barriers. The experiences of some women, then, cannot stand in for all; when we slip into this, we present a skewed understanding of the past that can fuel misguided strategies in the present.

In more recent decades, gender theorists have also worked to destabilize the very idea of “woman” having a biologically-based stability that could be “recovered” unproblematically, calling on historians to think more critically about gender as a relational category and the construction of “femininity,” “masculinity” and sexuality over time. This perspective is outlined most famously in Joan Scott’s “Gender: A Useful Category of Historical Analysis”. For some historians, this shift seemed potentially troubling: would a focus on deconstruction of cultural and social texts lead us to abandon altogether the very real actors driving historical change, and the emancipatory methods of women’s history? Some gender histories have, indeed, put aside the task of “restoring women to history,” focusing instead on providing insightful take-downs of gender norms and binaries and illustrating the fluidity of gender, sexuality, and the body across time and space. But others have seen deconstruction as a tool rather than a goal [2], as a way to better contextualize and provide more sophisticated analysis of the way social and cultural ideologies have shaped the experiences of women, men, and everyone who falls in between or outside these categories. Indeed, the rise of gender history has pushed historians to think more critically about the way gender shapes society as a whole. In my own research it has been stimulating to explore, for example, how mid-20th century birth control policies – even when nominally targeted solely at women – were guided under the surface by ideas about masculinity, sexuality, and the family, with broad-reaching implications. Recognizing this, I would argue, is critical not only to understanding women’s experiences in the past, but also to our efforts to design and promote policies in the present that promote reproductive justice for all.

Today, it might be less common to hear someone describe themselves as practicing “women’s history” with the sense of focused purpose one might have had in the 1960s. Many of us find it difficult to isolate out “women’s experience” and end up drawing on a range of traditions and theories, while moving amongst a variety of academic communities. But in doing so we should not lose sight of the critical insights of the last half-century of women’s history: the recognition of the intricate links between the personal and political; the constant attention to power relations in all spheres; the awareness of interlocking systems of domination; and the essential commitment to always look for women and listen to them whenever and wherever we can.

Often, writing this history can be depressing, revealing the incredible resilience of various gender norms and the destructive legacy of sexism, racism, and imperialism. But one also comes across incredible moments of inspiration: when individuals transcended the discourses of their time to articulate analysis of their situation that still seem profound today; when groups of people mobilized to force change; when politicians moved past partisan squabbling and faced controversial topics head on; when people’s actions in informal spaces led to cultural revolutions that could not be contained by political paralysis or retrograde laws. These moments can provide some practical guidance and rhetorical tools for contemporary struggles. Above all, they show us how dramatically things can change; they have in the past, and they can in the future.

[1] On the continuing tension between family history and women’s/gender history, see Megan Doolittle, “Close Relations? Bringing Together Gender and Family in English History,” Gender & History Vol. 11 No. 3 (Nov 1999): 542-554. On the use of oral history see Joanna Bornat & Hanna Diamond, “Women’s History and Oral History: developments and debates,” Women’s History Review 16:1 (2007): 19-39.

[2] For this distinction, see Florencia E. Mallon, “The Promise and Dilemma of Subaltern Studies: Perspectives from Latin America,” American Historical Review, 99.5 (1994): 1498.

Dr Nicole Bourbonnais is an Assistant Professor of International History at the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies in Geneva, Switzerland. Her research focuses on the rise of birth control campaigns, population control policies, and reproductive rights activism in the twentieth century.