by Nour Almazidi

The institutional and epistemic marginalisation of Gender Studies as a legitimate academic discipline in the Gulf region raises several theoretical and political questions around power relations in knowledge production, the disciplinary parameters of knowledge, the valuable disruptions of feminist pedagogy, and the transformative potential for change that is present within feminist epistemology.

As it currently stands, no universities in the Gulf region offer a stand-alone degree in Gender Studies. There are, however, two universities, Hamad Bin Khalifa University in Qatar and Zayed University in the United Arab Emirates that offer graduate degrees on Women, Society, and Development and Muslim Women’s Studies respectively. The American University of Sharjah also offers a minor in Women’s Studies. As for coursework, Qatar University’s Department of International Affairs has four undergraduate courses related to Gender Studies: Women and Islam, Gender in International Perspective, Women and Violence, and Gender in Law. (Alsahi, 2018, p.2). While gender research and scholarship continue to proliferate in various forms in the Gulf, particularly under social sciences and humanities departments, Gender Studies as an interdisciplinary academic field itself is faced with challenges to its recognition, legitimacy and visibility. The marginalisation of Gender Studies is not only shaped by a lack of willingness to introduce new fields in academia, but also by a broader context of socio-political, religious, and patriarchal resistance to the kinds of knowledges and interventions produced by feminist discourse and gender critiques.

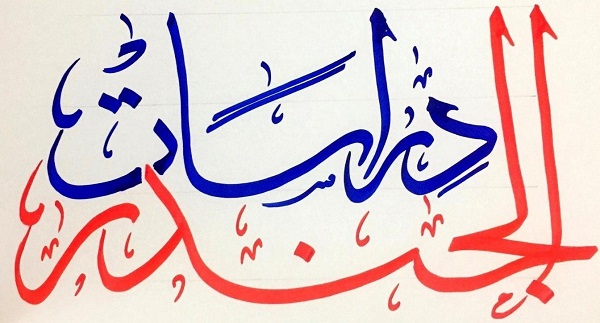

Picture of “Gender Studies” written in Arabic by the author’s father, Hesham Almazidi.

The emerging scholarship on gender and sexuality in the Middle East is rich and meaningful in its interventions into queer theory, women’s rights, critiques of male dominance over religious knowledge production, and reconfigurations of the relationship between gender, sexuality and Islam. One of the most salient features of Middle Eastern feminist scholarship is its engagement with local debates, and its insistence on remaining attuned to the specificities of historical, political, and social contexts. (Abu-Lughod, 2002; Mahmood, 2005; Najmabadi, 2005; Kandiyoti, 1996; Al-Samman & El-Ariss, 2013). In the context of the Gulf region, it is precisely these interventions into ‘taboo’ subjects, such as Islamic interpretations of women’s roles, discourse on non-normative sexualities, gendered citizenship, and oppressive legislations, that pose a ‘danger’ and thus constitute a challenge to the institutionalisation of Gender Studies.

Gulf universities are spaces that already need to be navigated with care, given the present restrictions to ‘academic freedom’ posed by a governmental top-down control of academic discourse. (Nasser & Romanowski, 2010; Uddin, 2009). In a foreword to Gayatri Spivak’s In Other Worlds, MacCabe (1987) notes that when attempting to realize an educational project embedded in transformative politics, “the problem is neither the micro-political conservatism of any institution nor the genuine problem of elaborating an educational programme which emphasized both individual specificity and public competence. It is that such a project will encounter powerful macro-political resistance” (MacCabe, 1987, p.xviii), a reality that is evident in current attempts at creating spaces for Gender Studies in Gulf universities. An example of such resistance is the institutional and societal backlash received by Dr. Hatoon Al-Fassi, a Saudi academic at Qatar University, when she was scheduled to debate a male professor from the university’s Sharia College to discuss the topic of women and Islam. The debate was followed by heavy criticism of al-Fassi for supporting an article that argues that Qatar did not grant women their full rights, and criticisms of the content of her previous syllabi for the Women and Islam course. Al-Fassi’s Women and Islam course engaged critical feminist approaches to religious texts whereby “students were encouraged to choose one Quranic verse that talks about women’s rights in Islam, and then read various interpretations of that same verse ranging from the 9th century Muslim historian al-Tabari to the mid-20th century leading Islamic theorist Sayyid Qutb. This comparison was aimed at making students critical of the ways in which Islamic ideals have been translated into our contemporary laws and practices, and that many patriarchal discourses were incorrectly attributed to Islam itself.” (Alsahi, 2018, pp.2-3). The consequences of such heavy criticism led the University to cancel the scheduled debate. Al-Fassi was also subjected to surveillance and was eventually barred from teaching the Women and Islam course.

Such forms of opposition do not only arise when religious discourses and interpretations are under scrutiny. The categorization of feminist knowledge, gender theories, and feminism more broadly as a Western, colonial and imperialist import continue to inform the marginalisation of Gender Studies. Leila Ahmed (1992) argues that the links between feminism and colonialism emerge from a Western colonialist promotion of feminist discourse within the colonized Arab countries, particularly in Egypt, and have thus resulted in its dismissal. But to reduce feminist discourse, and consequently Gender Studies to a product of colonial and imperialist frameworks would be to align oneself with a politics of origins that ignores Arab women’s movements throughout history, as well as the valuable interventions of postcolonial feminisms and articulations of Arab anti-colonial feminist thinking. Postcolonial feminism’s critiques of the homogenising imperialist essentialism and discursive colonial analytical techniques found in Western feminist scholarship on Third World women disrupts uniformed understandings of Third World patriarchy and male dominance. Indeed, post-colonial feminist contributions have played an essential role in laying bare the complex interactions of gender, race, ethnicity, sexuality and class in constituting women’s lives and political struggles. Such critiques have also addressed the failure to produce systemic analyses of the ways in which power operates with a broader examination of the continuously changing historical and cultural specificities that inform the Third World subject, and further deepened our understandings of coloniality, subalternity, orientalism, representations, and agency (Mohanty, 1988; Spivak, 1988; Lugones, 2010; Said, 1979, Quijano, 2000; Mahmood, 2005).

The establishment of Gender Studies in the Gulf marks the possibility of introducing a new set of epistemic interventions that move away from a focus on monolithic representation and Othering discourses on Arab women towards a fuller engagement with socio-economic, political and historicised accounts and understandings of systemic power relations at the local and transnational level. Furthermore, it offers a platform to engage with existing conversations within Middle Eastern scholarship on gender and sexuality while simultaneously bridging the gap in social sciences scholarship focused on the Gulf region, and making valuable contributions to transnational conversations around interdisciplinary subjects. It is through a cultivation of engagements with “scattered hegemonies” (Grewal & Kaplan, 1994, pp.7-17), modern formulations of biopolitics that are increasingly being sketched out, governmentality, gendered citizenship, articulations of political agency, rights cultures and vocabularies, understandings of nationalism, migration, statelessness, and re-articulations of the relationship between gender and religion that Gulf Gender Studies can make its most valuable interventions. Recognising Gender Studies also holds the potential of disrupting narratives of unidirectional transnational cultural, political, and economic flows by redefining Gulf countries as producers of knowledge, rather than its subjects.

While Gender Studies is still in its foundational beginnings in the Gulf region, it is important to address questions around the centrality of the discipline to broader scholarships and the importance of a gender perspective within, for example, the study of international relations and global politics. Current understandings of Gender Studies relegate it to the epistemic margins as the field is deemed irrelevant or considered a discipline that only pertains to ‘women’s issues’. This primarily suggests a failure to take into account how the study of gender has provided deeper analyses of normative understandings of social processes as a whole, and how it continues to shed light on the workings of power, knowledge, institutions, and structures. Feminist theory’s interventions have also reshaped research engagements in social sciences through its critiques of “existing fantasies of objective knowledge produced by autonomous subjects” (Hemmings, 2012).

The marginalisation of Gender Studies as a legitimate knowledge producing discipline prompts questions around the politics of knowledge production: who gets to be ‘known’ and who gets to be the ‘knower’? This matters because, as mentioned, knowledge is not neutral, but power-imbued and value laden, and as Sumi Madhok reminds us, “feminist epistemology is deeply invested in the transformation of existing inequitable societal relations.” (Madhok, 2014, p.2). Knowledge produces change, and feminist knowledge declares its investment in transformative politics that holds the potential of creating new epistemic insights, conceptual contributions and vocabularies for social movements of change in the Gulf.

As a Kuwaiti Gender Studies student in a Western academic institution, much of what I have been concerned with has been an insistence on considering the different genealogies of sex/gender/sexuality in a Middle Eastern context, and the importance of ‘doing the work’ when it comes to the linguistic contours of sex/gender/sexuality and their different epistemological resonances that do not necessarily follow a Western conceptual terrain. I am hopeful that when Gender Studies are to be recognised in the Gulf region, there would be not only valuable interventions into understandings of meanings of sex/gender/sexuality in a Khaleeji context but also deeper analyses of the complexities of writing in Arabic on gender, sexuality and feminism as it would provide the space and opportunity to join current conversations in Middle Eastern scholarship on the weight of translation, meaning-making, and knowledge production when it comes to creating new Arabic terminologies within Gender Studies.

This blog post is part of a series of posts on transnational anti-gender politics jointly called by the LSE Department of Gender Studies and Engenderings with the aim of discussing how we can make sense of and resist the current attacks on gender studies, ‘gender ideology’ and individuals working within the field.

Nour Almazidi is an MSc Gender alumna of the LSE Department of Gender Studies. She holds a BA in International Relations and Political Science from the University of Birmingham and her work focuses on transnational feminist and queer political theory and activism. She can be found on Twitter @nuralmazidi

Nour Almazidi is an MSc Gender alumna of the LSE Department of Gender Studies. She holds a BA in International Relations and Political Science from the University of Birmingham and her work focuses on transnational feminist and queer political theory and activism. She can be found on Twitter @nuralmazidi

We live in a very messed up society

what a messed up society