by Selin Çağatay

The current decade has seen popular mobilizations against gender equality in Europe and globally. In Turkey, this process is led by the Justice and Development Party (AKP) and mediated through authoritarian and populist ways of governing, institutionalized Islamism and Sunni-Turkish nationalism. Dynamics of Turkey’s gender politics are somewhat different than those identified by scholars who examine transnational anti-gender movements. Yet, looking at the Turkish case might help us to better understand different, seemingly unrelated contexts as varieties of a global trend against gender equality and critical research that explores gender as a socio-historical construct.

Targeting gender equality without targeting gender studies

Instead of an outright attack on gender studies, AKP governments have so far sought tacit exclusion of feminist and queer researchers as part of a larger onslaught on academics who express opposing views on Turkey’s regime change under Tayyip Erdoğan’s leadership. Specifically, there are a significant number of feminist and queer academics among those who were purged, forced to retire, or simply intimidated out of their posts after signing the petition for the peaceful resolution of the state-led war in Kurdish-populated provinces in southeast Turkey. This makes questionable the sustainability of critical gender research despite the absence of a ban on gender studies. Needless to say, those who still keep their posts are pacified into self-censorship.

Persecuting academic research and expression is just one aspect of the nationalist crackdown on civil society that started after the Gezi-inspired protests of 2013, intensified by the Syrian war and the termination of the peace process with Kurds, and became full-fledged in the aftermath of the failed coup d’état in 2016. Increasingly, persons or organizations who criticize AKP’s politics are labelled as “terrorists” and face various forms of persecution. Following the failed coup, feminist journalists, intellectuals, activists got arrested. Kurdish feminists received a disproportionate share of state violence—a clear indication of how anti-feminism intertwines with nationalism; politicians (including MPs) were jailed, numerous women’s organizations and news agencies were shut down. LGBTI rights activism was silenced with the argument of it being an “offense against public morality”. These developments weakened the relationship—a crucial one for critical gender research—between feminist and queer activism and academia.

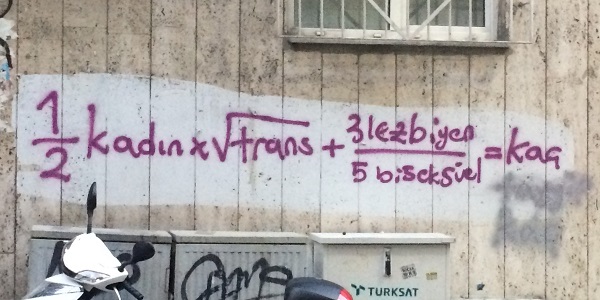

Photo taken by the author: Graffiti in response to Erdoğan’s depiction of childless women as “deficient, incomplete”.

Debilitation of feminist and queer activism and academia makes it easier for AKP governments to gather consent for their counter-narration of gender as a God-given purpose of creation. Yet, this can be the tip of the iceberg when we consider how dramatically changes in the education system and social policy jeopardize gender equality. In the past several years, notions such as gender complementarity and purpose of creation (fıtrat) have entered the school curricula at all levels as state sources were channelled from secular to religious education. Family-oriented strategies in social policy have designated the family as the site where the care needs of children, elderly and disabled are met and only then included women in paid work on flexible, low-paid, insecure terms. Numerous protocols signed between the Directorate of Religious Affairs (i.e. the locomotive of state-imposed religion) and other state institutions, notably the Ministry of Family, Labour and Social Services (State Ministry for Women’s and Family Affairs until 2011—note the erasure of “women” in the title), made sure that institutionalized Islam has a key role in reframing social relations, including gender, in a way that naturalizes inequality.

Better than the “West”

Developments like these are seen in contexts as diverse as Russia, Brazil and a number of EU countries where anti-gender mobilizations are backed by the rise of regimes, characterized variedly as authoritarian, illiberal, right-wing populist etc., that simultaneously deepen inequalities based on class, race, ethnicity and religion alongside gender and sexuality. But why hasn’t the AKP, like Fidesz of Hungary, annulled critical research on gender altogether, or at least launched a smear campaign against it? One reason could be that gender is largely understood as relations between men and women instead of that between people of different gender identities. Feminist intellectuals in the late-1980s translated the concept of gender to Turkish, a language with no gender pronouns, as “social sex”. The term social sex entered the academic jargon rather smoothly and did not spark much controversy in public debate. Nonetheless, gender studies programs often carry the title “women’s studies” and only to a limited extent problematize the visibility and legal rights enjoyed by LGBTI people in Turkey compared to, say, EU countries.

Yet, a more plausible reason is Turkey’s positioning vis-à-vis the “West” as an imagined as well as experienced locus of political modernity. The Islamist elite argue that the secular westernist elite betrayed their Islamic roots and oppressed believers with top-down modernization policies. That cultural westernization degenerated Turkish women, destroyed the true Turkish family, and brought immorality to Turkish society. By portraying Turkey increasingly as not-Europe the AKP feeds neo-Ottomanist aspirations of being a dominant player in the Middle East and mobilizes support for a Sunni-Turkish nationalism where Turkey is an alternative civilizational centre to Europe. At the same time there is a third worldist, anti-imperialist component of Turkish nationalism, secularist or Islamist, which comes with the claim of being better, more advanced, ahead of Europe when it comes to women’s status in society. Thus, there is not a direct challenge to gender studies per se but the argument that gender justice is qualitatively better than the universalist notion of equality “imposed by the West”. Blending postcolonial theory’s critique of western hegemony with Quranic verses in a dodgy manner, the gender justice approach seeks to integrate women in modern life without coming into conflict with their “inherent characteristics”, understood as their duty of motherhood. It thereby seeks to eliminate the suffering of women caused by the “struggle for equality with men in order to achieve the same level [sic] in a system designed for men”.

Appropriation of feminist concepts

Therefore, for example, the Turkish Higher Education Council has recently issued a policy document, on the occasion of March 8th, based on which public as well as private universities were able to establish structures to prevent sexual harassment on campus, and introduce university-wide compulsory courses on gender. Compare this to Hungary where family studies replace gender studies. This means, even in cases where gender studies is kept untouched we still need to ask: what kind of gender research? In the past few years pro-government women’s organizations (GONGOs) as well as state institutions have collaborated with Turkish universities in organizing events, particularly on the occasions of November 25th and March 8th, where parties appropriate feminist concepts such as empowerment and agency and employ them to legitimize their counter-narration on gender. This also helps them to secure funding from the EU and other donors to implement and sustain anti-egalitarian gender politics. Meanwhile, feminists’ November 25th demonstration this year faced police intervention and conveniently got discredited.

Take also the example of gender-based violence. The Islamist elite define violence against women as betrayal to humanity and embrace the UN Women agenda for eliminating violence. Turkey is proud to be the first signatory of the Istanbul Convention notwithstanding the flaws in implementation. Again, compare this to governments in Hungary or Bulgaria who won’t ratify the Convention because it contains, in their view, radical feminist ideas they cannot endorse and discriminates against men by portraying women as victims and men as oppressors. Yet, pro-family policies in Turkey are a serious obstacle before eliminating gender-based violence because they preclude women’s independence from the perpetrator of violence.

Decentring anti-gender mobilizations

Feminist analyses of anti-gender mobilizations have so far focused almost exclusively on Europe and the Americas—the Christian- and/or white-majority part of the world—and on campaigns supported or led by the Vatican or churches of different denominations. It is true that protests against the very term “gender” have been largely contained within certain geographic, cultural and religious borders where political actors claim modernity as authentically their own framing them variedly as being European or Christian or western. Yet, limiting the scope of analysis to these borders would perpetuate their prioritization over the rest of the world. It would make invisible the relationality between western and non-western imaginations and experiences, and eventually strengthen the hand of those for whom opposing “gender ideology” is part of demarcating borders. Mobilizations against gender equality go beyond the “West” and include, for example, waves of political violence against women’s rights activists and critical social scientists in the Middle East region after the so-called Arab spring. Decentring our analysis by integrating in the discussion ‘non-western’ and ‘non-Christian’ contexts such as Turkey where activists, academics and institutions advocating gender equality are under threat would help to vernacularize existing knowledge while forging global frames of analysis in relation to imperialism, neoliberalism, and heteronormative patriarchy.

Two lines of inquiry are crucial here. First is to expand the analytic focus on the discursive framing of anti-gender mobilizations to involve changing aspects of institutional settings, budgeting and social policy as well as state-civil society relations that facilitate regime transformation. This way we can investigate how, from an intersectional perspective, inherently inegalitarian social engineering programs based on class, racial/ethnic or religious differences complement mobilizations against gender equality in each context.

Second is to trace the historical development of local formations that oppose gender equality from a transnational perspective. Feminist scholars have been documenting the loss of momentum in the implementation of the global gender equality agenda already since the early 2000s. Among the reasons they identified is the global rise of religious forces that recruited all over the world those sections of societies that suffered from neoliberalism the most. We need to be able to show, for instance, when Turkish GONGOs claim that the notion of gender justice is superior to the western notion of gender equality and more compatible with Turkish-Islamic culture, that gender justice was exactly what Catholic Vatican hand in hand with Shia Iran wanted to replace gender equality with at the UN conferences of the 1990s. Locating local gender politics as regards the world hegemonic order would, in return, allow us to re-conceptualize as historical co-construction and thereby destabilize binary discourses on gender such as western vs. non-western, modern vs. traditional, democratic vs. authoritarian, liberal vs. illiberal, Islamophobic vs. Islamist—varieties of “us” and “them”. Such an endeavour is necessary if we are to build transnational solidarity to resist the backsliding in gender politics.

An earlier version of this blog post was presented on 16 November 2018 at the panel “Speaking back to the backlash – research and resistance” organized by the Department of Gender Studies at Lund University, Sweden. This blog post is part of a series of posts on transnational anti-gender politics jointly called by the LSE Department of Gender Studies and Engenderings with the aim of discussing how we can make sense of and resist the current attacks on gender studies, ‘gender ideology’ and individuals working within the field.

Selin Çağatay is a postdoctoral fellow in gender studies at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden. She is involved in the research project Spaces of resistance. A study of gender and sexualities in times of transformation. Her research interests include women’s and feminist activism, gender regimes, intersectionality studies, NGOs, secularism, Turkish political history, and women’s paid and unpaid labor. She has lectured at Central European University and Eötvös Lorand University in Budapest, Hungary. Her latest article “Women’s Coalitions beyond the Laicism–Islamism Divide in Turkey: Towards an Inclusive Struggle for Gender Equality?” appeared in Social Inclusion. Selin is a feminist activist affiliated with Çatlak Zemin and Kadınlar Birlikte Güçlü in Turkey.

Selin Çağatay is a postdoctoral fellow in gender studies at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden. She is involved in the research project Spaces of resistance. A study of gender and sexualities in times of transformation. Her research interests include women’s and feminist activism, gender regimes, intersectionality studies, NGOs, secularism, Turkish political history, and women’s paid and unpaid labor. She has lectured at Central European University and Eötvös Lorand University in Budapest, Hungary. Her latest article “Women’s Coalitions beyond the Laicism–Islamism Divide in Turkey: Towards an Inclusive Struggle for Gender Equality?” appeared in Social Inclusion. Selin is a feminist activist affiliated with Çatlak Zemin and Kadınlar Birlikte Güçlü in Turkey.