by Senel Wanniarachchi

Each year students on the LSE Gender MSc course Sexuality, Gender and Globalisation present independent research papers at an all-day student conference. This year’s conference “Globalising Desire / Locating Power” took place on 29 March 2019 and in this series of posts a selection of students present their interventions from the conference.

In October 2018, Sri Lankan President Maithripala Sirisena unconstitutionally appointed former President Mahinda Rajapaksa as Prime Minister. However, the Incumbent Ranil Wickramasinghe refused to step down, resulting in the grotesque situation of the island having two concurrent ‘Prime Ministers’. While Sirisena offered different justifications for this flagrant breach of the constitution, one which he announced at a large political rally in the capital of Colombo was that Wickramasinghe was ‘a butterfly’ and that his close circle of confidantes were all ‘butterflies’. ‘Samanalaya’ or butterfly is a pejorative slur used to mock queer people by the Sinhala language speaking majority in the Sri Lankan island. The term is usually deployed to refer to a certain type of a queer person — often a man and an ‘effeminate’ man.

What kind of affects does this statement by the President permeate on the bodies of his listening subjects and the body politic of the nation? What sensations are triggered in mind and the viscera of the listener as these words hit their flesh and the electric signals of these words are interpreted by their brains? What about their bodies remains the same? What is changed, for whom and in what ways?

Butterfly Assemblages

Sri Lankans aren’t new to employing bestial metaphorizations for sections of its citizenry. The sword-bearing lion, depicted on its national flag and the state emblem claims to represent the Sinhala people who constitute the majority of the population. The Tamil Tigers, who took up arms against the Sri Lankan state calling for a separate ‘Tamil homeland’, chose the tiger as their totem and the term was used by some supremacists, especially at the height of the civil war, in racist vitriol against Tamils at large. The image of the pig, is often weaponized in islamoracist rhetoric directed at the country’s Muslim minority. In contrast to the privileging of the brave sword-bearing lion, the ‘faggot’ butterflies, like the ‘terrorist’ tigers and the Muslim ‘swine’ are disqualified from the national(ist) imaginary.

Photo credit: Butterflies for Democracy

The initial response by the masses present at the political rally, to this proud invocation of queerphobia by their President, was to timidly chuckle. The awkward chuckle gradually developed into an impressive performance of hauntingly loud laughter. Soon, applause rippled through the crowd, almost as if to prove their ‘heterosexual’ allegiance to the gazing President.

The affect of the moral panic invoked by the President ‘sticks’ fear in the heterosexual(ized) citizenry that the nation is endangered and is under threat because it has come under the rule of a ‘weak’, ‘effeminate’ queer man who has taken what’s rightfully theirs. The queer intruder’s failed masculinity is the reason the economy is in shambles. His effeminacy is the reason unemployment is soaring. His faggotry is the reason there is no food on your table. His sodomy is the reason national security is threatened. The logic narrativized is that queer bodies should be disenfranchised, denationalized, decitizenized and should not be granted the same civic and political rights that the constitution grants ‘all’ Sri Lankans — the right to run for office and if elected, the right to hold public office: because ‘not just any (body) can be a citizen’. Heterosexuality becomes synonymous with loyalty to the nation while queerphobia becomes the technology that legitimises the coup that was under-way.

Being a large public gathering attended by thousands, it’s not unreasonable to assume that there would have been some ‘butterflies’ amongst the crowd present at the rally that evening. How would their bodies respond to being hit by these words? Jayasinghe suggests that the ‘butterflies’ amongst the crowd would have responded by laughing louder and clapping harder as an instinctual survival mechanism so as to not give themselves away. By joining the laughter and applause, they are aligning their bodies with the oppressor’s in an effort to ‘pass’ as one of them. These motions would come unconsciously to their bodies, after a lifetime of obedience to the governmentality and biopower of ‘compulsory heterosexuality’. As such, passing acts as a grotesque tool of adaptation and collusion but also a technology ensuring security of life and livelihood. ‘Passing, like hope, keeps (them) sane’.

As bodies of some of ‘butterflies’ responded by applauding the President’s queerphobic attack as a life technology of survival; other groups of queer Sri Lankans responded to their President by organizing themselves and occupying public spaces with their bodies, carrying signs that said ‘butterfly power’ and ‘Mr. President, butterflies are also voters’. The publicness of this butterfly assemblage refused the domesticity into which the President attempted to dispose of their bodies.

Photo credit: Vikalpa.org, Equal Ground & Butterflies for Democracy

The affect of the same queerphobic pronouncement triggered two distinctly different reactions. As one group of butterflies cringe back into the cocoon by cheering on their President’s attack, other butterflies are spreading their wings unapologetically on the streets of Colombo in ‘pride’. In doing so, as the fabled butterfly does, with the flapping of its wings, they set off a revolution.

In the Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Paulo Freire says, ‘the oppressed suffer from the duality… They discover that without freedom they cannot exist authentically. Yet, although they desire authentic existence, they fear it… Negotiations between these affective dialectics of fear and freedom are stuck to the bodies of ‘butterflies’ from a young age.

Exorcising Colonial Hauntologies

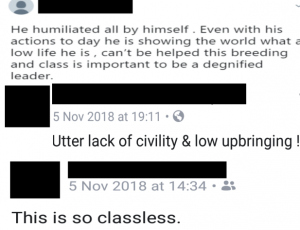

While we examine the affect of the statement made by President it’s also important to problematize the counter affect mobilized by the elite, urban ‘illiberal liberals’ of Sri Lankan society, to the President’s queerphobic performance. In their reactions, a common script was figuring the President as an uninformed villager and a farmer who ‘doesn’t know any better’.

The underlying logic is that the villagers belong on their farms and not in the labour of government which is an elite establishment. Secondly, that queerness can only be understood and performed by those who live in the cities who are exposed to white, Western, secular understandings of sexuality which immature and pious ‘common village folk’ stuck in the village closet know nothing about. This homonormative decoupling of the cosmopolitan queer from the conservative villager, constructs the villager not only as incapable of performing queerness, but also as inherently and perpetually queerphobic.

This city – village, binary represents a (re)production of the neo-colonial homonationalist East – West binary, where the West is constructed as the cradle of civilization and the epitome of sexual liberation in contrast to repressed far-away lands in the ‘East’ from where oppressed women and queers are struggling to escape. In order to trouble these reductive binarizations, between the city and the village, the east, the west and insiders and outsiders, it’s important to situate these debates against the backdrop of colonialism, during which black and brown slave bodies were seen as ‘immoral, perverse and libidinous’.

Historicization also provides genealogies for these sexualized and classed underpinnings of leadership. One example is a letter by a white Portugese soldier who is quoted writing ‘the sin of sodomy is so prevalent (in Sri Lanka)… that it makes us very afraid to live there. If one of the principle men of the kingdom is questioned if they are not ashamed to do such a thing as ugly and dirty, to this they respond that they do everything that they see the king does, because that is the custom among them’. The colonial ‘civilizing project’ not only binarized indigenous understandings and performances of gender and sexuality; it also replaced existing hierarchies of caste and kinship with imported capitalist class structures. Sri Lanka’s post-colonial nation-building project went hand in hand with the rise and institutionalisation of classisms and elitisms.

Jacques Derrida coins the term hauntology to describe a situational disjunction such as a ghost who arrived ‘from the past and appears in the present’. Colonialism has left the ‘former’ colonies in a perpetual state of hauntology. It’s a thing of the past, forever stuck to the minds, words and bodies of the colonized subjects: constantly producing and reproducing insiders and outsiders.

The colonies need to recover from their amnesias of embracing and celebrating colonialist epistemologies as their own. This, however, should not result in a fetishization of a romanticized precolonial past, which was far from a hierarchy-less utopia. It is important to exorcize the ways in which class and sexuality continue to (re)produce each other in the ‘former’ colonies. These otherisms even haunt the language and the very script used in the ‘liberal’ politics and activisms that claim to contest sexual hierarchies.

Saleh-Hanna says that colonial systems of control through which race, class, gender, and sexuality are constructed, conquered and enforced should be exorcized. Exorcism rituals are held in Sri Lanka to ward off demons when a person is believed to have been possessed by one. These rituals, involve performances with dancers dressed as various demons. Offerings are presented to the ‘demon’, in exchange for which the demon agrees to leave the possessed subject.

Perhaps what is needed is a decolonial feminist, queer (or butterfly) ‘exorcism’ to rid the subaltern of the hauntology of colonialism and maybe then, this ghost would ward off from perpetually haunting our bodies.

*The writer would like to thank friends and comrades – Pasan Jayasinghe and Dr. Chamindra Weerawardhana whose writing and resistance (if you could ever separate the two) inspired this piece.

Senel Wanniarachchi is currently pursuing an MSc in Human Rights at the LSE on a Chevening Scholarship. In Sri Lanka, he co-founded a youth movement called Hashtag Generation which mobilizes young people to demand that the country’s political spaces be more inclusive. He also worked at the Advocacy Team of the Family Planning Association of Sri Lanka. In 2018, he co-authored a publication called a Montage of Sexuality in Sri Lanka which was a compilation of stories on the sexual and gender diversity in Sri Lanka. He tweets at @Senel_W.

Senel Wanniarachchi is currently pursuing an MSc in Human Rights at the LSE on a Chevening Scholarship. In Sri Lanka, he co-founded a youth movement called Hashtag Generation which mobilizes young people to demand that the country’s political spaces be more inclusive. He also worked at the Advocacy Team of the Family Planning Association of Sri Lanka. In 2018, he co-authored a publication called a Montage of Sexuality in Sri Lanka which was a compilation of stories on the sexual and gender diversity in Sri Lanka. He tweets at @Senel_W.