by Senel Wanniarachchi

“Your victory

Was so complete

Some among you

Thought to keep

A record of

Our little lives

The clothes we wore

Our spoons, our knives”

—Lenard Cohen, Nevermind

I am at the entrance to the British Museum and the path separates into two. I take the path which appears to be less crowded and a guard interrupts me saying this entrance is for ‘members-only’. I apologize, take the other and stand in a queue for several minutes. I pass through barricades that separate the members from ‘the other’ which leads me to a checkpoint. It’s my turn to have my bag checked and suddenly I’m conscious of my brownness. Soon, I find myself facing the British Museum. The building’s personality is intimidating and reeks of power. As I walk in I am reminded that the history of this building and this city is intrinsically entrenched to my own and that of my ancestors, and I am reminded of my place in the world and its hierarchies. As I walk in, I see a sign that reads ‘The British Museum — collecting the world’.

Photo credit: Sennel Wanniarachchi

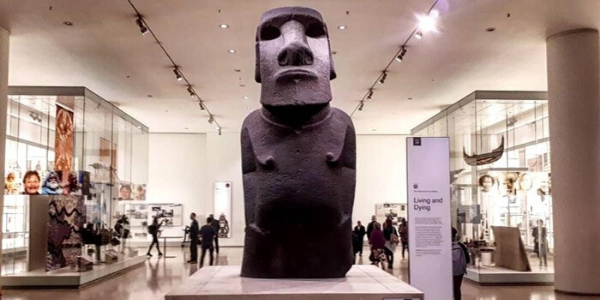

Soon, I am lost amid glorious looted treasures – the Rosetta Stone from Ancient Egypt, Parthenon marbles from ancient Greece and a Moai statue from the Easter Islands. Even the biggest cynic cannot deny that the museum is a grotesquely impressive custodian of memory preserving people’s fears, broken dreams, and fantasies; like a tragic yet magical cemetery. French art theorist André Malraux once noted, that ‘a museum has always been an artificial concept, a wrenching of objects not into context but out of it’. However, there is very much a context to the British Museum — it’s an institutional legacy of colonialism, white supremacy, slavery, and genocide.

Photo credit: Sennel Wanniarachchi

I collect a headphone, the piece of technology that would guide me across the museum. Odd euphemisms are used to refer to how the artifacts were ‘acquired’ —‘governed South Asia’, not ‘colonized’, ‘suppressing unrest’, not ‘mass killing’. Soon, I am drawn to the Museum’s long South Asian Gallery where I see Shiva, the Hindu god of destruction dancing on a circle of fire, Saraswati the goddess of knowledge, and a shadow puppet of Mahatma Gandhi. I feel a strange sense of solidarity with these inanimate artifacts. At the end of the gallery, I find the infamous Tara, standing tall atop a plinth gazing at me. Tara is a Buddhist and Hindu mother goddess of mercy and generous compassion. Her bronze statue plated in gold was stolen from Sri Lanka’s Kandyan Kingdom when the British colonized the island in 1815. Tara’s upper body is completely naked with a sarong draped around her hip concealing her body waist down. Her right hand is in the gesture known as varadamudra – of granting a wish.

Photo credit: Sennel Wanniarachchi

At the museum, almost everyone passing by stops to take a look at Tara. A young white couple stands adjacent to me. The young man whispers something in his female companion’s ear. They both giggle. I’m inclined to assume it was a joke laden with some sexual innuendo. Many aren’t aware of Tara’s genealogy or her divinity. Many wouldn’t care. She fulfills an exoticized oriental fantasy. The audio explains that Tara was ‘given’ to Robert Brownrigg, the third Governor of Ceylon (as the British referred to Sri Lanka). Brownrigg had ‘donated’ it to the museum ‘perhaps finding her voluptuous form rather out of place in his English country home’. However, Tara was considered to be too obscene and perverse to be exhibited to the public. Her exposed bronze breasts too big, her waist too narrow and her hips too curvaceous for the respectability of the white gaze. As such, she was locked up in a discreet storeroom, aptly named ‘the Secretum’ for nearly thirty years. The Museum was mandated to create the Secretum, colloquially known as ‘the porn room’, through the 1857 Obscene Publications Act which gave the state power to destroy material it deemed offensive and obscene.

Photo credit: Sennel Wanniarachchi

Here was a Sri Lankan mother Goddess worshipped by her devotees, stolen and taken by force to a foreign land where she is treated as some pornographic knick-knack only to be locked up in a storeroom along with phallic antiquities and European erotica that display orgies, bestiality and whatever else was deemed too indignant for the holy white gaze. Only adult white male specialists of ‘mature years and sound morals’ who constituted the very apex of the social hierarchy had access to enter the ‘Secretum’ for their pathologizing intellectual gaze. These scholars probably used Tara to enrich their knowledge system of ‘scientific’ racism that drove colonialism — the libidinous, ‘out of control’ non-humans were vice-indulgent and so were their vain gods. For the natives in the ‘Orient’, she represented mercy and compassion. The brown devotees who wanted to escape the illusion and suffering of the endless cycle of birth, death, and rebirth of samsara would stare into her bronze eyes and meditate. This would have perplexed the white missionary slave masters for whom she represented a sinful profanity. How could a naked woman be a God? A God so religiously venerated that even the most powerful of men would kneel before her image, join their palms and pray? They were convinced that these queer emasculated leaders weren’t capable of governing their lands and people and as such, colonialism was not only justified but also inevitable.

For their white gaze, Tara wasn’t any woman, she was pornographic. How could one meditate while watching porn? For the Asians, the sensual and the spiritual were always interconnected and interdependent, perpetually producing and reproducing each other. In Vajrayana or tantric Buddhism, sexual yoga is treated as a form of meditation. However, the British, who failed to comprehend this hypersexualized dichotomy, concurred that the effeminate natives needed the white masters to civilize, not just them, but their Gods. As the missionaries ‘civilized’ the brown Buddhists, they inadvertently ‘civilized’ their Buddhism, and a new kind of rehabilitated Buddhism emerged– a Protestant Buddhism.

The language of conquest was taxonomically allegorized by gender and sexuality. The manly and bold Europe penetrates the effeminate ‘orient’ with exotic landscapes and strange non-humans who worshipped licentious naked Gods.

Attempting to meditate looking into Tara’s bronze eyes, I was reminded of what Sri Lanka would have once been, before the island and its inhabitants were marked by colonialism. For the white colonial masters, the island was full of sin and vice. Like Tara, the brown Asians audaciously exposed their bodies in the tropical sun with only a ‘small bit of cord around the loins from which hung a piece of cloth … covering their natural nakedness’. Polyandry was customary as men had ‘but one wife, but a woman often had two husbands’. ‘The sin of sodomy’ was ‘so prevalent’ and with the absence of binarized performances of gender, the colonial masters often found themselves looking at the brown natives under tropical palm trees in confusion wondering ‘men or women?… these males are so perfectly beautiful that one’s gaze can be fooled’.

The audio in my ear whispers that Tara was perhaps buried in soil for protection from invaders causing the scars across her face and body. The image of Tara’s body traumatized by scars reminds me of how Sri Lanka continues to be marked by colonialism. To please our colonial masters, we learned to regulate ourselves and each other and to be ashamed of our brown bodies and conceal them in shame. The same temples that were home to female deities like Tara, deny women access as they ‘sinfully’ menstruate ‘dirty’ blood. We memorized the masters’ language and started sharing their obsession with hierarchies such as heteronormativity, patriarchy, and capitalism. We now perform their binarized gender roles for them better than the masters themselves. Our militarized nationalisms treated the minorities within our communities the way our slave masters treated us. We appropriated their monogamous marital family as the primary site of surveillance of ‘compulsory heterosexuality’. Our state institutionalized colonialism in all its arms, from the military to politics and education to tame its populations and massify them into these molds, using biopower to regulate every raised eyebrow, every condescending giggle, and every embarrassed look. Our legal infrastructure is a residue of colonialism, not one based on Buddhist or Hindu jurisprudence. Our Obscene Publications Act is much like the one which mandated the creation of the Secretum. Our penal code criminalizes homosexuality and the Vagrants Ordinance criminalizes sex work. These laws were mobilized to punish deviance and most of us abided through ‘self-governance’ in fear of the carceral state. The post-colonial monolithic Sri Lankan state metamorphosed itself to please the masters’ understandings of chastity, virility, domesticity, and respectability and we ‘emulate and simulate’ these ‘moral codes’ as if they are our own culture. A new post-colonial brownness was recreated to be in a perpetual struggle to achieve whiteness both physically & ontologically.

Photo credit: Sennel Wanniarachchi

The audio tells me that the precious gems that decorated Tara’s hair are now missing. Colonization robbed us not only of our gems but our soil, our air, our sexuality, our language, our culture, and our gods. We complied to please our colonial masters and to show to them that we are respectable and are capable of governing ourselves. Today, the same master looks back at us and says we are too illiberal, unenlightened and conservative, our masculinity too toxic, our femininity too servile and our culture and religion too backward, for practicing these very things we appropriated from them. ‘The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house’. When will we admit that this purity is a performance? That we are erotic? That we were the original ‘free the nipple’? That some amongst us are queer? That some of our ancestors were sex workers?

Museums construct certain ‘narratives’ of history, and the British Museum’s narrativization is one of history as written by the victors, of the ‘executioner having the last word’. Representations of colonialism as adventurous expeditions to ‘collect the world’ erase the struggle of the natives and reproduce orientalist fantasies. We need to reclaim these stories, our brownness and our erotic which is our power.

Photo credit: Sennel Wanniarachchi

However, unmoved and unaffected, Tara stands tall as a silent yet deeply political act of resistance and a reminder of a pre-colonial past where a naked woman was a goddess who brought the most powerful of kings, priests and generals in ‘the Orient’ to their knees.

There have been several requests from Sri Lanka calling for the return of Tara and other artefacts. Looking into her eyes, I am unsure if Tara should to be brought back to Sri Lanka. Colonialism has erased something so intrinsic about the island that I am no longer sure if she is even welcome. The audio in my ear concludes voyeuristically, ‘before you move on, admire her from every side’. I look at Tara’s left hand, the varadamudra, and say a prayer for my beautiful country.

Senel Wanniarachchi completed an MSc in Human Rights at the LSE this year on a Chevening Scholarship. In Sri Lanka, he co-founded a youth movement called Hashtag Generation which mobilizes young people to demand that the country’s political spaces be more inclusive. He also worked at the Advocacy Team of the Family Planning Association of Sri Lanka. In 2018, he co-authored a publication called a Montage of Sexuality in Sri Lanka which was a compilation of stories on the sexual and gender diversity in Sri Lanka.

Senel Wanniarachchi completed an MSc in Human Rights at the LSE this year on a Chevening Scholarship. In Sri Lanka, he co-founded a youth movement called Hashtag Generation which mobilizes young people to demand that the country’s political spaces be more inclusive. He also worked at the Advocacy Team of the Family Planning Association of Sri Lanka. In 2018, he co-authored a publication called a Montage of Sexuality in Sri Lanka which was a compilation of stories on the sexual and gender diversity in Sri Lanka.