Notwithstanding criticisms, Conditional Cash Transfer (CCT) schemes as a means of poverty alleviation and social justice in countries with higher levels of socio-economic inequality have seen substantial surge in popularity in the recent decades. While being appreciated as instrumental in making women economically independent precisely as many of them are direct recipients of cash benefits, and in this process, enhancing their sense of self-worth, CCTs have been critiqued for assigning sole responsibility to women for meeting the conditions of such transfers. Importantly, CCTs often fall short of addressing long term and sustainable structural solutions essential to poverty alleviation.

In the contemporary Indian context, successive governments – both at the central and state levels have backed several CCT schemes for various marginalised groups. Within this, socio-economic and cultural advancement of women as a key policy theme has increasingly gained prominence in government agendas. This particularly comes in the wake of women emerging as a distinct electoral constituency; reflected both in the higher number of women voters in recent elections as well as in the qualitative shift in favour of the deepening of women’s voting autonomy. While policies targeted at women’s development generally claim adherence to progressive social discourse, they are also grounded in cultural contexts of gender inequality and societal conservatism. Of this, the complex gender norms that structure government policy in the east Indian state of West Bengal where All India Trinamool Congress (AITC) led government, headed by Mamata Banerjee, which has backed several CCT schemes is a case in point. Banerjee’s style of personalised leadership is reflected in the conception, naming, implementation and propagation of the CCT schemes. The extensive popularity of these schemes has served to augment the AITC’s electoral support base in West Bengal, particularly among substantial sections of women voters. In this post, I explore what can be identified as a fundamental disjuncture between the stated aims of two of these schemes – Kanyashree and Rupashree, both of which target girl students from low-income groups as their direct beneficiaries. Thinking through the politics of gender that frames discourses of state policy is part of my larger doctoral project on the gendered institutional cultures of party politics in West Bengal.

Among the different CCT schemes under Banerjee’s administration, the intensive state-driven media advertising of Kanyashree through songs and other audio-visual means has effectively established it as the flagship scheme, with August 14 being declared as ‘Kanyashree Day’. The paradigm of social welfarism within which Kanyashree is situated also comprises other CCT schemes targeted at diverse social constituencies. Examples include financial support for housing among low and middle-income families, food security for citizens living below the poverty line, bicycles for young students, cash transfers for the disabled, and cash benefits for cremation/burial purposes. Even as it operates within the same ambit of policymaking as Kanyashree, the relatively recent Rupashree scheme is distinguished by its particular vision of women’s socio-economic enhancement, with policy implications contradictory to those of Kanyashree. In what follows, I explore the contending visions of the two schemes while evaluating their policy implications within the larger socio-cultural constructions of gender.

Initiated in 2013, Kanyashree aims to encourage more girl students between the age of 13 and 18 to continue with higher education while aiming to curb school drop-outs and child marriage. At present, the scheme records over 6 million beneficiaries. It stood first in UNESCO Public Service Awards in 2017 among 552 project nominations from 62 countries. The scheme includes annual cash benefits of 1000 INR till the applicant reaches the age of 18 followed by a one-time financial grant of 25,000 INR if the applicant continues her studies without getting married. In contrast, Rupashree, a marriage assistance scheme modelled after a similar programme launched in the state of Tamil Nadu, targets low-income families intending to arrange their daughters’ marriages with the condition that at the time of application, the prospective bride and groom must be at least 18 and 21 years of age respectively. Launched in January 2018 as part of the State Budget, the scheme offers a one-time financial grant of 25,000 INR to what it designates as ‘economically stressed families’ during the time of their daughters’ weddings. The stated aim of this scheme being the alleviation of wedding expenses for ‘poor’ families, it is premised on rather traditional as well as problematic representation of unmarried young women as a ‘burden’ on their families. Notably, this is in sharp contradiction to the vision of the Kanyashree project that aims to facilitate higher education prospects for young women in West Bengal while deterring child marriage and associated risks of early pregnancy, maternal and child mortality. Offering low-income girl-students aged 18 years the prospect of higher education (Kanyashree) on the one hand, and marriage (Rupashree) on the other, Banerjee’s policy framework has been critiqued for weakening the goal of women’s economic autonomy. The potential implications that a policy like Rupashree holds for reinforcing the practice of dowry is noted in a study on the implementation of a similar scheme in Tamil Nadu. As the study shows, a substantial section of recipients tend to spend cash benefits on purchasing two-wheeler vehicles as dowry for marriage. These divergences between the two projects assume more clarity upon undertaking a comparative analysis of their guidelines.

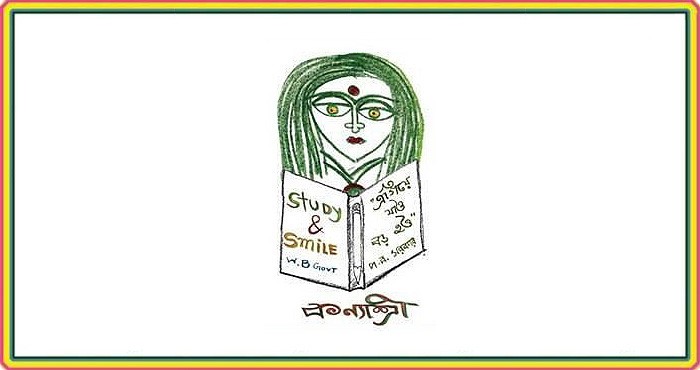

Issued by the Department of Women and Child Development and Social Welfare, the Kanyashree guideline and the Rupashree guideline are policy documents outlining the provisions, eligibility criteria, implementation, monitoring and grievance redress mechanisms. It is thorough discussions on the rationale for CCTs and gendered implications of child labour, trafficking, and child marriage and their monitoring apparatuses that render the Kanyashree guideline more comprehensive than Rupashree. While the Kanyashree guideline embodies prevalent socio-economic discourse of development – as demonstrated by its frequent use of concepts like ‘feminisation of poverty’, the rather concise Rupashree guideline is marked by its technocratic tenor and terseness of prose to describe the policy and implementation designs, which has been undertaken without establishing a rationale for the scheme. In addition, whereas individual girl students constitute the direct recipients of cash benefits in both the schemes, the Rupashree guideline effectively identifies low-income families as the beneficiary units. This emphasis on families as units counters the Kanyashree guideline’s avowed objective of enabling individual girl students to forge ‘a sense of self, personal capacity and well-being’. The difference in their gendered approach is further underlined by their emblems:

Image A: The Kanyashree emblem

Image B: The Rupashree emblem

In image A, the Kanyashree logo features a young woman with a book. Its cover reads, ‘Study and Smile’ on one part and ‘Egiye Jaao’ (Move Forward) on the other. The woman has a steady, brooding and determined gaze pointed at the book and is adorned by a medal around her neck. Image B is of the Rupashree logo featuring a woman decked in Hindu bridal attire with a demure and downcast gaze.

Within the AITC, the success and international acclaim of Kanyashree has entirely been credited to party supremo Banerjee, reifying her image as ‘liberator’ of marginalised social groups including women. This was reflected in an interview I conducted with a woman AITC worker where she drew links between socio-cultural deprivations faced by aspiring low-income girl students and Banerjee’s empathic capacity to devise ‘ingenuous’ solutions. In contrast, women political workers of the left-wing Communist Party of India (Marxist) as well as the right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party raised a range of objections to the CCT schemes. These included characterising the schemes as ‘giveaway of leftovers’ and ‘Khairati’ (charitable donations) to personally accusing Banerjee of ‘repackaging’ central government-sponsored schemes as those of the state government.

While the divergent and conflicting objectives of Kanyashree and Rupashree signal a fundamental incoherence at the level of policy-making, they also illustrate the government’s attempts at simultaneously catering to the sentiments of its progressive and conservative constituencies and support bases. Despite this disjuncture, a closer look at the naming of these schemes offers notable insights into the discursive commonality undergirding these frameworks. Both Kanyashree and Rupashree connote aestheticised Bengali adjectives for young women. Kanyashree denotes the charm of a young girl while Rupashree lays emphasis on her physical beauty. The Rupashree scheme highlights the channels through which socially conservative gender norms are reaffirmed even as its award-winning counterpart- Kanyashree, facilitates the challenging of those very norms. At the same time, traditionalist cultural representations of women as repositories of physical beauty and grace inform both frameworks. In conclusion, illustrating the subterranean congruity between the two otherwise contradictory schemes helps understand the ways in which hegemonic gender constructions weave into the practice of developmental policymaking, with resultant policies often mirroring socio-cultural conventions they claim to subvert.

Proma Ray Chaudhury is a PhD Candidate at the School of Law and Government in Dublin City University under the EU Marie Curie ETN Global India Project. Her thesis, titled ‘Gender and Political Parties in India: Pathways to Women’s Political Participation?’ studies the role of political parties as avenues for political mobilisation, participation and representation of women. It analyses the political parties of the state of West Bengal in India in terms of their institutional party cultures and explores the obstacles and opportunities that these shifting cultures present for women’s active political participation. This project is funded by a Horizon 2020-funded European Training Network, Global India (grant number 722446).

Proma Ray Chaudhury is a PhD Candidate at the School of Law and Government in Dublin City University under the EU Marie Curie ETN Global India Project. Her thesis, titled ‘Gender and Political Parties in India: Pathways to Women’s Political Participation?’ studies the role of political parties as avenues for political mobilisation, participation and representation of women. It analyses the political parties of the state of West Bengal in India in terms of their institutional party cultures and explores the obstacles and opportunities that these shifting cultures present for women’s active political participation. This project is funded by a Horizon 2020-funded European Training Network, Global India (grant number 722446).