By Rosa dos Ventos Lopes Heimer, Marcela Terán and Tatiana Garavito

*Illustrations by Marcela Terán

In early 2020 as the pandemic broke out, we witnessed first hand the various ways in which our own lives and those of our communities have been deeply affected. As Latin American migrants living in London already separated from our families of origin, we were suddenly also cut off from our second families here while overtaken by fear, hopelessness, and guilt as we were told that the best way to care and be safe was to ‘stay at home’. These feelings were soon augmented by rage, anger, and frustration towards a system that continued to put profit over people.

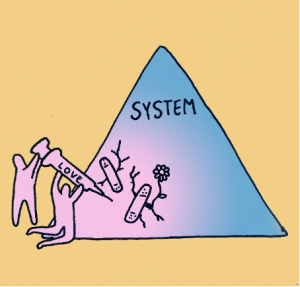

The pandemic generated a specific kind of affective atmosphere amongst some of us Latin American migrants collectively calling us into action. Feeling powerless and isolated whilst also being hyper aware of the privileges some of us hold, we decided to promptly re-awaken and repurpose our networks and skills built on years of grassroots activism to create a collective care migrant initiative run by and for Latin Americans. As activists, we are used to coming together to build community, imagine and design new ways of moving forward, meeting our collective needs and confronting violent structures. And since many of us had previously collaborated together, there was a strong foundation built on trust. Rooted in an ethics of love, care, and solidarity, in the spring of 2020, we set up Apoyo Comunitario, a London-based migrant-led feminist collective.

In many ways, this initiative became a community-based affective response to channel our emotions and to, at least partially, address collective survival needs left unmet by violent state inaction. Migrants, in particular, racialised undocumented migrants, those with no recourse to public funds, who are women, survivors of violence, queer and/or disabled are exposed and need to survive the state necropolitics. That is, a state-sponsored politics which creates and exacerbates vulnerability to premature death. Whilst this has been a long persisting reality in the UK, the context of COVID-19 has significantly worsened this. Faced with a system that does not care for migrants and which most of us are not really meant to survive, meant that we had to be inventive and resourceful, turning to community care as a survival strategy, as “political warfare”, to quote Audre Lorde. That in itself is a radical act, as Sara Ahmed suggests, because “sometimes: to survive in a system is to survive a system”.

Our decolonial feminist care praxis has tried to be attentive to the interdependent relationship between the personal and the collective, as they both connect and relate to the political. We politicise and contextualise the self and the collective, recognising ourselves as a community yet one that recognises individual differences which translate into varying caring needs that must be listened to and accounted for. As bell hooks reminds us, in a society that praises individual success, cultivating an ethics and practice of care is counter cultural. Similarly, in a society that is built on oppression, cultivating an ethics and practice of love, especially towards and among those who are not meant to survive, can become counter hegemonic.

We were fully aware that a lot of Latin Americans do not speak English and therefore would not be able to reach existing and emerging community care infrastructures. Therefore, we attempted to work as bridge with our initial work involving translation, interpretion and signposting to enable Latin American migrants to access support from mutual aid groups, food banks, workers’ and renters’ unions, health services, NGOs, and so on. Through this we quickly became aware of an acute gap in existing provisions, and how migrants with insecure and undocumented status who were being laid off due to the crises, in particular those with ‘no recourse to public funds’ were falling — or rather being pushed — through the cracks. Neither able to access government furlough schemes nor the (insufficient) sums provided through Universal Credit, many were in dire financial positions unable to heat, keep their houses or cover essential expenses.

Listening to this need, we launched an online crowdfunding page and applied for various grants in order to set up a small COVID-19 Hardship Fund for migrants with no recourse to public funds, through which we initially provided weekly financial support to as many people as the funds allowed. This work has been informed by a reparative justice lens, redistributing small but meaningful amounts of money to communities systematically disadvantaged, from whom resources have historically been extracted. We also wanted to ensure the way we administered the Fund was informed by our ethics of love, care, and solidarity, treating recipients of the fund with respect and dignity. In practical terms this means collaborating horizontally, trusting one another, and moving together. Through telephone calls with those applying for the fund, we encourage them to assess their own situation and need, taking their word for it. We also do regular check-in calls to help nurture these relationships and to enable them to tell us if their situation changes, so they can play an active role in making funds available to someone else in need. We are also continuously revising our approach based on these conversations and emerging needs.

In this process, we tried to listen to and recognise the ongoing collective traumatic experiences of migrant communities that lead to distrusting authorities, policing practices and being fearful of sharing personal data – which are legacies of a criminalisation logic put forward by the hostile environment. This meant setting up a secure system to manage people’s personal data and being mindful of how much information we ask them to provide. We also had to push back against funders and institutions who wanted to impose their rules, objectives, and ways of working. In this case, solidarity has meant taking a reparative approach to educating organisations with power and resources, encouraging them to take responsibility for the harms they have historically created and power dynamics within philanthropy so that the approach is centred around dignity and respect rather than power and control. In practice that meant having long conversations, refusing to collect and provide some types of data, suggesting more flexible and qualitative approaches to reporting on funding and collaborating with more established organisations that met specific funders’ requirements but would not ask us to compromise our values and praxis. We have also followed a ‘solidarity, kinship and not charity’ principle that has manifested itself in our work in the way we care for each other, build relationships of trust and mutual respect through listening and advocating for each other.

Over the past year we have redistributed almost £30K supporting over 60 individuals and families. When the first lockdown ended, pressure on the fund receded a little, but we continued to support a number of families. Once two grant applications were successful and the Crowdfunder stopped generating so much income, we engaged in a consultation with people we had supported. We then moved to a new system of deeper support for a small number of people whose situation is particularly acute, complemented with a one-off Emergency Fund for people who continue to request support.

Our decolonial feminist care praxis is rooted in relationality, therefore, as Fiona Robinson contends, it is not “about assisting, protecting or ‘saving’ others who are less fortunate or ‘less developed’; rather, it is about developing the capacity to listen to others and to learn from their ways of being in the world”. Our care ethics is defined and re-worked through praxis. Listening is integral to this praxis; it is imperative to ensure that our ways of caring are in line with our respect and fight for self-determination. Listening is key to establishing solidarity in terms that are meaningful to those who are being cared for instead of simply defined by our own revolutionary desires. This intimately connects with the Zapatista principle of mandar obeciendo or “leadership from below”. As we aim to be horizontal, we ensure we listen to our communities and are led by those who, given structural inequalities and uneven distribution of resources, are often unable to actively participate in the core organising group.

Our decolonial feminist care praxis is rooted in relationality, therefore, as Fiona Robinson contends, it is not “about assisting, protecting or ‘saving’ others who are less fortunate or ‘less developed’; rather, it is about developing the capacity to listen to others and to learn from their ways of being in the world”. Our care ethics is defined and re-worked through praxis. Listening is integral to this praxis; it is imperative to ensure that our ways of caring are in line with our respect and fight for self-determination. Listening is key to establishing solidarity in terms that are meaningful to those who are being cared for instead of simply defined by our own revolutionary desires. This intimately connects with the Zapatista principle of mandar obeciendo or “leadership from below”. As we aim to be horizontal, we ensure we listen to our communities and are led by those who, given structural inequalities and uneven distribution of resources, are often unable to actively participate in the core organising group.

We understand care as a community practice of survival, horizontality and reciprocity, so even though members of our core group may be in more privileged positions to do the work of caring, care is directed to all. This is especially considering that activist patterns of caring for others in detriment of one’s own wellbeing have often led to burning out, in particular among Black and women of colour communities, something that many of us have experienced and/or witnessed first-hand in the past in our own organising circles. From the start, it thus became imperative but also intuitive to create an internal group culture of care as well as embedding it into our practices and processes. Practically, this was done through organising group care sessions; being honest and transparent about our emotional and practical capacities; being mindful of how work was distributed; and if necessary, redistributing the labour or slowing down. In doing so, we have enacted a decolonial feminist care praxis that aims at challenging the Western dichotomy between those who care and those who are cared for whilst moving away from saviour narratives.

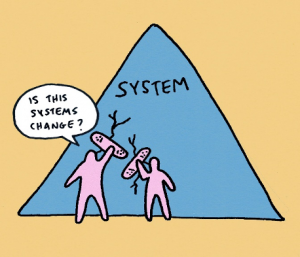

Even though we have started a campaign and have been excited to collaborate with other groups in political education initiatives, listening to the priorities set by our community and our own capacity constraints meant that we often needed to limit our engagement and divert our resources. Having to do so, at times, troubled us, for we feared we were diverting from doing the ‘radical’ work of system change. However, if we, as bell hooks argues, acknowledge “the interlocking, interdependent nature of systems of domination”, recognising that domination necessitates violence to sustain itself, then focusing our efforts on nurturing love and community through service is not a distraction from tackling root causes, but possibly one of the most powerful things we can do—not only to survive the current system, but also to dismantle its core. As hooks teaches us, a love-ethic, “emphasizes the importance of service to others… Service strengthens our capacity to know compassion and deepens our insight. To serve another I cannot see them as an object, I must see their subjecthood.”

Even though we have started a campaign and have been excited to collaborate with other groups in political education initiatives, listening to the priorities set by our community and our own capacity constraints meant that we often needed to limit our engagement and divert our resources. Having to do so, at times, troubled us, for we feared we were diverting from doing the ‘radical’ work of system change. However, if we, as bell hooks argues, acknowledge “the interlocking, interdependent nature of systems of domination”, recognising that domination necessitates violence to sustain itself, then focusing our efforts on nurturing love and community through service is not a distraction from tackling root causes, but possibly one of the most powerful things we can do—not only to survive the current system, but also to dismantle its core. As hooks teaches us, a love-ethic, “emphasizes the importance of service to others… Service strengthens our capacity to know compassion and deepens our insight. To serve another I cannot see them as an object, I must see their subjecthood.”

After nearly two years since the start of the pandemic and the coming together of Apoyo Comunitario, our collective is now slowing down its activities and concluding our last project which consisted of funding and supporting small business initiatives led by migrants with insecure or undocumented status. We still have a small emergency fund left which we are distributing among migrants in need. The pandemic has lasted for much longer than expected and it is far from over, and although many of our community needs continue to be left unmet, much has changed since then. Our group has transformed itself, repurposed our approach and learned greatly during this journey. Even though we will soon be concluding our activities, the learnings from our decolonial feminist care praxis will continue to inform other projects our members may be turning to in pursuit of our collective struggle for liberation.

Apoyo Comunitario Sur de Londres was set up in 2020 responding to the disproportionate impact of the COVID-19 crisis on migrant communities, particularly those impacted by the racist No Recourse to Public Funds (NRPF) policy and those who are undocumented. We are a migrant-led feminist collective of Latinxs based in London. Rooted in the principles of solidarity and collective care our work covers three main areas: COVID-19 Hardship Fund; Translation/interpreting; Signposting; and Campaigning. The founders/instigators are Latin Americans, many have a long history of community organising and/or have worked for local Latin American NGOs. We bring together a variety of experiences, skills and sensibilities which have supported us in responding rapidly and meaningfully, in thoughtful and caring ways, to the needs of our community. Three members of Apoyo Comunitario have co-written this piece with input from several other members: Rosa dos Ventos Heimer (PhD candidate and organiser), Tatiana Garavito (facilitator and organiser) and Marcela Teran (designer/illustrator and organiser).

Twitter handles: @Rosaheimer; @IamQuestioning; @TatGaravito