On Wednesday 22nd February 2017, PhD students at the Gender Institute organised a roundtable discussion and interactive workshop titled Practicing Decoloniality in Gender Studies. This short series of posts presents the transcripts of the three speakers’ discussion papers, following up with Louisa Acciari’s call to action in solidarity for outsourced cleaners in UK academic institutions and Brazilian domestic workers alike.

My participation in this event is deeply contradictory; and like my colleagues, I felt it was at the same time necessary and problematic. I am on the panel because I am Brazilian and work on Brazil, yet I am white, grew up in Europe, went through the French and then British education system, and I am currently doing my PhD at the LSE.

In fact, the very reason I am a white Brazilian is because my Italian ancestors were brought to Rio in the 1920s to “whiten” the population. At the time, the Brazilian government was subsidising white European migration as it was believed that a whiter population would lead to a better economic development. My parents did the reverse journey in the 1980s, left Brazil and migrated to France in the hope for a better life. There, they were never privileged in terms of class; they had no degree, did not speak French at the time, had a precarious citizenship status. They worked as cleaners and all the low-paid jobs they could find. But still, we were and remain white, and our class condition was mostly linked to migration. The poverty threshold in France is below 700 euros of income per month, which is already 3 or 4 times the Brazilian minimum wage.

This position is something I have to carry with me when I do my PhD and when I am on fieldwork. I first thought that the best strategy to access and interview domestic workers would be “undoing privilege”, trying to use the fact that I am Brazilian and to be as local as possible. But I cannot undo whiteness, and my appearance creates expectations and assumptions. Most interviewees would first think I was an employer, or a lawyer, and then imagined a very extravagant life for me where I would own a car, have a maid, live in nice posh areas… some even asked me if I had ever met the Queen! My material conditions do not quite correspond to their imaginary, but still, receiving £16,000 a year to do a PhD at the LSE is completely different from earning a minimum wage in Brazil and working as a cleaner or nanny.

Most importantly, my participants liked the fact that I came from Europe, and did not want me to be Brazilian. As soon as they learned about my Europeanness, they would call their friends, take pictures, and would only refer to me as the French, the English or even the American student (at this point, my status had reached its highest level!). For them, there is some prestige in having someone coming from Europe to talk to them, listen to their stories, and bring it back to Europe. They felt honoured and valued.

Now, this is of course very problematic. Because of colonial and imperial legacies, Europe is more glamorous and prestigious than their own country, and they value more the presence of a European scholar than a local one. But the question is, what can I, as a PhD student from the LSE, do about it? And how can I use this situation in the most ethical way possible? I alone cannot undo coloniality, I cannot become less white, erase my life in France or the fact that I am studying at the LSE. But I can try to live up to their expectations, I can indeed bring their stories back here, write them, publish them, and talk about them. I can also use my privileged position to take action.

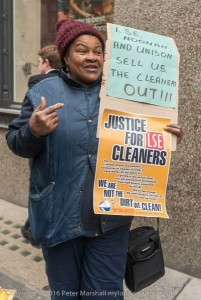

And just when I came back from the field in October 2016, as I was thinking of a way I could organise a workshop in Brazil, or a project to support the unions locally and give something back to them, I was made aware of the cleaners’ movement at the LSE. The cleaners are all migrant workers, all black or minority ethnic, they earn less than £10 an hour, and work under very hard conditions. They are not directly employed by the LSE, but I’ll leave the discussion on subcontracting for another time. A lot of them are women. A lot of them had a different job back home, some Latinos have a degree but because they do not speak English they cannot use it here. And so here I was, in my nice PhD office at the LSE, writing about intersectionality and domestic workers in Brazil, while these migrant cleaners were protesting against their harsh working conditions at the LSE, and campaigning for equal rights just under my nose. I had to do something. I attended some union meetings, went to their events, and started getting involved in the campaign.

One thing that really surprised me, is the similarity between their stories and my participants’ stories in Brazil. I guess I was surprised because I never expected working conditions in the UK, and even less so at the LSE, to resemble that much those of the poorest workers in Brazil. But they are subjected to the same types of harassment, disciplining, mistreatments and prejudice. Cleaning is not a dignified job, not in Brazil, not in the UK, not anywhere. And in fact, many friends told me: “you didn’t have to go that far to study what you’re studying”.

I also kept feeling uncomfortable because I cannot reconcile the fact that we, feminist and critical thinkers, are sitting here, enjoying very good material conditions to do our work, while the cleaners are being undermined and devalued. We are directly complicit with this situation. Black and migrant people are literally cleaning after us so that we can read, think and write. And they are under a lot of pressure for doing it quickly, efficiently, and silently.

But here again, my privileged position means I can do something, and this particular campaign is one way for me to put in practice my theory. As an LSE student, I can say out loud what I think, and stand in solidarity with the cleaners, without facing any of the consequences they will face if they go on strike. I won’t lose my wage; I won’t get fired. I can write about it, I can take part in their protests, give money to their strike fund, organise solidarity actions with and for them. These are all very easy things that I can do because I am a PhD student and not a cleaner.

To conclude, I would like to emphasise one very important thing: recognising our privilege is a necessary step, but it is not enough. What matters is what we do with it, and how we try to use it to have an ethical practice that speaks back to our theory. For me personally, it seems impossible to think and write about intersectionality and subalternity while black migrant sub-contracted and exploited workers are cleaning after me; I need to take action. My involvement in the campaign won’t make my privilege go away, and it won’t solve 500 years of coloniality and imperialism. But it might help improving cleaners’ working conditions and revalue their labour, which is ultimately what I also call for in my PhD, and what domestic workers are asking for in Brazil.

![ProfilePicGI[1]](https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/gender/files/2015/09/ProfilePicGI1.png)