by Swati Narayan

Babloo is too short for his age. In India, and especially in the poor eastern state of Bihar, that is unfortunately not unusual. Two of every five pre-school children are stunted. But Babloo’s malnutrition is so severe that he can barely move and lies on his back all day. With three other children in tow, his mother, herself thin as a reed, is at her wits end.

Even at the start of their pregnancy, 42 percent of Indian women are underweight and as per latest statistics 50 percent are also anemic. So it is perhaps no surprise that half the stunted children in India are born underweight. Underfed mothers are also often not able to breastfeed their infants. This inter-generational transmission of undernutrition stymies generation after generation.

An underage mother breastfeeding her child in Bihar’s Muzzafarpur district | November 2016

So, Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s New Year’s Eve grand announcement to provide a cash grant to pregnant women was welcomed with much fanfare. But disappointingly it turned out to be nothing more than repackaged old wine in a new bottle. In fact for three years the government had scuttled its legal responsibility spelt out in the ambitious 2013 Food Law to pay Indian mothers a modest rupees 6000 ($90) as maternity entitlements for each child born.

Frustratingly, the Finance Minister in his latest budget has further short-changed Indian mothers. With the stingy allocation, not even a quarter of the 27 million pregnant and lactating women in India can be meaningfully covered. Succeeding generations of Indian children will pay the price for this short sightedness.

The Ministry of Women and Child Development is nowlikely to impose conditionalities for eligibility. The cash may be only for first-borns, though subsequent deliveries are usually more vulnerable. Further, 38 percent of children who are not fully immunized may be deemed ineligible. Also 21 percent of Indian children born at home are likely to be disqualified. These conditionalities violate the letter and spirit of universality enshrined in the law. Mothers with the greatest need are also more likely to be left out.

A teacher in her uniform at a government nursery for children under 6 years in Tamil Nadu | July 2010

On the other hand, the progressive southern state of Tamil Nadu already pays mothers twice the amount of maternity entitlements (Rs 12,000 or $180) from its own coffers. Research shows that most women use this money judiciously for nutritious food and medicines, rather than fritter it away. It also helps mothers to rest after childbirth, take time off work, eat better and breastfeed their children for longer durations.

Tamil Nadu also recently began to give new mothers a handy Amma Baby Care Kit. Finland is the inspiration, which for 75 years has been giving all new mothers a newborn “starter kit” with a cardboard crib, childcare products, toiletries and clothes to achieve the lowest rates of infant mortality in the world.

Mothers across the rest of India however struggle to juggle their childcare responsibilities as 90 percent of Indian women work in the informal sector or in unpaid work without any childcare provisions. The Oscar-nominated film “The Lion” movingly portrays the extent of their angst. So almost half of all children are not exclusively breastfed for six months as recommended by the World Health Organisation.

Last week, the Indian Parliament passed the new 2016 Maternity Benefit Bill to provide 26 weeks of paid leave to the 10 percent of women in the formal sector.

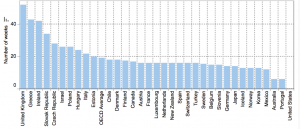

But unlike these privileged few or those developed world, women in the informal sector are unable to accrue generous paid leave. In fact even India’s modest maternity entitlements are barely equivalent to five weeks of minimum wages in Bihar. In contrast, women in Britain receive 52 weeks job-protected leave (of which 39 are paid) and Mexico 12 weeks.

Number of weeks of maternity leave

Source: OECD 2015

Indian women also have a greater burden of household responsibilities while men often barely chip in. Everyday women in India spend an average of five hours on childcare and domestic chores, compared to only 52 minutes for men. This is not only amongst the highest workload but also the most unequal in the world.

Worse, the silent practice of “maternal buffering” – which is the practice of eating less to feed the family more (especially husbands and sons) — is common. The sway of patriarchy is so acute that women also invariably eat last and often the least.

For three years, the government blithely subverted the law. So this year, Right to Food Campaign activists from across India sent postcards to the prime minister to remind him of every mother’s right to maternity entitlements as per the Food Act. In September 2015, even the Supreme Court issued notices to the government for non-implementation. Then last November as another reminder women’s activists from across the country organized a day of action. Signatures and palmprints were collected in various states and sent to policy makers. Press conferences and marches were also organized to drum up solidarity. In labour chowks (squares) and village corners, women expressed their acute need for money, especially in the wake of demonetization, but were largely unaware of their maternity rights.

Women in Jharkhand’s labour square adding their signatures to demand the payment of maternity entitlements | November 2016

Photo credit: Ananya Saha, Right to Food Campaign Jharkhand

Maternity entitlements in India are conceptualized not only as a right for all women, but especially as wage compensation for the 90 percent who toil in the unorganised sector. So Indian activists are demanding universal, unconditional maternity entitlements. These modest sums can go a long way to support and drive home the message – literally – of the greater nutritional and health needs of pregnant and lactating women. Even without retrospective effect from 2013, at least rupees 14,000 crores ($2 billion or a mere 0.1 percent of GDP) are essential.

Babloo’s future and that of millions of India’s malnourished mothers and children — in this generation and successive ones — depends on this small change.

Swati Narayan is a visiting research scholar at the London School of Economics and Political Science’s Gender Institute from the Tata Institute of Social Sciences. She is on Twitter @SNavatar

Swati Narayan is a visiting research scholar at the London School of Economics and Political Science’s Gender Institute from the Tata Institute of Social Sciences. She is on Twitter @SNavatar

*This article is edited and re-published here with permission from its original version in she-files.com. It was re-posted in LSE South Asia blog and Huffington Post.