by Francesca Romana Ammaturo and Koen Slootmaeckers

Every year, around the International Day Against Homo, Bi, and Transphobia, ILGA Europe, the biggest LGBTQI+ umbrella organisation in Europe working on LGBTQI+ rights, releases its Rainbow Index and Rainbow Map into the world. This moment generates a lot of media attention to the plight of LGBTQI+ rights in Europe and provides an important moment in the work of ILGA-Europe. Whilst we recognise the usefulness of this resource in advocacy work, we also see several issues with the mapping of LGBTQI+ rights in this way. In this long read, we explain how maps do not only depict a world, but also generate political narratives that do not always reflect reality. We will particularly demonstrate how the focus on LGBTQI+ rights from its legal perspective can lead to a misunderstanding and sometimes even misrepresentation of actual LGBTQI+ lived experiences. We present our argument in two parts. First, we consider how the use of maps create a new world-view, not always related to lived experiences, with its own political consequences. Second, we empirically analyse the disconnect between the rainbow map and lived experiences to highlight how an uncritical reading of the map leads to the projection of fictional queer utopias and dystopias in Europe.

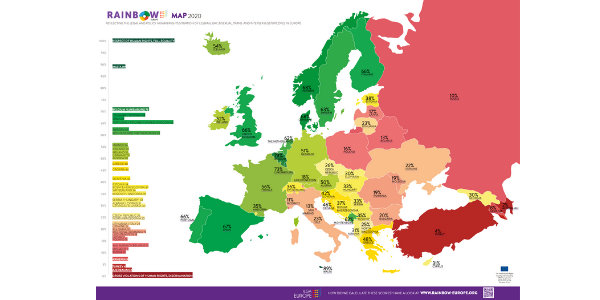

Image credit: ILGA Europe

How the Rainbow map creates and projects a coloured image of the world

While maps help us orientate through the complexities of the physical (and symbolic) world, they are never neutral. Rather, maps act as productive devices that shape and channel our understanding of the relationship between space, politics, and identity. Throughout history maps have been crucial tools in serving the interests of nationalist projects, war propaganda, as well as colonialism and imperialism. Today the role of maps has expanded, and we see them being increasingly used by NGOs as a way to showcase human rights protections and violations. Within this context, (quantified) indicators and their map equivalences are normally deployed as advocacy tools that help initiate conversations on human rights violations at both the national and international level. Whilst certainly useful, Salle Engle Merry reminds us that the indicators underpinning these maps are not technical and or free of politics; they do not simply reveal the truth but rather create it. As such, the growing use of maps in human rights work is not deprived of controversies and ambiguities, particularly when it comes to the widespread advocacy strategy of ‘naming and shaming’ governments that are not compliant with human rights standards. Although we do not intend to critique the NGOs that create these maps, one must reflect on the world these maps create and project as well as the political narratives they shape and how these relate to lived realities.

This year’s publication marks the eleventh edition of the ‘Rainbow Map’, and the way in which ILGA Europe measures ‘progress’ appears to have changed over the years. Whilst in the first two editions of the map (2009 and 2010), icons were used to symbolise which provisions existed in the different national legislations (i.e. same-sex marriage, anti-discrimination legislation, etc.), from 2012 onwards ILGA-Europe started measuring progress using a numerical scale, combined with the adoption of a traffic-light coding system with countries with better human rights compliance in green, those in intermediate positions in yellow, and those with worse compliance in red.

Whereas the traffic-light coding has become an integral feature of the map, the methodology of the index has changed from 2012. Overtime, more and more indicators and criteria of equality have been integrated, virtually moving the bar of equality year by year. At a glance, the use of traffic light colouring – with red signifying non-compliance or danger – contributes to create the illusion of a compartmentalised, as well as dichotomic understanding of countries with ‘good’ track records on LGBTQI+ rights on the one hand, and countries with ‘bad’ records on the other. From a semiotic perspective, traffic light coding can be understood as being signals, that is to say signs that ‘trigger […] some reaction on the part of the receiver’. In this case, the ‘reaction’ could be intended as either the ‘mobilisation of shame’ towards non-compliant governments, or indignation on the part of the civil society. Indeed, once published, the rainbow maps start leading a life of their own, beyond the imagined goals of ILGA-Europe and start influencing queer politics in Europe in a variety of ways. Amongst other things, they generate homonationalist discourses that project ‘queer utopias’ and ‘queer dystopias’ onto the map of Europe. As these projections are solely based on legal contexts, they have severe implication for how we conceptualise, envision and imagine queer lived realities.

As discussed somewhere else, homonationalist discourses also change how we consider the problem of persistent homophobia. Whilst in ‘green’ countries homophobia becomes a problem of not-yet-adjusted individuals, in ‘red’ countries homophobic experiences are a sign of backward not-yet-modernised cultures. Such thinking also displaces the lived experience of queer people. When those living in so-called LGBTQI+ friendly countries experience violence, their experience are interpreted as random instances and systemic structures of oppression are ignored, whilst at the other end of the spectrum queer people are imagined as eternal victims, and positive stories and individual/collective tools of resistance and abilities to create safe space are rendered impossible.

Talking about the use of a similar map produced at the global level by ILGA World to measure levels of homophobia globally, Rahul Rao reminds us that these maps are effectively constituted as ‘(…) ranking exercises [that] mobilise shame, not on the basis of the substantive values at stake in these disputes, but through a reiteration of familiar divides between shamers and shamed’. In turn, this sharp distinction between shamers and shamed can be used to mobilise homonationalist discourses in various national contexts, embodied in a form of ‘rainbow exceptionalism’ consisting in measuring one’s own performance in protecting LGBTQI+ rights vis-à-vis the ‘failures’ of other European states. Ultimately, the unfolding of this ‘rainbow exceptionalism’ creates fertile ground for an even sharper distinction between ‘LGBTQI+ friendly countries’ and ‘non-LGBTQI+ friendly countries’ within Europe, and well beyond its confines (for more on how this plays out in Europe, see our previous work on this here and here).

Hence, within the logics of international LGBTQI+ politics, the production of these maps reproduces hierarchies often mediated by Eurocentric understandings of linear progress, while discounting the crucial importance that an interpenetration of legal and social aspects has in evaluating national contexts in which LGBTQI+ persons live. Therefore, while ILGA Europe’s ‘Rainbow Maps’ have been accompanied since 2011 by an Annual Review that also acknowledges the social context within which the legislative framework is situated within each country, the snapshot provided by the maps themselves does not fully capture the complexity of this interconnection between the legal and how LGBTQI+ people experience inequalities in their daily lives.

Furthermore, the heightened emphasis on the legislative framework of protection of LGBTQI+ rights in each country conveyed by the ‘Rainbow Maps’, we would argue, partly displaces lived experiences of LGBTQI+ people in Europe. As we demonstrate below, for some low ranking countries, the map in part perpetuates the image of eternal victimhood of LGBTQI+ people, which does not resonate with people’s daily experiences. For some high ranking countries, on the other hand, it in part underestimates that access to justice (i.e. access to legal counsel, litigation, etc.) remains difficult for many LGBTQI+ persons across Europe, particularly those who already find themselves in marginalised positions, such as people from low socio-economic backgrounds, trans and intersex persons, individuals from ethnic or religious minorities, as well as asylum seekers, and persons with disabilities. This aspect is ever more crucial if one takes into account the growing importance that ILGA Europe has paid in the last few years to approaching LGBTQI+ rights from an intersectional perspective. Regrettably, the map does not capture the intersectional dimension of homo-, bi-, intersex- and transphobia across the European continent, and it would be good to consider how these crucial intersections can be addressed in a visual form in order to really give a complex and articulated overview of the lived experiences of LGBTQI+ persons across Europe.

Queer Utopias and Dystopias and the displacement of LGBTQI+ Lived experience

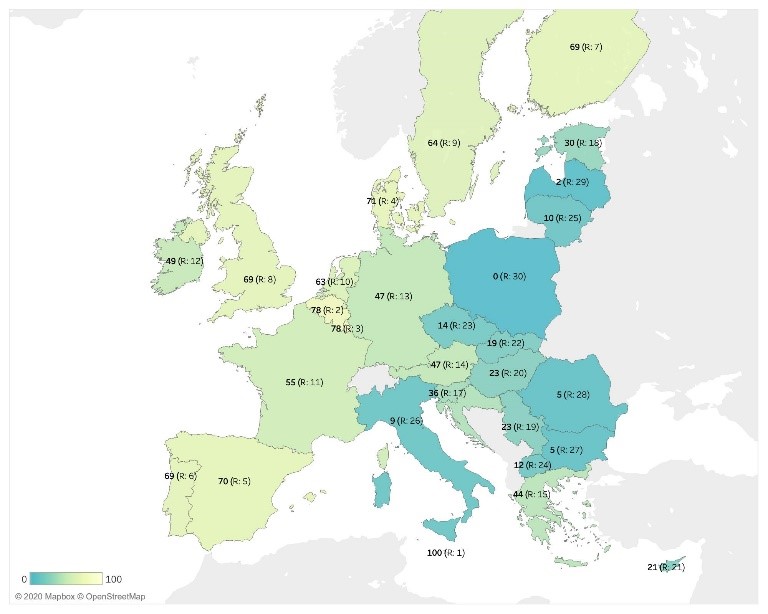

Whereas these arguments often remain within the conceptual arena, the almost simultaneous publication of the ILGA-Europe Rainbow Map and the EU’s Fundamental Rights Agency (FRA) report on the 2019 Survey on LGBTQI+ people lived experiences this year provides us with the unique opportunity to explore and analyse the displacement of lived experiences that occurs when we only focus on legislation to map out LGBTQI+ equality. Due to the geographical spread of the FRA Survey, we can only analyse the data for the EU countries plus North Macedonia, Serbia and the United Kingdom (henceforth EU-plus). Figure 1 provides a redrawn map of the Rainbow Index for the EU-plus countries. Observant readers will note that we have also normalised the index using the min-max normalisation to ease comparison of results throughout the blog post. Finally, although the geographical coverage contains only 30 of the 49 countries of the Rainbow Map, we believe the analysis and comparison of legal equality vs lived experience in those countries will enable us to critically discuss the issues with isolated legal analyses and present a more complex and holistic picture of LGBTQI+ equality in Europe.

Figure 1: Normalised Rainbow Index for EU-plus countries (ranking among covered countries included)

Figure 1: Normalised Rainbow Index for EU-plus countries (ranking among covered countries included)

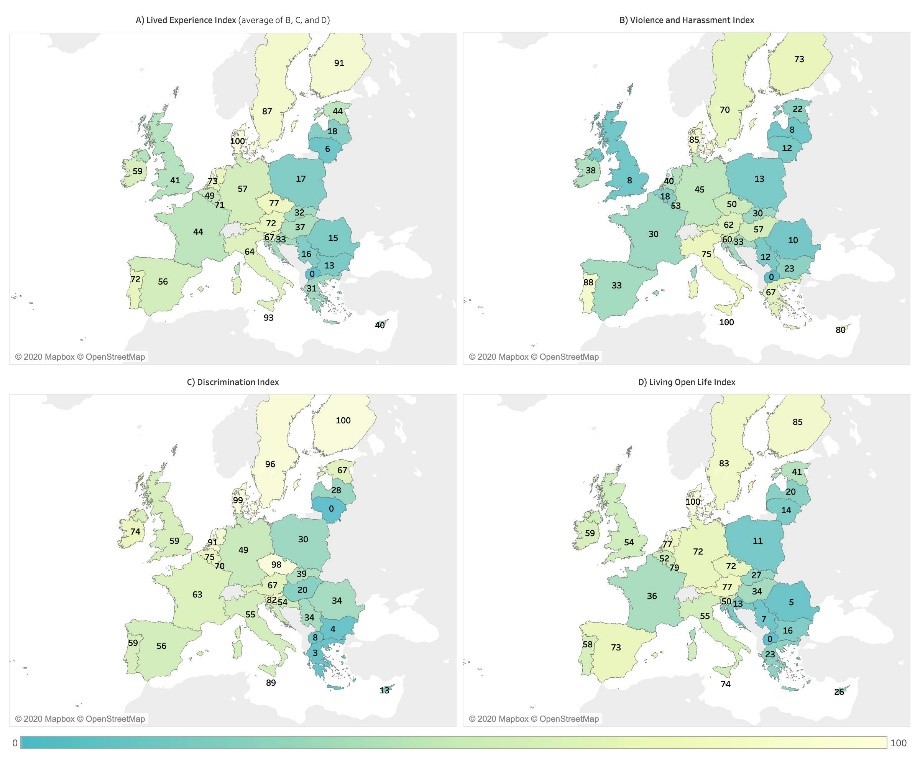

In order to analyse the lived experiences in Europe, we have created a Lived Experience Index (LEI) based on the aggregate level data provided by the FRA survey. This index comprises of a Living an Open Life Index, a Violence and Harassment Index, and a Discrimination Index (for how these have been created see here).

Considering the limitations that the data as publicly made available by ILGA Europe and the FRA present in terms of allowing an intersectional analysis as we previously highlighted, we want to note and stress that we are discussing aggregate measures of experiences of all LGBTQI+ communities. In other words, in our analysis we will focus on the disconnect between the legal frameworks and the lived experiences, whilst pointing out that going forward attention should be paid to the varied experiences of different subgroups, along the identity axes, but also for other intersections. Therefore, we want to remind the reader that, as such, the following maps do not capture the complexity of the experiences of LGBTQI+ individuals in intersectional terms.

With those important caveats in mind, when considering the lived experiences across the EU-plus countries (Figure 2) a complex and multifaceted picture emerges. A first observation we can make is that violence and harassment remain very prevalent across the EU-plus countries, but also that the lived experiences in each country are the result of different combination of experiences of the (in)ability to live an open life, discrimination, and violence and harassment. Consider for example, the United Kingdom. Whereas it scores medium high on the discrimination and the living an open life indices, it scores near the bottom of the violence and harassment index. Thus, whereas the LGBTQI+ communities (on aggregate) might be able to live a relatively open life and remain relatively free from discrimination, violence and harassment seem to be a prevalent feature of their lives. A similar observation can be made for Belgium (a country which ranked second on the ILGA-Europe Rainbow index). The French scores on the Violence and Harassment index confirm the recent statement by the French Government, which admitted that homophobia and transphobia remain deeply rooted within their society. Here, however, it is noteworthy that it is not just violence that remains deeply rooted within French society, but the social climate seems also to reduce the ability for LGBTQI+ people to live their identities openly. At the more difficult spectrum of lived experiences, we notice a complexity of the index. Consider, for example, Greece which scores very low on the discrimination and living an open life index. Its rather high score on Violence and Harassment index seems to indicate that in-person violence might shape LGBTQI+ lived experiences to a lesser extent.

Figure 2: Map of LGBTQI+ Lived Experience Index and sub-indices for EU, North Macedonia, Serbia and United Kingdom

Figure 2: Map of LGBTQI+ Lived Experience Index and sub-indices for EU, North Macedonia, Serbia and United Kingdom

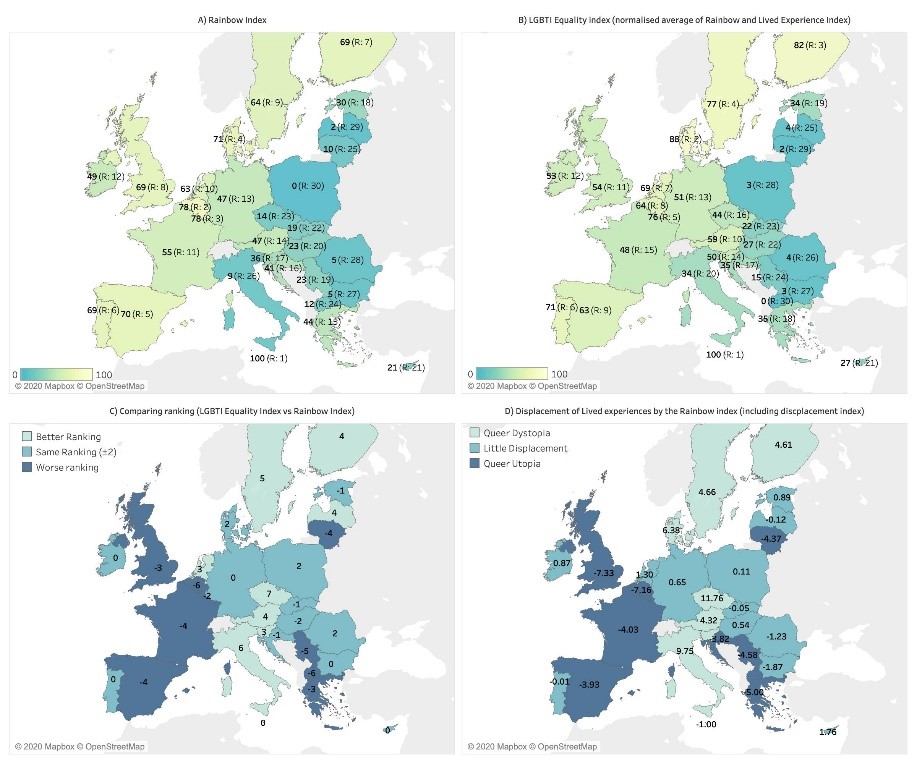

Having mapped out the lived experiences of LGBTQI+ people in the EU-plus countries, we can turn to our main question of how the Rainbow index displaces lived experiences of LGBTQI+ people. As we recognise the importance of legal frameworks, we will compare the Rainbow Index against an LGBTQI+ Equality Index, which is a combination (average) of both the Rainbow Index and the Lived Experience Index. Whilst the differences between the two indices might not be extremely visible when we look at their projections on a map (see panel A and B in Figure 3), the displacement of lived experience by a simple focus on legislation becomes much more apparent when we consider the differences in country rankings (Panel C in Figure 3).

Figure 3: Mapping the displacement of lived experience by the rainbow index for EU-plus countries

Figure 3: Mapping the displacement of lived experience by the rainbow index for EU-plus countries

Considering those countries with an LGBTQI+ Equality Ranking which is at least 2 positions different from the Rainbow Index ranking, we observe quite clearly the need to challenge homonationalist discourse arising from the Rainbow Map. Most notable are Belgium, Spain and the United Kingdom, which respectively rank 2nd, 5th, and 8th on the rainbow index amongst the EU-plus countries, yet only respectively rank 8th, 9th, and 11th when we consider both the law and LGBTQI+ lived experience. On other end of the spectrum, we find that LGBTQI+ Equality in, for example, Czech Republic, and Italy are better than one would expect based on the Rainbow Index.

The displacement of lived experiences is even more pronounced if we considered the relative difference (with average difference as reference) between the two indices. Taking this figure as an indication of the displacement, we can observe countries which the Rainbow Index depicts as some kind of Queer Utopias and Dystopias – places presented as respectively safe and unsafe for LGBTQI+ people, yet lived experience data suggest the opposite to be more likely (for more on how we identify these, see here). Whilst the Utopias in Western Europe are to be expected, we also observe similar trends in Croatia, Greece and Serbia. For those who have been studying LGBTQI+ politics in this region these findings should not be surprising. Take the example of Serbia, where in recent years the government has engaged with strategic changes in the legal and political arena— including appointing an openly Lesbian Prime Minister — to please the EU without working on improving LGBTQI+ lives. In fact, Prime Minister Ana Brnabic has on occasions announced that Serbia is not a homophobic country. Amongst the Queer dystopias are, perhaps not surprisingly, some of the Nordic countries where societies show more acceptance to LGBTQI+ people than the legal framework would suggest. But we also find Italy and Czech Republic with some of the biggest differences between the legal framework and lived realities for LGBTQI+ people.

Although we need much more contextual analysis to understand and explain the complexities in which legal frameworks and lived experiences diverge in each of these countries, what is clear is that the Rainbow Map cannot be read as an indication of LGBTQI+ equality in real terms. Both the presence and absence of law do not always translate to how people experience equality in their daily lives. As such, we caution against the fetishization of legislation within LGBTQI+ activism as well as academia. Furthermore, in light of the existing erosion throughout Europe of the levels of protection of LGBTQI+ rights which has coincided with the rise in popularity of populist governments, it appears obvious that the politics of ‘naming and shaming’ may not be enough in creating long-lasting legislative and social change for LGBTQI+ persons.

Dr Francesca Romana Ammaturo is Senior Lecturer in Sociology and human rights at the University of Roehampton. Her expertise is in the field of LGBTQI issues and human rights, LGBTQI social movements, European human rights and European Citizenship. Francesca’s works is interdisciplinary, versatile and with a strong critical edge. During the last few years, she has been contributing to the field of LGBTQI+ studies by writing on a range of issues, from homonationalist sexual citizenship in Europe to debates on “gestational surrogacy” in Italy. She has published several single-authored articles in several international peer-reviewed journals, as well as authored the monograph titled “European Sexual Citizenship: Human Rights, Bodies, and Identities” for Palgrave in 2017. Dr. Ammaturo has also conducted ethnographic research at the Office of the Commissioner for Human Rights of the Council of Europe. Currently, her research focuses on LGBTQI activism and human rights in Southern Europe.

Dr Francesca Romana Ammaturo is Senior Lecturer in Sociology and human rights at the University of Roehampton. Her expertise is in the field of LGBTQI issues and human rights, LGBTQI social movements, European human rights and European Citizenship. Francesca’s works is interdisciplinary, versatile and with a strong critical edge. During the last few years, she has been contributing to the field of LGBTQI+ studies by writing on a range of issues, from homonationalist sexual citizenship in Europe to debates on “gestational surrogacy” in Italy. She has published several single-authored articles in several international peer-reviewed journals, as well as authored the monograph titled “European Sexual Citizenship: Human Rights, Bodies, and Identities” for Palgrave in 2017. Dr. Ammaturo has also conducted ethnographic research at the Office of the Commissioner for Human Rights of the Council of Europe. Currently, her research focuses on LGBTQI activism and human rights in Southern Europe.

Dr Koen Slootmaeckers is a Lecturer in International Politics at City, University of London. His main expertise relates to sexuality politics in Europe, and in particular the politics that underpin the EU’s promotion of LGBT equality and how this impacts candidate member countries. Koen takes an interdisciplinary approach to his work on the power relations within transnational politics, with an aim to de-construct core-periphery hierarchical relations. Thematically, he is interested in nationalism, masculinities, sexuality politics and the politics of Pride Parades. He has published several articles and is the co-editor of “The EU Enlargement and Gay Politics: The Impact of Eastern Enlargement on Rights, Activism and Prejudice”. He currently working on a book manuscript “Coming In: Sexuality Politics and EU Accession in Serbia” for Manchester University Press.

Dr Koen Slootmaeckers is a Lecturer in International Politics at City, University of London. His main expertise relates to sexuality politics in Europe, and in particular the politics that underpin the EU’s promotion of LGBT equality and how this impacts candidate member countries. Koen takes an interdisciplinary approach to his work on the power relations within transnational politics, with an aim to de-construct core-periphery hierarchical relations. Thematically, he is interested in nationalism, masculinities, sexuality politics and the politics of Pride Parades. He has published several articles and is the co-editor of “The EU Enlargement and Gay Politics: The Impact of Eastern Enlargement on Rights, Activism and Prejudice”. He currently working on a book manuscript “Coming In: Sexuality Politics and EU Accession in Serbia” for Manchester University Press.

Pages: 1 2