by Clare Hemmings

This piece is a part of our Strike Archive, the only content we will be publishing throughout the UCU strike in February and March 2022. In it, we publish teach-outs delivered by our friends and colleagues at the LSE Department of Gender Studies in December 2021, as they withdrew their labour from the LSE in the first week of the strike against casual work, crushing workloads, pay cuts, gender, disability and racial wage gaps and pension cuts. Our archive joins existing initiatives like the LSE Strike Diaries in ‘collective memory making and memory preserving’ of our historic industrial action. As the strike resumes, we stand in solidarity – and ask for yours – with our colleagues at universities across the UK and workers beyond academia, who struggle for better, more equal futures for all.

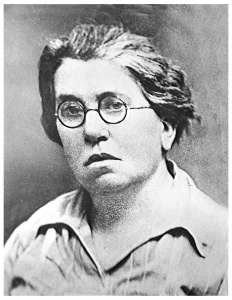

Image credit: Clare Hemmings

Central to this UCU strike are questions of gender inequality, race and class inequality. In the fight to retain pensions worth working a lifetime in the public sector for, we need to remind ourselves and colleagues that pensions are now and always have been enormously gendered.

White men are more likely to have paid into pensions from the start of their careers, are more likely to have been paid higher earnings (and therefore higher employer contributions) over their careers, and remain less likely to need or choose to take periods of care leave (only some of which – care for children – is recognised).

We have already seen that a move from exit to average salary pension calculations affects women, gender and racial minorities most, since they are less likely to end on higher salaries and they are also less likely to move through the promotion levels at the same rate as white men.

So too the attack on what remains of our pensions is a gendered and raced attack, affecting early career members more than others, and making existing precarity likely to resurface at end as well as beginning of working life.

The connections between sexism, gender binaries, racism, poverty, homophobia, and intersecting forms of social abjection have always been central to articulations of revolutionary struggles. Those connections and the brutalities they describe have always been key to challenging authoritarianism within the Left as well as the Right. They are not peripheral to labour rights, but on the contrary are central to any real or effective movement for labour rights, since it is those who are not dominant who are subject to social and political violence and inequality. Attention to these intersecting forms of inequality has never been a cause or site of fragmentation, either, despite what some Leftists may argue. Quite to the contrary: they have been central concerns for socialist, anarchist and social democratic calls for rights since those calls began.[1]

We need a revolutionary feminism to connect these struggles, one whose task and specificity are to connect those multiple forms of aggression, exclusion or abjection. And it must be transnational, in order to make connections with and across revolutionary feminist movements, to learn from mistakes as well as to grow through comparative analysis and deep solidarity. The term ‘revolutionary feminism’ might be familiar to those of you with interests in UK feminism from the ‘Leeds Revolutionary Feminist Group’, whose members worked tirelessly in the 1970s and 80s to combat violence against women and the structure and expectations of heterosexuality.[2] It was an internationally well-known group, but while attentive to sexual and gender-based violence, its members did not then, and still do not now, make the broader analytic or political connections to anti-racism, class-based struggles or the importance of challenging gender binaries that limit all of our lives and embodiments.[3]

As someone deeply staked in queer[4] feminist analysis of multiple, simultaneous sites and modes of authority, and who has researched social movements – particularly anarchism – for many years, I want to claim the name ‘revolutionary feminism’ in its broadest articulation. We need a revolutionary feminism that is brilliant and irreverent enough to make the connections across the multiple sites of struggle that characterise responses to past and present forms of institutional (as well as state) authoritarianism. In this vein, revolutionary feminism insists that social processes are gendered, that labour inequalities are gendered, and that hierarchies of gender underwrite political, religious and cultural life transnationally. Yes indeed (and here I rub shoulders with the radical feminist insistence on the deep misogyny that underlies much of political, institutional and social life). But more importantly, this revolutionary feminism insists that there can be no single-issue gender politics without its own harmful myopias; no deep or lasting account of sexism that does not root that account in an understanding of poverty, of racism, of homophobia and gender binarism: because this is how sexism works. And in this vein too, revolutionary feminism seeks to articulate its priorities as part of a transnational fight to imagine and produce a different world: one that challenges all forms of authoritarianism as linked. In anarchist mode, one can only feed that imagination by refusing the attempts to curb transformative attitude, refusing to isolate issues of power and inequality and refusing to accept the limited terms of community – of life and work – most prominently on offer.

Thankfully, this revolutionary feminist attitude is something that others have already articulated and whose work we can build on. Let me introduce you to three:

Emma Goldman (1869-1940), was born in the Russian Empire (now Lithuania), and migrated to America in the 1880s along with many other Jewish radicals. Her thinking about the importance of women’s emancipation as crucial for revolution (against all the old anarchist men who tried to silence her and stifle her anger) has influenced a century of revolutionary feminists. Goldman argued that marriage and women’s subordination prevent revolutionary attitudes among both them and men, and that without real sexual freedom there can be no social and political transformation. Her commitment to labour struggles included critiques of the control of women’s bodies – through moral sanction as well as legislation – and she championed access to birth control, support of sex workers, as well as everyone’s right to labour and be paid a fair wage.[5] Goldman was no supporter of feminism (which she saw as limited and middle class) but she centred ‘women’s emancipation’ in all areas of political intervention. But first, women would need to free themselves from their inner demons as well as the outer constraints of marriage and monogamy, embracing free love instead. For Goldman then, sex roles and their institutions prevent revolutionary fervour and thus radical transformation will first have to do away ‘with the absurd notion of the dualism of the sexes, or that man and woman represent two antagonistic worlds. Pettiness separates, breadth unites. Let us be broad and big’ (1910, 231), she insisted.

Angela Davis (1944 – present) is a revolutionary black feminist whose work on racial and gender justice in the US spans 5 decades. She was a member of the communist party and the black panthers, and has worked tirelessly as an activist and academic to critique and transform prisons as part of her understanding of the carceral state. Her work in education has been at all levels, and her insistence on the relationship between race, class and gender as the triad of contemporary US subordination is unparalleled.[6] Like Goldman, Davis’s work also tirelessly explores post-revolutionary commitments (in her case civil rights, in Goldman’s, post Russian revolution): to not forget and to deliver on the failed promises as well as achievements of these most potent moments. Davis has written explicitly of the importance of a multi-sited approach to analysis of authoritarianism, arguing (breathlessly and fearlessly) for a feminism that centres ‘a consciousness of capitalism and racism and colonialism and post colonialities and ability and more genders than we can even imagine, and more sexualities than we ever thought we could name”.[7] In Davis’s thinking, then, it is through an intersectional and historical critique that we generate the possibility of imagining a different world (as well as intervening to challenge current inequalities). ‘Revolution is a serious thing’, she reminds us, ‘the most serious thing about a revolutionary life. When one commits oneself to the struggle, it must be for a lifetime.”[8]

Leslie Feinberg (1949 – 2014) was a white working-class Jewish American, most famous for trans* and dyke politics and hir fiction and political writing: Stone Butch Blues (1993) and Transgender Warriors (1997). Feinberg was a committed member of the Workers World Party and an activist for indigenous land rights and self-determination of Palestine (as is Davis). S/he[9] spent hir youth in New York City in anti-war, anti-racist, pro-labour demonstrations and was a journalist and editor for Workers World. S/he refused single-issue politics throughout hir lifetime, and like Goldman and Davis started from the embodied integrity of the incarcerated, the demeaned, the left behind as the basis for a politics of critique and transformation. Hir work centres the relationships among minorities within homeless and poor communities, sex worker, drag and butch-femme communities; hir ability to connect experiences of inequality always started from empathy and imagination. Importantly, the question of gender for Feinberg was a central one that highlighted not only the problem of ‘women’ but of the gender binary itself, connecting that as a form of policing to other aspects of sexism and heteronormativity. The insistence that people be one or the other was for Feinberg another example of the false and empty choices offered by colonial capitalism. Hir focus was on the possibilities for solidarity among the dispossessed as part of a refusal of a recognition politics that separates and demeans:

“I’m not saying we’ll live to see some sort of paradise. But just fighting for change makes you stronger. Not hoping for anything will kill you for sure. Take a chance… You’re already wondering if the world could change. Try imagining a world worth living in, and then ask yourself if that isn’t worth fighting for. You’ve come too far to give up on hope” (from Stone Butch Blues, p.24)

Image credit: Clare Hemmings

So that’s my brief introduction to three people I would like to claim as part of an intersectional and transnational revolutionary feminism! What do these three have in common, other than being rather gorgeous? They were all imprisoned for their politics and desires (Goldman for birth control activism; Davis for participating in revolutionary anti-racist movements; Feinberg for being a ‘gender outlaw’ and desiring beyond heteropatriarchy. They all three take a connected view of oppression and provide a broad account of both critique and transformation. And they all committed themselves to the long game, the struggle for justice over recognition.

Clare Hemmings is Professor of Feminist Theory at the Gender Studies Department, LSE. She works on histories of queer feminist thought, and on the importance of storytelling as part of transforming and working with the pasts we inherit. Her most recent book is Considering Emma Goldman, which works with queer feminist legacies of this anarchist thinker, and which plays with form and content to intervene in her archive. Clare’s teaching is also in queer feminist thinking, and she has recently developed a new course on ‘archival interventions: queer, feminist and decolonial approaches’.

Clare Hemmings is Professor of Feminist Theory at the Gender Studies Department, LSE. She works on histories of queer feminist thought, and on the importance of storytelling as part of transforming and working with the pasts we inherit. Her most recent book is Considering Emma Goldman, which works with queer feminist legacies of this anarchist thinker, and which plays with form and content to intervene in her archive. Clare’s teaching is also in queer feminist thinking, and she has recently developed a new course on ‘archival interventions: queer, feminist and decolonial approaches’.

[1] Christine Stansell challenges this fantasy of a united Left as emerging without attention to gender, sexuality or race, in American Moderns: Bohemian New York and the Creation of a New Century (Princeton University Press, 2000).

[2] See Finn MacKay’s “Reclaiming Revolutionary Feminism” open space piece for Feminist Review for an introduction to some of the people and themes of the group (2014) 106: 95-103.

[3] Sheila Jeffreys was a key founder member of the group; she continues to be vocal in combining feminist critiques of male authority and an insistence of the importance of ‘sex’ as the primary site of women’s oppression (refusing a critique of the gender binary or of the central significance of racism in women’s oppression).

[4] By ‘queer’ I do not mean additional identity marker at the end of LGBT(Q), I mean the anti-assimilationist social movement that was the main space of resistance to the brutality of Western states’ failure to respond to the HIV/AIDs crisis. In that context – the 1980s and early 1990s reclamation of that shaming term as marking the history of experience and the refusal to let it lie – a ‘queer feminist’ approach is one necessarily attentive to the intersections of poverty, racism, sexism, transphobia and homophobia that are central to mechanisms of state, institutional and intersubjective power.

[5] See Emma Goldman’s Anarchism and Other Essays for a blistering collection of these arguments (Mother Earth Press, 1910).

[6] For example in Women, Race and Class (Random House, 1981).

[7] Angela Davis, Freedom is a Constant Struggle (Haymarket, 2016), p. 104.

[8] Angela Davis, in Bart Moore-Gilbert, Gareth Stanton and Willy Maley, eds. Postcolonial Criticism (Routledge, 2014), p.233.

[9] Minnie Bruce Pratt S/He (Alyson Books, 1995) is also the title of a memoir of growing up in the American South, coming out, and living with trans* activist Feinberg.